Facebook request for photo ID angers Leona 'Bugsy' Brown

A Vancouver woman known to friends and family as "Bugsy" has been blocked from Facebook after getting caught in the social media giant's crackdown on users posting under their nicknames.

Leona Brown has been called "Bugsy" since she was a child, and used the name on Facebook for seven years, but was recently blocked from the social network.

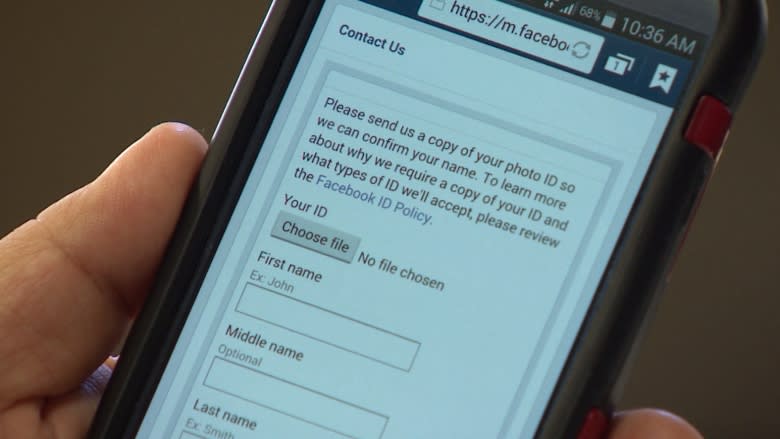

She was told she had provide official identification with her photo ID to "confirm her name" and regain access.

"I feel it's a huge invasion of privacy," said Brown.

"Facebook is a social network. It's not a government database. I shouldn't have to submit ID."

Her identification also doesn't show the nickname "Bugsy," which continues to be used by others on the site.

Facebook requires either government ID or two pieces of other identification. The list of non-government ID it will accept ranges in privacy from a magazine subscription or library card to a credit card or medical record.

Authentic names 'made Facebook special'

Facebook's policy requiring real names isn't new, but the restriction has sparked recent protests from drag queens and others who say they should be able to use "chosen" identities, rather than legal ones.

Last month, the social network also drew heat for flagging Aboriginal names like TallBear and Lone Hill as not "authentic."

In the case of the drag queens, Facebook apologized in a post, but also defended its real-name policy as "what made Facebook special," and something that "protect[s] millions of people every day ... from real harm."

The policy does not require legal names, but the "authentic" ones they use in real life.

Valid concern to submit ID: UBC prof

Anonymous accounts do increase the potential for abuse online, but Facebook could come up with a better solution than requiring photo ID, said a UBC professor who teaches courses on social media.

Rochelle Grayson of UBC Continuing Studies said she can understand why users would object to sharing that personal data with the social networking behemoth.

"Should anything ever come up, Facebook now has that information about them that potentially if required they would need to share," said Grayson.

Grayson suggested, with all the data Facebook collects on users for advertisers, it has options.

"Could they use some of that behavioural insight to flag behaviours that are offensive, as opposed to just names?"

Brown is requesting to regain access to Facebook without sharing her ID, and isn't sure what her next step would be if she's denied.

"Who do we even complain to about a social network that won't give us access?"