George Floyd's former roommate remembers his friend: 'Every day ... I see his face'

George Floyd was already a "giant" in Alvin Manago's life. Floyd helped him find a job and a place to live, and they ended up being roommates for nearly four years.

Then, two weeks ago, the 46-year-old Floyd was killed after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck during an arrest, sparking international protests over police brutality against Black people.

While Manago is mourning his friend, he takes pride in what Floyd has accomplished in death.

"That's what I'll always remember: 'Big guy, you did it. You're bigger than life. You showed the world,'" Manago told CBC News in a wide-ranging interview, sitting outside the bungalow he and Floyd shared in the Minneapolis suburb of St. Louis Park.

Floyd's funeral took place Tuesday in his hometown of Houston.

His name is still on the mailbox of the house in Minneapolis, and his room is untouched, waiting for his family to claim his belongings. His orange Nike shoes sit by the back door, as though he were going to lace them up and head out to the basketball net in the yard, where he'd often give pointers to a neighbourhood kid.

WATCH | George Floyd's former roommate shares details of his life:

"He was a good guy," said Manago, while acknowledging that Floyd "struggled."

"He tried to be strong. That was his goal — to be better."

Sought a fresh start

Floyd moved to Minneapolis about five years ago, seeking better job opportunities and a fresh start.

He'd been a high school football champion in his hometown of Houston, played college basketball in Florida, then returned to Texas but didn't finish his undergraduate degree.

In the early 2000s, he ran into trouble, with a number of arrests for drugs and theft. He spent four years in prison after a 2007 conviction for armed robbery.

"You know, he was private in his own way," said Manago. "What he had to say was, 'That's behind me, I'm here to do better.'"

Floyd found his way to Minnesota, where he knew friends, and got a job as a security guard at the Conga Latin Bistro. His boss there offered him a house to rent in a leafy suburban neighbourhood.

"You could tell he was comfortable enjoying home, and watching sports on the big-screen TV," Manago said. Moving to Minneapolis "was a chance to get ahead and do better in his life. And he actually was doing it."

Back in Houston, Floyd had a six-year-old daughter named Gianna. Her mother, Roxie Washington, said last week, "I want justice for George, because no matter what anybody thinks, he was good."

He had four other children, including 27-year-old Quincy Mason Floyd, who last week visited the memorial that has sprung up at the site in Minneapolis where Floyd was killed.

Floyd was trying to stitch a life together, holding down a job while paying rent and child support. But when the coronavirus closed the bar, like so many, he lost his work.

Manago said Floyd rarely complained, except for persistent pain in his hip, which he dulled with prescription drugs. An autopsy report after his death on May 25 showed traces of methamphetamine and fentanyl in Floyd's system.

"It was kind of shocking to me, especially meth, because I just never saw this, you know," said Manago.

'Devastated' after mother's death

Manago described a close friendship with his roommate, and said he and his girlfriend supported Floyd when things got tough, especially two years ago, when Floyd's mother, Cissy, died.

"When he lost his mom, he was devastated," recalled Manago. "My girlfriend, Teresa Scott, she always would make sure he ate, because he was in a slump. He just stayed in his room, reading the Bible aloud to himself."

On the night of May 25, while he was pinned to the pavement by police, Floyd called out to his mother. In his eulogy during the memorial service in Minneapolis last Thursday, Rev. Al Sharpton recalled that moment.

"At the point he was dying, his mother was stretching her hand out, saying, 'C'mon, George, I will welcome you where the wicked will cease from troubling,'" Sharpton said. "'There's a place where the police won't put knees on you, George. There's a place where prosecutors won't drag their feet.'"

'Every day ... I see his face'

Manago said he learned about Floyd's death early in the morning on May 26, when he got a knock on the door. A reporter asked if he knew Floyd, then showed Manago a blurry video of police kneeling on his friend.

"I didn't want to believe it was him, and the more I saw it, the more it broke my heart," Manago said, his eyes tearing up at the memory.

"It was savage and brutal, and I just couldn't believe that a human could do that to another, like he was enjoying it," Manago said angrily.

He said that it was already such a tough time, with everyone doing their part to contain the coronavirus. "Then, to see that individual do an act of cruelty like that, during a time [where] we all should come together — it was devastating."

Neighbours on the street have filled Floyd's former home with flowers. A GoFundMe campaign started in the community will help Manago pay Floyd's share of the rent for the next few months.

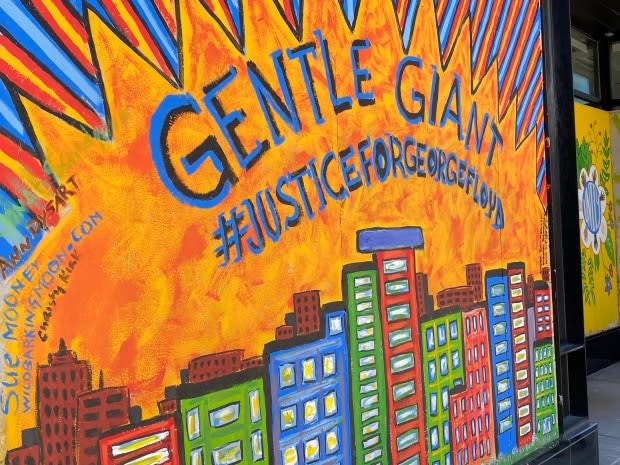

Floyd's face is now everywhere, on television and social media and in street art all over the world, and his name is on people's lips as part of the larger cause of police accountability. But for Manago, it's more personal.

"Every day, you know, I see his face. I go in his room and look at his shoes and know Floyd's not coming home. And, you know, I'm going to miss him."