Federal security officials approved Winnipeg police efforts to purchase spying devices

Federal public safety officials approved a licence that would enable the Winnipeg Police Service to purchase devices from an undisclosed company designed to intercept the private communications of citizens, documents obtained by CBC News reveal.

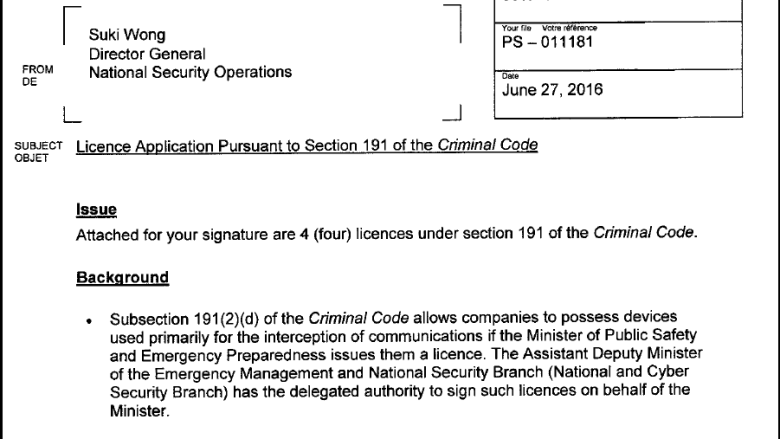

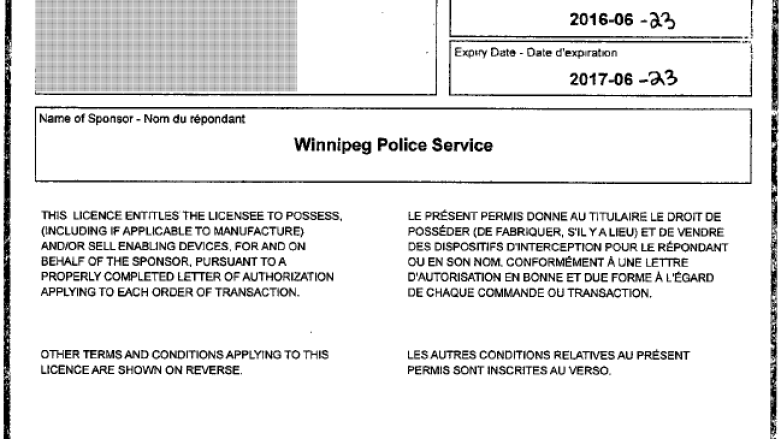

The licence, endorsed by the RCMP's technical investigation division, was approved for a 12-month period by the assistant deputy minister of Public Safety Canada's national security branch on June 23, 2016.

Approvals were also signed for Durham Regional Police, Ontario Provincial Police, RCMP and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, according to the records. The records also showed evidence of 93 occasions dating back to 2008 of licence requests processed by Public Safety Canada.

Unknown device sought

The heavily redacted documents, gathered through freedom of information requests and provided to the CBC by Ottawa-based researcher Ken Rubin, were stripped of identifying information about the manufacturer or the capabilities of the devices.

In recent years, many privacy watchdogs have been critical of the lack of information on the how these tools are regulated. While the licensing documents give few details, they would enable police forces to acquire controversial cellphone wiretapping technologies.

Often referred to as IMSI (international mobile subscriber identity) catchers, these covert tools masquerade as conventional cellular towers, causing mobile phones to transmit signals to the rogue device, rather than directly to towers operated by wireless providers.

However, unlike traditional wiretaps, this technology harvests data indiscriminately, casting a wide net over a specific geographic area, potentially targeting citizens not intended as surveillance targets.

IMSI refers to the unique digital fingerprint of every cellular device. The IDs and the data these devices transmit are what law enforcement agencies harvest for surveillance purposes.

Under Section 191 of the Criminal Code, it is illegal to be in possession of a device used for the "surreptitious interception of private communication" unless used by law enforcement, government agencies or military personnel. In order for manufacturers or sellers of these restricted technologies to lawfully possess them, a special licence must be granted by the Ministry of Public Safety. In order to use these devices to intercept private communications, a justice official must issue a warrant.

In the case of Winnipeg police, an undisclosed company was given authorisation to sell to or operate a device on behalf of the force until June of 2017. This has been the standard process for law enforcement in Canada wishing to acquire these devices for decades — pre-dating the digital era.

Winnipeg police use 'various technologies' to get evidence

Requests for information sent to the Winnipeg Police Service by local media regarding privacy safeguards are typically declined. In this case, Winnipeg police won't comment on whether the service has obtained or intends to obtain devices designed to intercept private communications. A spokesperson said the force would not comment on its investigative methods outside of a courtroom and noted that it does use various technologies to "lawfully obtain evidence."

The Manitoba ombudsman, which investigates complaints about privacy issues and access to information, declined to comment on the privacy issues certain technologies present.

In an emailed statement, ombudsman Charlene Paquin would only say that generally, "surveillance tools are capable of capturing a large volume of personal information of individuals, regardless of whether they are the intended target of the surveillance. This being the case, public bodies should ensure that they are authorized to collect the information and that data retention policies and procedures ensure that personal information is kept only to the extent it is required for the surveillance purpose and is securely destroyed."

'A policeman's dream'

The Criminal Defence Lawyers Association of Manitoba said to their knowledge no defendants in Manitoba have had evidence presented against them that was acquired through the use of these devices.

However, Toronto defense lawyer Alan Gold has had the experience, and said the digital world we live in today is a "policeman's dream."

"Every minute of every day, as we go through our lives we create digital footprints and records of what we're up to and it's very powerful evidence," he said. "When you get a cellphone you're essentially creating self-imposed electronic monitoring on yourself."

Having reviewed documents filed in court by police containing evidence obtained through the use of these technologies, he said he believes that in general judges granting warrants to police understand the risks to privacy.

"Judges are generally fully informed of the apparatus that's going to be used, its capabilities, what the police expect will happen and in general, conditions are imposed to limit the privacy intrusions as much as possible," he said.

Illegal homemade use a concern

Technology and security entrepreneur Michael Legary said IMSI catchers can be operated in a fairly targeted fashion.

"Typically, if it is used in a law enforcement situation, often they know what they're looking for. They're looking for a particular cell phone so when they interact with the cellphones in the area, they can pick out the one they want and then go to a deeper level [and] look at the information inside the communication. So they often have the ability to understand who they're looking for instead of just listening to everyone's traffic," said Legary.

Legary, who spoke to CBC News in general terms due to his ongoing contracts and confidentially agreements in the security industry, cautioned that illegal homemade interception devices built by ill-intentioned people are also a real threat to privacy.

"People out in the real world can have these devices, violating the Criminal Code and that's the concern a lot of folks should have. It's not just law enforcement that has access to these devices," he said.

Privacy in the digital era

What is commonly viewed as a reasonable expectation of privacy as described under Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, is changing in the digital era, said Alan Gold.

"The charter was written, like all search and seizure provisions, in a day and age before our digital world even was dreamed of, but in general this is the constant battle: how do you structure things, so that police have the best chance of obtaining evidence with the least intrusion on innocent people, and that's the eternal question, that's the struggle that goes on," he said.

Ontario Provincial Police declined all comment with regards to their sponsorship of a licence.

Durham Regional Police said that their application was not for one of the devices specifically designed to intercept cellular communications and that the force has no plans to adopt that technology. Spokesperson Dave Selby said they, "would not disclose exactly what item we are seeking, in order to preserve the integrity of an investigation."