Getting Back to 'Get Back': The Long and Winding Saga of Glyn Johns' Lost Beatles Album

Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd.

Glyn Johns was relaxing at his London home one night in December 1968 when the phone rang. It was Paul McCartney. Johns told him to f— off.

In his defense, he assumed he was being pranked by another member of the British rock aristocracy. "I thought it was Mick Jagger trying to be amusing," Johns tells PEOPLE. "I can't remember exactly what I said to what I thought was Mick, but it was more or less, "F— off, what do you want?' And, in fact, it was Paul."

At just 26, Johns already had an illustrious career as a first-call studio engineer, guiding sessions for some of Britain's biggest bands, including the Pretty Things, Small Faces, and Spooky Tooth. Most famously, he'd worked with the Rolling Stones on a string of classic albums, including their then-current smash, Beggar's Banquet. Hence why a late-night joke from Jagger wasn't outside the realm of possibility. But a cold call from one of the Beatles was a little more unusual.

Johns listened as McCartney outlined the Beatles' upcoming project: a live album of all-new songs. It was to be the band's first public concert in over two years. To mark the occasion, a film crew would document the proceedings for a proposed television special tie-in. Johns' credentials made him uniquely suited to assist them with this ambitious multimedia venture, stepping into the role traditionally filled by their producer, George Martin. He'd previously engineered several live albums and also handled sound for The Rolling Stones' Rock 'n' Roll Circus concert film, which featured performances from John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Given the Beatles' close ties with the Stones, it was only natural for Johns' name to come up during pre-production.

"Paul very politely told me what his plan was and asked if I would be interested in doing it," says Johns. "And I went, 'Absolutely, yeah! Great.' So he said, 'Well, we're going to start rehearsing just after New Years and I would really appreciate it if you'd come to all the rehearsals.' I said, 'Sure, okay.' And off we went."

So began a long and winding saga that's lasted for over half a century. Johns was instrumental in the creation of the Beatles' swansong, Let It Be, but the majority of his contributions stayed locked in the vault. Now, with the arrival of the expansive new Let It Be box set, his initial version of the record — more true to the spirit of the Beatles' original concept and hailed by many as superior to the official release — is finally available for all to hear. Composed of different mixes, different takes and even different tracks, it's tantamount to the discovery of a long-lost Beatles album.

Michael Putland/Getty Images

Despite his roster of high-profile clients, Johns had barely crossed paths with any of the Fabs when he first showed up to work on Jan. 2, 1969. Aside from The Rock 'n' Roll Circus, his only real Beatle encounter occurred when Lennon and McCartney dropped by a Stones session to lend their voices to the group's single "We Love You" in the summer of 1967. "I was just the engineer, and they were in and out," Johns explains. "It wasn't like they hung out for a day or something. So I didn't have any relationship with either of them."

Even so, the Beatles immediately embraced this relative stranger in their midst. "All of them were unbelievably welcoming," says Johns. "They made me feel so comfortable. From the minute I walked in the door, [Beatles' roadie] Mal Evans greeted me and was lovely. Then, when each member of the band arrived, it was as if we'd been working together for ages, almost. They were very collaborative indeed. They made me feel very comfortable."

Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd.

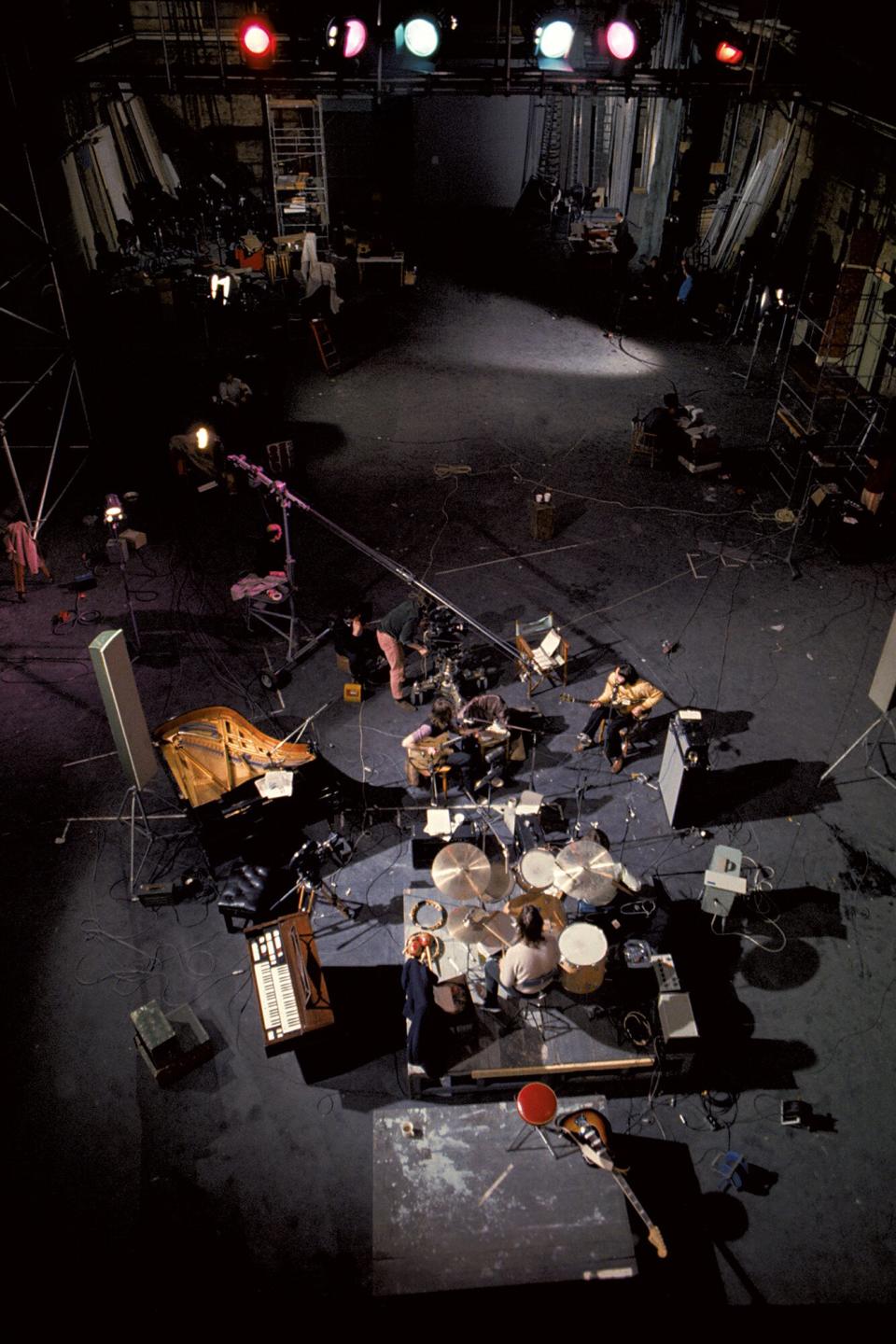

The physical accommodations, on the other hand, were slightly less comfortable. They spent their first week of rehearsals in a drab and drafty soundstage at Twickenham film studios on the outskirts of London. To Johns, playing in the warehouse-sized room was akin to playing a game of ping pong in the middle of a football stadium. Even under these unusual circumstances, the Beatles retained their discipline and enthusiasm. "It was a bit odd, but it worked okay. We just got on with it, really," Johns says. "My whole experience with the Beatles was really no different from any other band, except it was the Beatles. There was nothing unusual about their behavior or their work ethic or anything else. They were exactly like any other band that I had worked with, in that regard. They jammed, just like anybody would. If everyone was in a good mood and having a good time, they would mess about."

But good times weren't always forthcoming. Johns had unwittingly entered the Beatles' orbit during the most troubled time in their history. The project's working title of Get Back was more than just the name of a new McCartney song but also a mission statement. The Beatles —and McCartney in particular— yearned for a simpler era before business pressures and private psychodramas threatened to erode their core friendship. A return to the stage would mean a return to being a band, rather than four distinct studio artistes with increasingly different ideas of what, when and how to play. The live album would be the antithesis of their increasingly elaborate studio productions like Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and The White Album, both of which took months to complete and exhausted the Beatles' collective goodwill. Instead, Get Back would be spontaneous and exciting, a reminder of everything they had originally loved about rock 'n' roll.

That was the theory, at least. Not all of the band believed in this Gatsby-esque premise, and the early rehearsals failed to have a unifying effect. Yoko Ono often gets the blame due to her constant presence (at Lennon's urging). Though her attendance undoubtedly disrupted the delicate interpersonal dynamic, many factors lead to their dissatisfaction. These ranged from Lennon's substance abuse issues, Harrison's growing frustration with his second class status in the band, the intrusion of the documentary film cameras, the cold, damp atmosphere of the soundstage, and even the early morning call times.

Disney+ John Lennon and George Harrison

Matters came to a head just after lunch on Jan. 10, when Harrison withdrew from the rehearsals and temporarily quit the group. Though he was coaxed back into the fold days later, the moment has gone down in Beatle lore as "the beginning of the end" of the band. Yet Johns maintains that the incident has been exaggerated in its retelling over the years. "It was disappointing, but they'd been together a long time," he says. "They had an argument and they made up, just like anybody else. If people work in an office for a few years, there are going to be falling-outs. This was the same s—. I've worked with lots of bands that have had arguments in the studio and somebody's gone off in a tiff and then they came back again. But because it was the Beatles, everybody made this huge bloody great issue out of it and turned it into the end of the world. But it wasn't."

Harrison's return came with some conditions. Plans for a televised comeback concert were abandoned, as were the rehearsals at Twickenham. Instead, Harrison insisted they decamp to their newly constructed studio in the basement of the Beatles' Apple Records headquarters at 3 Savile Row in London's West End. The atmosphere was certainly nicer than the cavernous soundstage, but there was one problem: the sound equipment was a mess. The facility had been designed by "Magic" Alex Mardas, a self-proclaimed electronics wizard and notorious wheeler-dealer who had supposedly charmed the Beatles with tales of his dubious inventions: a voice-activated typewriter, color-changing paint, a force-field for McCartney's house, video phones, a robotic housewife, wallpaper that acted as stereo speakers, and even an artificial sun. At one point he managed to convince Lennon and Harrison to donate the V-12 engines from their sports cars so he could construct a flying saucer. It didn't work — and neither did the recording studio.

Johns was sent to scope out the fresh facilities with Harrison. Instead of a state-of-the-art studio, he found pure chaos. "It was the most absurd and ridiculous thing I've ever seen," he says with a chuckle. "I mean, I knew immediately the guy didn't have a clue what he was doing. He was a TV repairman! That's how he started, but he fooled everyone into thinking he was some kind of genius. Well, he wasn't. I walked in and there was a console in the control room that looked like something out of Buck Rogers. And there were eight speakers on the wall, all the size of a ham sandwich. Because it was eight-track recording, he thought you had to have eight speakers. The guy didn't have a f—ing clue. So I burst out laughing and George Harrison wasn't terribly happy with that. He got a bit miffed."

Rental equipment was hastily installed and soon they settled into what effectively became the Beatles' private clubhouse. They were joined by old friend Billy Preston on keyboards, and almost immediately there was a significant boost in morale. "This was their office building, so it was home for them," says Johns. "They were very much in control of what was going on. It worked really, really well." The music was strong, even if the direction of the Get Back venture was uncertain. With a public concert now out of the question, the notion of a traditional live album went out the window. Johns had been tasked with recording the rehearsals, primarily as a reference for the Beatles to listen back and develop their arrangements. Though they were unsure whether they were rehearsing, making a record, or simply workshopping, the band played on. Relieved of the pressure of having to produce a formal "Beatles Album," they let down their hair and enjoyed themselves.

Johns found himself in the unique position of witnessing a new collection of Beatles' material taking shape around him, and the raw creativity left him exhilarated. Inspired by the raucous energy, he had a thought: why not let listeners in on the fun? He conceived of a new kind of album, midway between a studio endeavor and a live record; a "fly-on-the-wall" audio documentary that portrayed the Beatles as a band at work. "I wanted to show what a good time we were having, really," he says of the novel approach.

It was an appropriately meta premise. The Fabs had been instrumental in elevating rock albums to the level of an art form. Now they could deconstruct their reputation with a project that illustrated the songwriting process — the perfect postmodern record. "Having proved to the world they'd rewritten the rules concerning music produced in the studio, I thought it was great to have them stripped down, to show who and what they really were as a band," Johns continues. "I'd been able to witness that, having been in a room with them, and I was blown away by the whole experience. I thought it would be great to put it on record."

Disney+ Glyn Johns (far left) with Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and George Harrison in the control room of Apple Studios, January 1969.

Johns edited together highlights from recent sessions as a proof of concept, incorporating banter and false starts among the full songs. He presented this rough demo to each of the Beatles for consideration. It was unanimously rejected. "It wasn't that they didn't enjoy it. It was just that they didn't see it as being what they were trying to achieve," he says. "To be honest, I didn't expect them to go, 'Oh, what a great idea,' but I thought I'd run it by them just in case. It was an option, if you like."

A more immediate concern was how to craft an end to the documentary in progress. With Ringo Starr due to shoot a feature film in less than two weeks, the deadline was fast approaching. "We were in the middle of doing something that had gone incredibly well musically to that point," says Johns, "but our film was being made about a concert that wasn't going to happen anymore. So it was a bit of a predicament, really."

The solution arrived one day when the group broke for lunch. "Ringo was sitting next to me," Johns recalls. "We were on the top floor of the [Beatles' office] building and he said, 'Have you ever been up on the roof here?' And I said no. He said, 'It's incredible. You can see the whole of the West End of London from the roof. Come on, I'll show you!' I honestly don't remember whether it was my idea or his, but from that visit to the roof, the two of us came up with the idea of possibly playing up there."

Disney+

They put it to the others, who mulled it over. The suggestion had much to recommend itself. It was technically a live concert, but without the hassle of hysterical fans and security. Plus, the idea of blasting rock 'n' roll throughout the staid side-street, populated mostly by snobbish tailors, appealed to their sense of rebellion. And perhaps most importantly, very little effort was required of them. All they had to do was go upstairs. Thanks in large part to laziness, the climax of the documentary was in place.

On the afternoon of Jan. 30, 1969, the Beatles climbed five flights to the top of Apple Records headquarters and played nine songs (or five titles) over the course of 42 minutes. Scaffolding planks had been laid to support the weight of the gear, and the sensitive guitar and drum mics were sheathed in women's pantyhose to guard against the gusts of wind. Other than that, few concessions were made. "Recording in the open air was a complete doddle," says Johns. "The biggest problem was the temperature!" To ward off the winter chill, both Lennon and Starr wore their ladies' coats, and a staffer held a steady stream of cigarettes to warm their fingers. It was arguably the most unusual concert of the Beatles career — and also their last.

The sessions for what was still known as Get Back wrapped the following day, on Jan. 31. The tapes gathered dust until that spring, when Johns got another call from Paul McCartney. "He asked me to meet him and John at Abbey Road [Studios]. They said, 'Do you remember the idea that you had while we were doing Get Back?' And I said yes. And they said, 'We'd like you to go away and do it.' All the tapes were on the floor in the control room — piles of tapes! I went, 'Okay, when do we start?' They said, 'Well, we're not going to be there. It was your idea. You go and do it.' At first I thought 'Blimey, that's marvelous.' But in the car on the way home and I suddenly realized, 'Hold on a minute. They've obviously lost interest in this completely. They don't think I'm marvelous, they just don't give a s—!'"

He assembled a tracklist in the same style as the demo he made during the sessions, blending new material with works in progress, studio chatter, loose jams and incomplete covers of old R&B chestnuts like Jimmy McCracklin's "The Walk" and "Save the Last Dance For Me" by the Drifters. The final mix was submitted to the Beatles in May 1969, weeks after the "Get Back" single hit the shelves. Johns' album seemed poised to follow in July. Cover art was designed, which telegraphed the "back to our roots" ethos of the project by mimicking the sleeve of their debut record Please Please Me, released six years (and several lifetimes) earlier.

Parlophone

But then came a complicated series of snags and delays. Officially, it was decided that the record should be released alongside the documentary film, which required many more months of editing. Unofficially, Johns' suspicions were correct and the band were losing interest in the project. In the meantime, they busied themselves by recording a new album. Johns assisted on the initial sessions, but as it became clear that this was going to be a traditional studio production, the Beatles returned to familiar territory at Abbey Road and welcomed back producer George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick and Phil McDonald, the team behind some of their most daring soundscapes. The sessions marked something of a homecoming, and the resulting record — which would prove to be their last — was named for their longtime creative laboratory. "Abbey Road was a fantastic record," says Johns. "And I'm really glad that they went back to George Martin, because he and Geoff did the most brilliant job. It was a much better record because they finished it, I can assure you."

By the dawn of 1970, the Beatles existed in name only. Lennon had privately informed his bandmates of his intent to leave the group just before Abbey Road was released September, but there was still the not-insignificant issue of finishing Get Back, which had been retitled Let It Be to distinguish it from the now months-old single. Johns revisited the tapes a final time that January, with its tracklist altered to align with the almost complete film. Coming on the heels of the highly polished Abbey Road, the band began to have second thoughts about their unvarnished "warts and all" experiment. "Having made Abbey Road as beautiful a record as it was, there was obviously some disagreement about [the direction for] Let It Be," says Johns. "I'm reading between the lines here, but I can only assume that John wasn't really happy with what I'd done or that idea."

And there was also a matter of credit. Johns' had been brought on as an engineer, yet his work far exceeded the job description. Hoping to remedy this, he asked if he could be credited as producer, near the top of the studio hierarchy. "I didn't want any royalties, I just wanted credit," he explains. "Because at that point it would've done my CV good. And everybody was quite happy about that, except for John. He couldn't understand why I didn't want any money! I said, 'Listen, you could release the four of you singing the phonebook and it would sell a huge number of records, no matter who did what. So I don't think I deserve any financial recompense, but a credit would be quite handy.' But it didn't come to pass. John wasn't unpleasant, he was just quizzical. But I didn't take any offense."

In the end, it was a moot point. Lennon ultimately rejected Johns' efforts and enlisted the services of Phil Spector, the autocratic audio auteur who produced Lennon's recent solo single, "Instant Karma," in early 1970. "John obviously had a conversation with Spector and thought it would be a great idea to give him what we'd recorded and have Spector crap all over it," Johns reflects. Hiring a maximalist like Spector, the architect of the bombastic "Wall of Sound" production technique, seemed to completely contradict the original premise of the project and struck many as an act of sabotage. Paul McCartney was so outraged by the unauthorized orchestral additions to his track "The Long and Winding Road" that he cited it at the legal proceedings to formally dissolve the Beatles at the end of the year. Johns was similarly aggrieved. "I was extremely disappointed when I heard the Phil Spector version, which was disgusting." (The word "puke" often crops up in his description, though not during this discussion.) Spector's Let It Be was issued on May 8, 1970, just weeks after the Beatles publicly announced their breakup. "And my mixes ended up on a shelf in the basement of Abbey Road," says Johns.

That's not entirely accurate. Johns' Get Back mix earned a sort of infamy as one of rock's first major bootlegs. An acetate was leaked to a reporter in September 1969 (supposedly by John Lennon, of all people) and quickly spread throughout the counterculture underground. Radio stations in Boston, Buffalo and Cleveland broadcast the demo in its entirety, creating a golden opportunity for illicit tapers to record it off the airwaves. Dubbed Kum Back, the illegitimate release was ubiquitous enough to earn a review in Rolling Stone. But aside from these poor quality bootlegs — and a handful of tracks included on the Beatles Anthology in 1996 — the original incarnation of Get Back/Let It Be remained locked away.

Johns, meanwhile, moved on. "I sort of forgot about it. I'm busy, y'know what I mean," he laughs. That's putting it mildly. He spent much of the '70s defining the sound of the decade. His list of clients reads like a complete history of classic rock: Led Zeppelin, the Who, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Eric Clapton, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Joe Cocker, the Eagles, Faces, Leon Russell, and the Clash, to name but a few. More than perhaps anyone in music, Johns can truly say that his time with the Beatles was just another gig.

Mike Coppola/Getty Images

Today, Johns is 79. He was 26 when he recorded Get Back. Does he feel a sense of closure now that this half-century saga is complete? Not quite. "I'm not overly concerned with it at this point in my life, but I guess it's okay," he says with trademark understatement. "It's pretty good."