The faces of Manitoba's fentanyl crisis

Between January and November of 2016, two dozen people died in Manitoba with opioids in their system, and the total for the year was expected to rise as outstanding toxicology reports are completed.

At least nine of those deaths were confirmed to have involved fentanyl, a powerful opioid that can be 100 times more toxic than morphine. The drug has been linked to deaths across the country and last year, Manitoba's Health Minister Kelvin Goertzen described usage of opioids like fentanyl a crisis.

CBC News has reported on several deaths that involved or are suspected to have involved fentanyl — including its even more toxic relative, carfentanil.

The victims are sons, daughters, parents and friends, and many tried to get help to battle addiction before they died.

CBC News does not know the identity of all the victims, but has spoken to family and friends of several. Here is an outline of who they were.

Aayla Asham, 21

Aatlanta Asham remembers her sister Aayla as a second mother to her growing up while their mother worked several jobs.

"She was a sister, she was a daughter, she was a mother. She was an amazing person," Aatlanta told CBC News in November. "She knew three languages, she knew English, Spanish and French — she was very smart — she wasn't just a drug addict."

When Aayla died at 21 years old in November, she was battling a cocaine addiction her family thought she had nearly beaten. Aatlanta said Aayla had been on several waiting lists for treatment since September.

Aayla was found dead from a suspected fentanyl overdose with two other people in a home on Petriw Bay in Winnipeg, where all three had been renting rooms.

After Aayla's death, Aatlanta said she wanted to see a tougher crackdown on fentanyl dealers and a bigger push from politicians to address addiction to the drug.

"I am not going to let my sister die in vain," she said.

Corey Berens, 35

Corey Berens was 35 years old when he died of a suspected opioid overdose in late September or early October 2016.

"I loved him. Corey was so loved by everybody; everybody is just heartbroken," his sister wrote in an email to CBC at the time.

For friend Reena Leclerc, he will be remembered as "sugar bear."

"I nicknamed him that — every time I see him, I'd call him sugar bear," Leclerc said.

"He's always been so kind, gentle and just a really good friend," she said.

Corey Berens was one of two men found dead in a parked car near a Winnipeg elementary school on Oct. 3, 2016. At the time, police said the bodies had likely been there for days, and suspected an opioid overdose was the cause of death.

Brittney Genaille, 26

Brittney Genaille was the mother to five children, all under age 10, when she died at 26 years old just a few days after police found Berens's body.

Her mother, Cynthia Genaille, described her as a loving mother who was trying hard to get better.

Cynthia told CBC her daughter had been friends with Corey Berens and the other man found in the car a few days earlier. Cynthia said Brittney's friends told family Brittney, Berens and the other man were all getting drugs — usually meth — from the same person.

Her mom believes Brittney was offered either fentanyl or carfentanil while she was doing meth with him. A mutual friend called it "sunshine" in a text message shown to CBC.

After that, people who were there told the family Brittney took "one hoot" of the opioid and collapsed. Paramedics weren't called for two hours, her family said.

Once they called the paramedics, her companions fled the scene and took her cellphone. Cynthia says the alleged supplier told her he threw the phone over the Redwood Bridge because it had too many text messages about drug deals.

He also told Birttney's sister Crystal over Facebook that someone else supplied the opioid, adding "we had both been using meth together!" and nothing more.

After Brittney died, Cynthia told CBC she wanted police to explore manslaughter charges for the supplier, along the lines of ones laid against a dealer in Edmonton following the January 2016 death of Szymon Kalich.

"This needs to be stopped," Cynthia said. "Someone killed my girl. I'll never get her back."

Daneen Cook, 48

Pamela Olson says her cousin Daneen had something special: a way of bringing down her walls and letting Olson — usually the rock amongst her friends — be vulnerable and safe.

"She had a very special spirit," Olson says of Daneen, who was a teacher.

Daneen died at 48 of a fentanyl overdose. She had been battling addiction for years, and to Olson, it often seemed like she was winning. Before she died, Olson says, there were many long periods where she didn't use at all.

Olson didn't know she was using fentanyl before she died. The two have a large family, and Daneen's death has been hard on everybody, Olson said.

"She was a niece, an aunt and a daughter," Olson says. "She was my best friend."

"She wasn't a stereotype," Olson says. "She wasn't what I'm sure some people have an image of in their mind when they think of an addict."

"She struggled with a lot of s--- and she did her best."

Less than a year after Daneen's death on May 24, 2016, her daughter, Ashten Cook, died of an overdose as well. It devastated her father, Robert Warkentin, who described Ashten to CBC News as "joyful," and the "anchor" of her family.

To memorialize Daneen, Olson reached out to friends and family members, who wrote in with detailed, loving memories of the woman they knew as kind, generous, sweet and hard-working.

"I think the most important thing to say is that she was loved, that her addiction took her but she was more than their addiction," wrote one loved one, the daughter of one of Daneen's close friends. "She was helpful and honest. If I wanted to hear truth Daneen was the one to go to for that."

Another pair of women, friends with both Daneen and Ashten, said as a teacher, Daneen dedicated herself to education, and continued to do so in death.

"Part of this is all of us re-committing ourselves to looking after our relatives but also helping others to see that those who struggle with substance abuse could be anyone and we must care for these individuals with patience and commitment; as we would our own relatives. If we don't do this we are enabling exploitation and violence — not stopping it. Daneen was a woman who deserves more than a cheap headline; she was a mother, auntie, cousin, niece, sister, daughter, and — most of all — a beautiful woman who will not be forgotten."

Wesley Elwick, 25

Wesley Elwick was 25 when he was found dead of a suspected fentanyl overdose at a transitional housing facility in Winnipeg, hours after being released following a two-day stay at Health Sciences Centre for a previous overdose.

Wesley was an honour roll student in high school, a talented athlete and a generous man, his parents say. He excelled at everything he tried.

"Whatever he did it would have been fantastic, but unfortunately this was just too big a hill to climb," said his father, Peter Elwick, in December 2016.

Wesley had just completed a 10-day detoxification program at Health Sciences Centre when he left the hospital on October 28, 2016. A few hours later, he was found in the midst of a near-fatal overdose at Portage Place mall. He was revived using the opioid overdose reversing drug naloxone and taken back to the hospital.

Two days after that, he was released again and put in a cab heading to Mainstay, a housing facility run by Main Street Project.

Sometime between 9 p.m. that evening and noon the next day, he overdosed. Police suspected fentanyl.

"It just didn't need to happen," said Wesley's mom, Kelly Hes. "He's 25 years old. He's supposed to be just starting out in life and here he is, he's gone."

After his death, Mainstay started work to develop a new protocol specifically for patrons with addictions issues, dubbed Wesley's Rule.

His parents say they want to see changes to the health-care system so others aren't put in the same position as their son.

"It's only going to get worse. Something has to happen otherwise it's just going to be one tragedy after another," said Peter.

"It's too late for Wesley, but it's not too late if they can change things," said Hes.

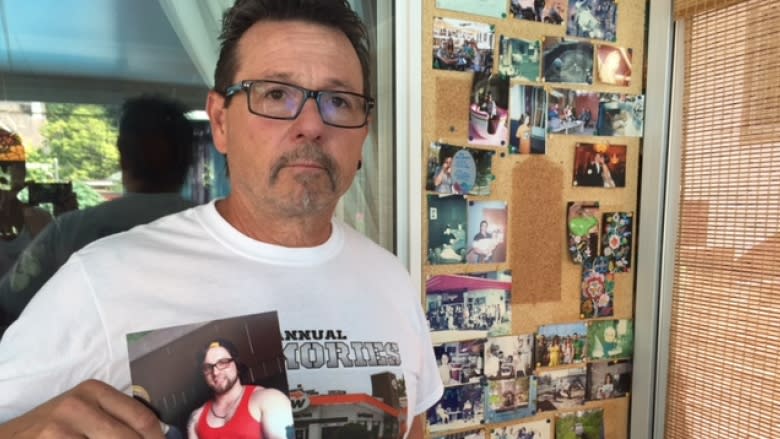

Adam Watson, 27

On Feb. 6, 2016, Adam Watson lost a six-year battle against addiction to fentanyl, becoming the fourth person in his group of friends to die from the drug in two years. He was 27 years old.

At the time, his parents, Lang Watson and Christine Dobbs, described the conversation at the breakfast table one morning when Adam opened up to them about his addiction.

"He started to cry at the table and he said 'I need to tell you something.'"

He had gone from "smoking weed on the riverbank" to using opioids, including fentanyl, his mom said.

Before his death, his parents said Adam tried to quit as many as eight times. The first time, he went to the Health Sciences Centre and was told it would be two weeks before he could get treatment. Medical professionals told him to keep taking street drugs in the meantime to prevent withdrawal symptoms, his dad said.

Over the next six years, Adam went into detox at the Main Street Project once, went to emergency four times and tried methadone several times. Lang said nothing worked.

"In Winnipeg, there is no appropriate help in my view. What's required to detox from opiate addiction is medical supervision. You need medical detox," said Lang.

Jessie Kolb, 24

Jessie Kolb was a power-lifter who loved fishing and his family. His parents, Arlene Last-Kolb and John Kolb, say not a day has gone by since he overdosed on fentanyl in 2014 that they haven't thought of their son.

Arlene and John believe Jessie's struggle with addiction began when he was prescribed Percocet for a weight-lifting injury.

In 2016, Arlene said that before he died, she didn't even know what fentanyl was.

Then one night, during a night out, Jessie overdosed on the opioid. His parents got a call at 1:30 a.m. to go to the hospital, but he was dead by the time they arrived.

"He didn't go out thinking he was going to die," Arlene said.

Since his death, Arlene has teamed up with Christine Dobbs, mother of Adam Watson, to fight for better supports for people battling addiction.

Jessie and Adam both went to Riverview Elementary School and Churchill High School.

With files from CBC's Jill Coubrough, Nelly Gonzalez, Donna Carreiro, Alana Cole, Erin Brohman, Holly Caruk, Leif Larsen and Aidan Geary