Five hundred years of watchmaking is unveiled in a must-see Oxford exhibition

One of the most important exhibitions of time and timekeeping in recent years debuted this week in Oxford. Named The Heartbeat of the City: 500 Years of Personal Time, the show has been coordinated by The Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA) in collaboration with Vacheron Constantin and Oxford’s History of Science Museum. Following two months in the UK, the exhibition will embark on a world tour – first stop New York City in spring 2021.

According to the exhibition’s co-curators, Roger Michel (founder and executive director of the IDA) and Dr Alexy Karenowska (Fellow of Magdalen College and director of technology of the IDA), the exhibition demonstrates how time, timekeeping and timekeepers are an integral part of humanity. From exploration to war, science and love there is almost always a watch involved, primarily for practical purposes but later they become symbols of why those moments matter.

“The fact that the watches have survived when the people who wore them have (mostly) faded away is a powerful reminder why people strive to do great things and why we celebrate them when we they do,” says Michel. “Watches keep personal time, but they also symbolise the idea of time – with all of its associations.”

In addition to this practical connection to history, there is also a more philosophical relationship between timekeeping and our perception of the past, he says. “An awareness of – even a focus on – the passage of time is a what confers a special aura on ancient objects. Without a sense of the march of time, there is no past, present or future, no sense of trajectory or accretion, no evolution of ideas. In a very real sense, timekeeping breathes meaning into the great monuments that decorate our physical environment.

“Timekeeping makes both memory and aspiration possible by providing the guide posts that we use to map an otherwise free-floating constellation of events that constitute our collective past. It is by dint of our conception of history as having a linear structure – a timeline – that we are able to make sense of the past. Without this linearity imposed by timekeeping, any sense of cause and effect would be destroyed.”

Hence, the timepieces on display have been chosen for their roles in various areas of human achievement, as well as representing the spectrum of crafts and engineering skills involved in watchmaking. The diversity of the pieces on show, as well as the moments in time that they represent are designed to give touchstones to visitors of any age, gender or background, enabling them to find references relevant to their own lives and relationships with time.

As well as choosing pieces from its permanent collection, the IDA approached Vacheron Constantin – the world’s oldest watch manufacture in continuous production – to collaborate on the exhibition. “We believe that Vacheron Constantin represents a good example of a company – and there are certainly others – for which absolute quality is the ultimate goal,” says Michel. “In terms of the human dimension of watchmaking – a dedication to artisanal crafts at the highest level, purity of design, and the value of hand-craftsmanship – none can best Vacheron and there are few companies of any kind that have a greater respect for history and heritage. They are the perfect partner for what we are trying to accomplish.”

For Vacheron Constantin, the chance to get involved with Heartbeat of the City was an opportunity too good to miss. “We were thrilled by the idea of a project celebrating 1,000 years of mechanical horology and 500 years of Swiss watchmaking and we selected 12 timepieces from our private collection to be exhibited," says the brand’s style and heritage director Christian Selmoni, adding that Vacheron’s beliefs mirrored Michel’s idea that a timepiece is more than a device for measuring time, rather it is “an expression of the human conception of time”.

“Initially time was measured through the observation of natural phenomena and celestial objects. It is commonly said that watchmaking is the daughter of astronomy, and that's probably where we find our passion to measure time and its associated functions such as calendar and astronomical complications, chronographs, which allow us to stop time, and chiming complications which are the audible expression of time measurement.”

Also loaning watches for the exhibition is British company Charles Frodsham & Co. Ltd., of which Michel says, “I must reveal that I have a personal affection for Frodsham going right back to the beautiful watches of William Frodsham, Charles’s father. They speak powerfully to my sense of aesthetics, embodying as they do so much craftsmanship just for the joy of the endeavour.”

Richard Stenning, co-director of Frodsham says that the company was keen to be involved from the beginning, loaning a total of eight watches. "We always like to support museums wherever we can," he says. "But this time it was particularly appealing as the exhibition takes a fresh approach to the story of time. It comes from an angle that will make people look at their own watches and how they will become a part of history. You don't need to be an explorer or a movie star, everyone's personal moments in time will affect the future."

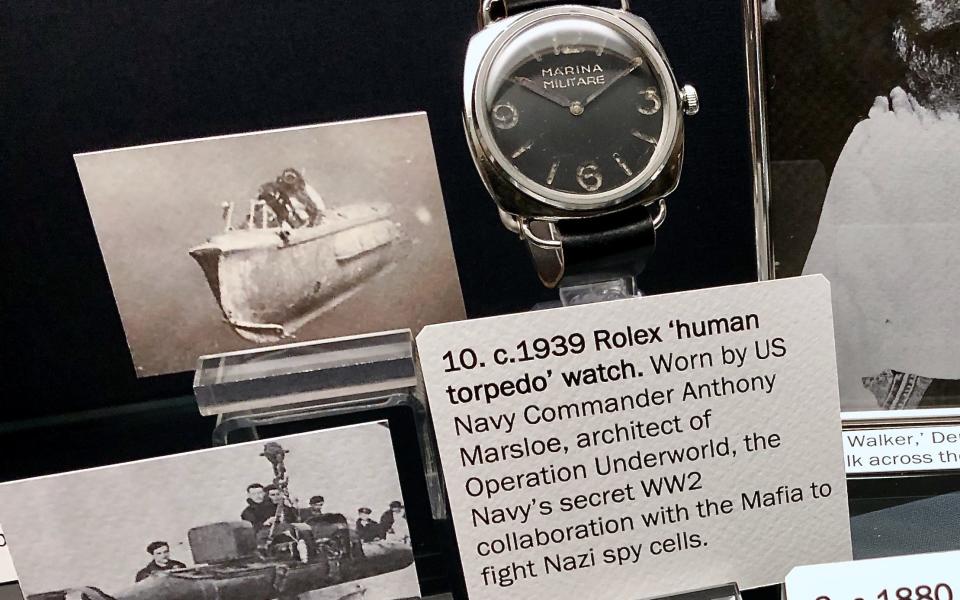

Among the extraordinary pieces on display are George Sutton’s Smiths watch from his 1954 South Georgia expedition, John Vanderwalker’s prototype Certina DS2 worn during the US Navy’s 1960s underwater Tektite mission, an Israeli Defense Forces Tudor Submariner, a Rolex Underwater Commando (“human torpedo”) watch, the Omega Speedmaster wristwatch owned and worn by Australian adventurer Denis Bartell OAM during his solo walk across the Simpson Desert in 1984 and other magnificent pieces by Hamilton, Dent, Patek Philippe, Longines, Universal Geneve, Hafis and LeCoultre.

The Vacheron Constantin watches cover various methods of time measurement and showcase numerous functions and complications, as well as decorative arts. “The selected timepieces not only demonstrate the evolution of watchmaking, but also illustrate how time measurement is linked to the evolution of mankind, from our early aviator's timepiece from 1903, to a World Time pocket watch from 1949 that displays the time of more than 40 cities.”

And, at the centre of the installation is an extraordinary kinetic sculpture created by Michel’s colleague, Oxford University’s Dr Alexy Karenowska, that demonstrates the mechanical intricacies of a lever watch escapement.“The balance [of a watch movement] moves a billion times a year – and does it flawlessly year in and year out. Try opening and closing the door of a Rolls a billion times… Knowing how things work – especially mechanical things – is an essential art of having an enlightened experience of the world. It makes you appreciate humble objects more, encourages you to respect the people who designed them, and points the way to contributions that you yourself might make.”

For visitors, The Heartbeat of the City will provide an opportunity to appreciate the beauty and craftsmanship of the timepieces on display, as well as gain a broader understanding of the mechanics involved in simple watchmaking. But Michel hopes that beyond this it will make people think about how they fit into time and the events that will affect the future, as well as to look at their relationship with artefacts and ponder whether they are an essential tool in enabling both personal and received memories.

And Selmoni agrees: “As the IDA says, ‘at the heart of heritage is time. Without time, there is no past, present or future – no sense of trajectory or accretion, no evolution of ideas, no life.’ This is a great definition of the role of watchmaking as well as our passion to keep on telling time through our creations.”

The Heartbeat of the City: 500 Years of Personal Time University of Oxford History of Science Museum 26 October – 14 December 2020. To visit the Museum, you need to pre-book a free, timed ticket online at hsm.ox.ac.uk; idawatches.org

Sign up for the Telegraph Luxury newsletter for your weekly dose of exquisite taste and expert opinion.