'Girls' keep working streets despite serial predator warning

Chantelle walks the same streets her sister used to walk, head held high, determined to turn another $20 trick, then kick her crack addiction and figure out how to get a roof over her head.

Determined as well, on this July night, to never forget her sister Edna Bernard - a mother of six who was strangled, lit on fire, then dumped in a farmer's field near Leduc in 2002.

Her sister's remains were among five bodies found since that year within an eight-kilometre radius, something that last week prompted the RCMP to say they're looking for a "serial predator." Police identified the other victims as Katie Ballantyne, Delores Brower, Amber Tuccaro and Corrie Ottenbreit, the latter the most recent to be discovered after disappearing in 2004.

- The case of Katie Sylvia Ballantyne

Chantelle doesn't want her real name to be used. But the threat of a serial predator — and the haunting memory of her sister's death — haven't deterred her from what she calls "self-employment" along Edmonton's 107th Avenue, a street dotted with ethnic shops, restaurants and payday loan businesses.

"I'm not scared of what's going to happen," says Chantelle, her brown hair tied back with elastics and brightly coloured plastic barrettes. "Life goes on, right, for a little bitty while."

Her dark eyes dart back and forth as she speaks. Her body, fuelled by crack, seems constantly in motion.

"Because why should it scare me?" she asks. "We all live once, but still I'm not scared and I'll fight my way out."

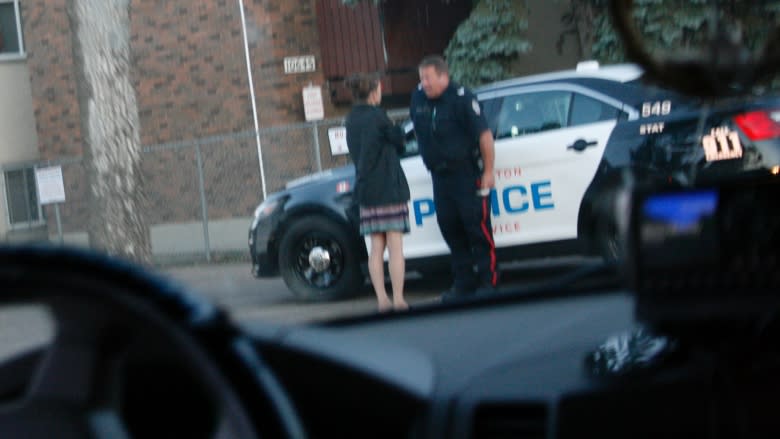

Those who do fight their way out often find themselves in the back of Kari Thomason's Jeep. She's a social worker with Metis child and family services.

When Chantelle sees the vehicle and recognizes Thomason, she runs to the Jeep and leans in to give her a hug, grabbing handfuls of candy, a snack and a bottle of water. As she runs her backpack spills open, and a beer hidden under a brown towel spills onto the street.

Chantelle is one of Thomason's "girls." They're the women Thomason visits as she "runs track," as she calls it, as part of her work as a coordinator with Project SNUG, an organization which helps sex trade workers leave street life.

"They'd rather see a cop than me," jokes Thomason, as she spots a girl she hasn't seen in some time across three lanes of traffic, riding a bicycle.

The loop along 107th Avenue, Stony Plain Road and 118th Avenue is often the first place Thomason visits after returning from vacation. Sometimes she has one of her own children in tow, helping her write down the familiar names of the women standing on the street corners.

"There are some girls who we honestly did not think would make it as long as they have, and they've proved us wrong, thankfully."

Like the girl who keeps stealing from her "dates," robbing them before running off. She's nearly died twice, says Thomason.

"It's like, holy man, you have more than nine lives," Thomason says. "And yet that isn't enough for her to stop because of her mental health state and because of what she endured right from a baby, literally, and she knows nothing other than this world of being involved in the (sex) game.

"She'll tell you .... ' there's nothing (else) I can do.' "

'You just never know who is next,' says Thomason

CBC's Aboriginal Unit has revealed there are at least 15 unsolved cases of indigenous women who vanished or were murdered in and around the Edmonton area.

While the discovery of the remains of the five women near Leduc looms large on Edmonton city streets, it barely resonates with some of the women Thomason stops to speak with. They're used to threats, black eyes, broken bones.

For Thomason, though, the prospect of a serial predator makes her fearful for the safety of these street women.

Her life's passion is on the city streets, delivering blankets, cans of soup, driving women to medical appointments, listening to their concerns. She's spent almost two decades tracking them, and has known personally many who have been murdered, like Ottenbreit.

"She was a kind gal," Thomason recalls. " She never got to do a lot of things she wanted to do, she felt cornered and unsafe."

Thomason stops to scan the streets for two girls she's looking for this night. She knows there may come a day when their names join Ottenbreit's and the other victims.

"It's a raw feeling and you just don't want it to be true, because then you know that they're gone, they're truly actually gone," Thomason says. "I get sickened by it, you just never know who is next or how many other ones are going to be found out there."

The women who live trick to trick know they're a possible target. They are sometimes forced to dart behind buildings when they recognize a bad date coming, eking out a precarious existence where addiction and abuse are constant threats.

Despite bravado like Chantelle's, Thomason says fear is a constant for many sex trade workers. "For most they're scared, most of them have fear of the unknown, right, and what (might happen) if I get into that guy's vehicle?"

Still, they keep climbing in — the rush of adrenaline or the next crack hit pushing them on.

Like Ann, 57, who since her mother died a decade ago, has built make-shift shelters near 118th Avenue, scavenging back alleys for clothing and scraps of cardboard and plywood.

Despite that, she maintains a kind of beauty, with coiffed hair, a teal blue tube top altered from a little girl's discarded tutu, and a black scarf stylishly slung over her shoulders.

"Oh I need condoms, got condoms?" she asks immediately when Thomason's Jeep pulls up in front of Ann's latest 'house,' a yellow milk crate with a slab of cardboard as a seat.

She chats with Thomason like old friends getting together over coffee. Their conversation is interrupted temporarily when a man steers his car into her back alley, apparently looking for a date. He'll have to look for sex "elsewhere for a bit," Ann quips.

Ann says she needs supplies: blankets, food, candles, a healthy stock of condoms. All of that Thomason supplies. Ann also needs some crack, but she'll have to get that somewhere else.

Life questions

On the streets everything is a negotiation. And trading is a currency that Thomason and Laura Sterling, who also works with the women, are used to.

It might be six cigarettes and a car ride in exchange for honest information from one of the sex trade workers, including an estimate of their weight, height, and who to call if they turn up dead? Does she wear a bra or underwear, in case she disappears and one of those items turns up as some suspect's "trophy."

"It's like I'm paralyzed with fear," confides one woman, who Thomason hadn't seen in months but was found crouched in the entranceway of a building.

"I'm f***ing done," she sobs, as she describes how some men from Calgary chased her, one of them saying he had "claimed her." The skin under one of her eyes is fading from black to grey, the other still showing a scar underneath.

"I have to watch everything I do," she admits, casting sparkling green eyes over her shoulder. Her blonde hair is pulled back into a tight ponytail, her body twitching and rocking as she borrows Thomason's phone to call a friend.

"How much (drugs) you using a day babe?" asks Thomason, who can smoothly switch from straight-talking tough talk to an empathetic shoulder to cry on.

"Gram or two," the woman replies. She's been sober in the past, spent a year clean, she says.

A ham sandwich, given to her by Sterling, is inhaled between sobs.

"We believe in you," says Sterling, a mantra she convincingly wants the woman to believe. "You're so worth it. You've done this before. Trust that. Let's move it forward, you're worth it."

This woman's story, and the stories of others like her, are carefully recorded in notebooks by Thomason and Sterling.

Later that night, another woman who for months has tried to evade Thomason and her crew, is stopped on the street.

She's 29, her 'old man' or boyfriend is nearly double her age, she says. They've had five children together, the youngest, just two months old. All the children have been adopted or are in government care.

She struggles to remember the age of her one daughter.

"I don't see her," she says. "I think she's like four right now. I just see my last two boys, that's the only ones I see."

She is slight and pretty, wearing a short skirt. But her bare arms are deeply scarred. That too is recorded and photographed.

"In case something happens to you," explains Sterling.

"Sadly, we (may be) the last ones to see them alive before they go missing or get murdered," says Thomason.

Sterling closes the notebook and hides it "out of respect" as they approach another woman. The women know their casual chats and recorded information could be the last record of them alive, and that's why it is being collected, since many will never leave the street.

"They know what we're doing" Thomason says. "But to see it, pisses a lot of them off and it scares them."

Thomason and Sterling can only hope the notebook information isn't the first draft of an obituary they never want to read.