Film Review: AFI Fest Closing-Night Film ‘My Psychedelic Love Story’

For at least some of us who lived through the counter-culture/psychedelic era of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Timothy Leary was one of the most annoying or, at least, equivocal figures of a time that hardly lacked for colorful characters. The most famous utterance of this often articulate, madly attention-seeking figure — “Turn on, tune in, drop out” — always seemed utterly idiotic to me and, of the period’s vast drug-addled cast of characters, he always proved the most ubiquitous, reliably on hand for the opening of a bag or the drop of a lude.

However, in his new film My Psychedelic Love Story, the ever-inquisitive and creative Errol Morris has found a way into this eager attention craver that, even if it doesn’t present the man in a new light, does make Leary’s story come alive again in a very particular way. And the portal comes courtesy of one of his innumerable female companions—not one of his five wives, but a typically young, wealthy and hedonistic woman named Joanna Harcourt-Smith, a self-described “psychedelic activist” who, at Morris’ behest, shares her wild ride during a particularly tumultuous time in the late guru’s rollercoaster life.

The driving force that motivates much of Morris’ work is the urge to get to the murky, oft-hidden bottom of things, usually in the realm of politics and, sometimes, how this relates to the family life of those involved. Unusually, his film is based on a memoir, Harcourt-Smith’s Tripping the Bardo with Timothy Leary: My Psychedelic Love Story, which was published in 2013. Sadly, the author died just last week, on October 12, in Santa Fe, NM, where she had lived for some time. She was 74. Originally scheduled to world premiere at the cancelled Telluride Film Festival over Labor Day weekend, it finally debuts Thursday evening as part of the AFI Film Festival and will subsequently be presented on Showtime.

In other hands, this would likely have been a wild but more straightforward story, that of an over-privileged, under-supervised Swiss boarding-school girl who grew up on the Avenue Foch, summered in the South of France, spoke five languages, launched her erotic life at 14, lived with the Rolling Stones (did Daddy know about this?), dated Gunther Sachs, counted Salvador Dali and the Aga Khan as friends and got into all sorts of mischief. But from Morris’ perspective, Joanna becomes a cultural signifier; even if she might not have altered history, she was certainly close by when a lot of interesting things were happening.

“Maybe I was a CIA plant,” she says, teasingly, at the outset. Joanna says she had known Timothy for six weeks when, in January 1973, he was arrested in Afghanistan and finally taken back to the U.S. It was a crazy six weeks. “LSD was calling me. Definitely,” she admits, to the accompaniment of the Moody Blues’ song “Timothy Leary’s Dead.”

It takes a little while to adjust to Joanna as she recalls the wild events of her youth; she beams out to the camera, mostly in a state of great self-amusement, with sparkling eyes and a giant smile on her face virtually the whole time. Is Joanna always like this, or has she spent her decades waiting for this moment when the spotlight would finally shine on her? Is she really this tickled to tell all, to let the world in on what a wild life she once had? Would it please her that, having spilled all these beans, she will not remain unknown but, rather, have her 15 minutes of fame just as she crossed the finish line? Better that than to be forgotten or, as in her case, never really known at all, it should seem. Wherever she is now, she must still be wearing a huge grin. Life was good, and maybe so is the afterlife.

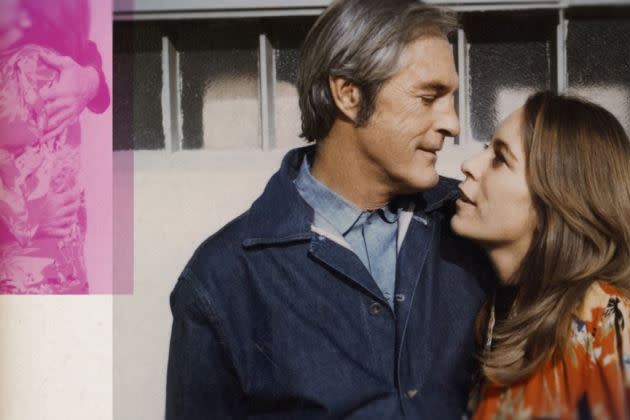

The fabulous and, to a great degree, unfamiliar stock and travelogue footage make their love story look like some hopelessly glamorous movie that should have starred Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn, albeit the stoned and reckless version; it’s St. Moritz one day, Cannes the next, Marbella the following week. Unfortunately, there is a bad guy out there who’s determined to track them down and bring the good times to an end; even more unfortunately, his name is President Richard M. Nixon, who has declared Leary “the most dangerous man in America.”

The heady spree the good-looking couple shares is both exhilarating and so loaded with casually dropped celebrity names that it becomes rather obnoxious; they drop acid every day, Leary relishes his coolness to an unseemly degree, his every move seemingly calculated as a statement of ultimate effrontery, one more dare for the authorities to try to nail him as he stays one step ahead of the goons of all countries. Maybe his ultimate dream would have been to have a movie thriller made about him in which, after eluding all his adversaries on a chase around the world, the final scene shows him leaning back in easy chair outside of Kabul surrounded by fields of opium poppies.

What you see instead are shots of Timothy and Joanna kidding around, cavorting, having a grand time and coming off as quite full of themselves. Maybe the drugs made them feel invulnerable, that the high would never end, that they could find sanctuary and bliss out forever. But Nixon’s long arm grabbed Timothy at last in Kabul, and that was it for his career as an international fugitive and hers as a person of interest, in either sense of the term, until now.

What made the film possible were 10 hours of tapes from Leary and some wonderful archival footage of all the international sites — some genuinely exotic — that the couple traversed, both for fun and as they fled their pursuers from one destination to another. Even when she’s describing quite adverse situations, Joanna conveys a strong sense of adventure; no, things didn’t work out, but it sure was fun while it lasted.

Still, one wonders whether, in her heart, she felt let down or even betrayed by Leary. For him, all his life, women came and went, and there were quite a few more chapters after this. But for Joanna, this was her moment in the limelight; it was a whirlwind, and when it was over, it was all over.

In the end, the film feels both over-extended and lightweight compared to the deep-drill probing Morris has done in his most consequential work; if there are mysteries strewn about, they seem a bit lightweight compared to the meatiest cinematic repasts laid out by Morris in the past. To some of us, Leary has always seemed, first and foremost, an attention-seeker and a publicity hound, so he’d be enormously thankful for Morris’ efforts on behalf of keeping his name and reputation alive and well.

More from Deadline

Showtime Orders Variety Series Featuring 'Desus & Mero' Writer Ziwe

Maura Tierney To Recur On Showtime's Bryan Cranston Limited Legal Drama 'Your Honor'

Best of Deadline

Coronavirus: Movies That Have Halted Or Delayed Production Amid Outbreak

Hong Kong Filmart Postponed Due To Coronavirus Fears; Event Moves Two Weeks Before Toronto

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.