The extraordinary inner world of Charles R. Saunders, father of Black 'sword and soul'

Those who knew Charles R. Saunders from the outside never would have guessed at the vast universes contained within him.

A big, solid man with a lion's mane of beard and hair, he moved about his Dartmouth, N.S., neighbourhood like a cat, seemingly able to make his earthly frame disappear. One former colleague described Saunders as "the second-quietest journalist I've ever known." Another thought he was dealing with a wizard.

Born in Elizabeth, Pa., in 1946, he earned a psychology degree from Lincoln University. In 1969, the U.S. draft summoned him to fight in Vietnam. Instead, he moved to Canada, living in Toronto and Hamilton before settling in Ottawa for 15 years. In 1985, he moved to Nova Scotia, where he lived for the rest of his life.

He worked as a civil servant and teacher until 1989, when he launched a career in journalism. Saunders died in May at 73, though word of his passing was only made public this month.

In his last years, he lived in a modest apartment on Primrose Street in Dartmouth, without an internet connection, without a landline, without a mobile phone. Once a week, he'd head to the local library and use their computers to catch up with his friends around the world. He lived with little money and told few about his failing health.

People who knew him in Nova Scotia knew his newspaper journalism in the Halifax Daily News and non-fiction books like Black and Bluenose, a profile of contemporary African-Nova Scotian life. He also contributed to The Spirit of Africville in 1992, a landmark book on the destroyed community. Few Canadians knew about his other world.

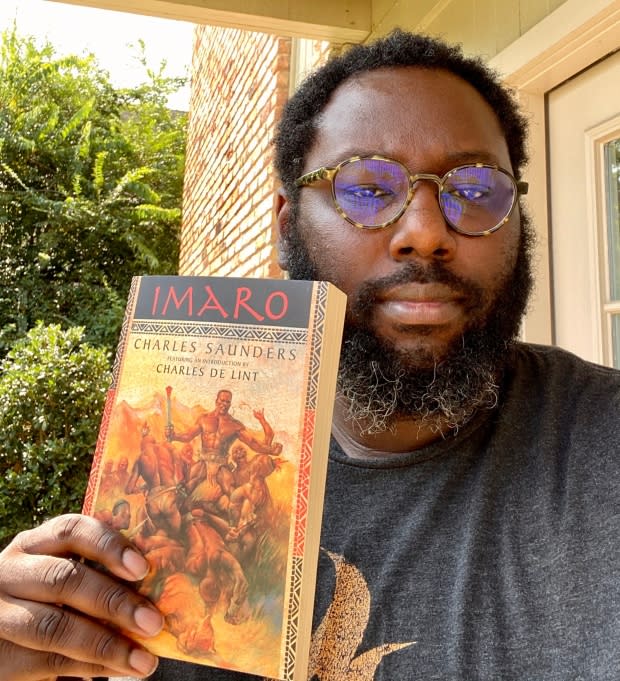

Inside, Saunders was a symphony of swords, beasts, heroes and villains, unfolding an epic adventure of an African warrior named Imaro in a world called Nyumbani, which is Swahili for home. He first thought up the idea for Imaro in 1969 — the year he was drafted — and worked for decades on fantasy novels featuring the character. The first book was published in 1981 and reprinted in the early 2000s.

Troy Wiggins, who lives in Memphis, Tenn., and is the publisher of FIYAH, an American magazine that publishes speculative fiction from Black authors, first read Saunders in the reprinted Imaro books.

"How I describe him is a genius Black man writing sword and sorcery fantasy set in Africa," he told CBC News over the phone from his home. "He's the father of sword and soul."

Wiggins grew up reading and rereading J.R.R. Tolkien and other fantasy classics. But just when he was totally immersed in those worlds, the white writers' underlying racial — and often racist — beliefs wrecked it.

"I stopped reading science fiction and fantasy in high school because I was tired of not seeing Black people," he said. "If Black people or brown people showed up in them at all, we were the antagonist, or the comic relief, or the secondary characters who didn't contribute much to the story. Or we died."

All-Black world

Imaro changed all that. Wiggins could be working away in his day job as a civil servant, but his mind would be in Nyumbani, the West-African inspired setting for Saunders's Imaro books. Everyone was Black: the heroes, the villains, the comic relief and the secondary characters. Wiggins loved it.

"It was a world filled with people who could be my ancestors. I'm an African-American male and I remember feeling vividly the sensory information: how the air smelled, how the people looked, how they were very regal and how they were very human," Wiggins said.

He raced through the epic adventure as Imaro battled demons and beasts, and the dragging doubt that no one could see "that he was a man destined for great things."

Wiggins began to write his own fiction and, feeling bold one day, sent it to Saunders. "He actually read my story and gave me comments. For a fan boy like me that was pretty amazing."

His advice — to reshape a piece of anachronistic technology — turned out to be one of the most popular parts of the published story.

"He had the ability to see through what I was trying to do and give me advice on how to rework it to better serve my story, which is something that great editors do."

George Elliott Clarke helped start journalism career

Saunders began his journalism career in the late 1980s. George Elliott Clarke, the celebrated poet, had written a Halifax Daily News column focused on Black issues, but he had recently moved to Ontario.

He told editor Doug MacKay he should hire Saunders to replace him. Saunders had no background in journalism, but MacKay met him and decided to take a chance. He hired him in 1989.

"Charles was a big, kindly, very gentle man with a huge interest in boxing. And he was a gifted writer. We saw that in a small way in his weekly column at the Daily News," MacKay said from his home in Toronto.

"He did a brilliant job at it. He was covering Black Nova Scotia, in part, but he was also doing a remarkable job of explaining Black Nova Scotian life to predominantly white readers. He was doing in a way what Black Lives Matter has been doing this year in trying to explain the Black experience to white people."

MacKay said Saunders was never afraid to write about tough racial issues dominating the headlines of the day. He knew how to get his message across, MacKay said: "The kind of gift a boxer has: you know when to punch and when not to."

Bill Turpin, another Daily News colleague, said Saunders often also wrote the unsigned editorials. "We would kick around a few ideas until Charles nodded his head and said, 'Yeah. Yeah. I think I could do that.' He never needed more than an hour to submit a beautifully written and logically impeccable editorial."

When the Daily News was shut down in 2008, Saunders retired and seems to have become increasingly isolated.

'His voice is here right now'

On one of his weekly trips to the library, he got a message from a man in Georgia named Milton Davies. Davies is a research and development chemist by day and a publisher and writer of Black sci-fi by night.

He operates MVmedia, which publishes books of "Afrofuturism." He worked with Saunders for many years and together they edited and published Griots: A Sword and Soul Anthology.

He said when Imaro was first published, he was called the Black Conan, drawing comparisons to Robert E. Howard's legendary barbarian. Howard was known as the "father of sword and sorcery."

"Most people would put [Saunders] right up on the same level as Robert E. Howard and there are some people who would argue his work was really above that. His prose was just amazing," Davies said.

Davies thinks The Naama War, the fourth and final book in the Imaro series, was Saunders's finest.

"At this point you shouldn't even be comparing Charles with Robert E. Howard, because he's established his style and his voice, and it really resonates. It blew me away. This is nothing but Charles here. His voice is here right now. Imaro is fully formed."

But like so many people who worked with Saunders, Davies never actually met him in person. "My wife and I travelled to Toronto many years ago and I kind of had a plan that we could go visit him, but I didn't realize how far Toronto was from Nova Scotia," he said with a laugh.

He said Saunders at times dropped out of the loop, but always popped up again. So he didn't worry too much at first when he went silent in the COVID-19 spring. "But we always sent each other birthday cards, because his birthday was a day before mine. And this year I didn't get one from him," he said.

He later learned Saunders's health had been failing for the last year or so. "A lot of people there didn't really know about his fiction. Here it's just the opposite — a lot of us didn't know what he was doing with the newspaper."

Saunders's death was a crushing blow for Taaq Kirksey, who lost a mentor and friend. He's working flat-out to fulfil a promise he made to Saunders when they first started corresponding 16 years ago to develop a television series based on Imaro.

"I told him ... I will make it my life's work to translate your vision to the largest possible audience I can. Charles being Charles, he was agreeable to it," he said in a phone call from his home in Los Angeles.

Like so many authors of Black fantasy, Kirksey grew up devouring the classics — and their often racist undertones. "You are expected to make a rough peace with the racial attitudes of the authors. Charles rectified that at the outset," he said.

Kirksey felt his life changing when he first read Imaro. "Charles reminded me of a wizard," he said. "He kind of worked a certain magic that allowed you to really see and feel and experience the sentiments his characters were feeling or struggling against."

Saunders created "lived-in" worlds where Imaro might slay a supernatural beast, but then have to struggle to keep his marriage together or be a good father to his children.

"It was grown up in a way I had never seen this kind of fiction be. It was clearly wrought from the mind of someone who had lived a full life and it was a response both to things in Charles's own life that might have been missing, and things in the wider culture that were certainly missing. It's just beautiful."

His fantasy worlds were deeply rooted in the human experience, he said. "Being a hero isn't always riding off into the sunset. Sometimes there are real sacrifices, even for saving the world. I've never seen anyone articulate that — and certainly not with a face of colour, a face that looks like mine."

Over 15 years, they worked together over the phone and online. A friendship blossomed. "It was not without its difficulties, because Charles could be so hermetic, so reclusive," he said.

In 2019, he sent Saunders a note that he was coming to visit. He was bringing him paperwork for a television project on Imaro, and a cheque. "It was a triumph for me because I felt I was finally in a place where I could help him financially," he said.

Saunders didn't get the message. Kirksey turned up unannounced at his Primrose Street apartment.

"I practically had to break into the place. I get into the vestibule, rang the bell, no response. Management let me into the building, I knocked on his door, no response. I went around the side — thank God he was on the first floor — and banged on his window. No response," Kirskey said.

He repeated the cycle a few more times. Finally, the door slowly opened, revealing the wizard himself. The two wordsmiths found themselves struck silent. "We didn't say anything. We just smiled at each other and hugged. "

The friends spent a cherished day together. They talked, but mostly it was deeper than words, down in the lower chambers where fiction lives.

Kirksey recently moved his young family across the U.S. to Los Angeles specifically to drive Imaro to completion. "The supervising producer, it's a Black power couple and the pilot script is near completion. The hope is we'll be able to get it sold before the end of the year," he said.

Kirksey said Saunders's death has devastated him and left him struggling to find a way to carry Imaro forward alone. He wanted so badly to be there when Saunders first watched his mythic hero come to life. But Imaro himself had to carry out his own mission after his mother was forced to leave him. Kirksey intends to do the same.

He struggles to understand how Saunders lived a secluded life of apparent poverty on the outside, and of unimaginable wealth on the inside.

"Here was this guy who clearly had this indelible mark, but I got the impression he didn't leave his house much," Kirskey said. "And it begged the question for me, how is he doing all these things? He was a wizard."

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.

MORE TOP STORIES