Got a beef with your neighbour over property lines? Good luck with that

A Nova Scotia man is facing the prospect of spending thousands of dollars to reclaim a small piece of woodland that his deed says he owns but the province's land registration system doesn't recognize.

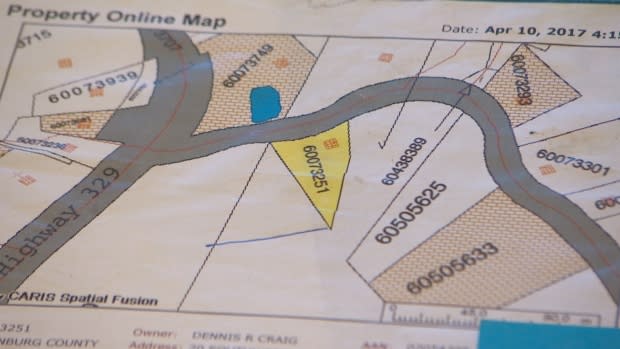

Dennis Craig has been trying for two years to get what he considers an inaccurate survey from 1974, which cuts his deeded property near Hubbards on the South Shore in half, removed from the province's land registration system.

"There seems to be no resolution for this at all," Craig said in a recent interview. "I have been to the association of land surveyors, I have been to the registrar general, I've been to the MLA, I've been to the executive registrar general, and then back around over and over again.

"Every time I climb a wall there's another one in front of me."

His predicament highlights what some who specialize in the field say is a problem with Nova Scotia's land registration system — unlike some other provinces, there's no simple mechanism to resolve property boundary disputes.

Craig bought his home in 1981 on a half hectare piece of land in Northwest Cove currently assessed at $124,000. At the time of the purchase, his title searcher discovered the property's deed was incorrect and was missing a boundary line. Instead of a rectangle, the property was a triangle. So the deed was amended and the missing boundary line restored.

Craig said he was unaware of any problems until he applied to have a septic system installed in 2016. The Department of Environment rejected his request, saying he didn't own some of the land where he planned to place the system.

It turns out his neighbour, whose land surrounds much of Craig's property, had surveyed their property in 1974. That survey, based on the old deed and missing a property line, was registered with the province. It shows half Craig's deeded property belongs to the neighbour.

Even the executive director of the Nova Scotia Association of Land Surveyors thinks the survey is questionable.

"It would appear that the survey was based on that deed and that there was an omission of one particular course," Fred Hutchinson said in an interview.

But Craig's request to have the mapping changed to reflect his deed and remove the incorrect survey was rejected by Peter Craig (no relation), a senior mapper with the Lunenburg County Land Registration Office.

In an email, Dennis Craig was informed it is "accepted practice" to use the survey to map the property online "as it would have more weight in this instance than the description of the property."

"Although your description appears to possibly describe the property in a different configuration than we have mapped, we have a registered survey plan on file which appears to show the configuration as we have it mapped," Peter Craig wrote.

The surveyor who Dennis Craig says produced the inaccurate survey has died, so there is no opportunity to present him with evidence to amend his work.

Instead, Norman Hill, the executive director of the province's registries, told Craig in an email to do his own survey and get a boundary line agreement from the neighbour so the mapping can be corrected. Hill told Craig his land is mapped the way it is "because his neighbour's survey is the best evidence we have of where the boundaries are."

The Miller family, which owns the neighbouring land, say they sympathize with Craig, but disagree with his position. Lawson Miller said his family feels the 1974 survey is an accurate representation.

Craig has hired a surveyor and plans to register the work so the land will be shown as "disputed." His only other option is to take his neighbour to Nova Scotia Supreme Court and ask a judge to set the boundary, something that could take years and cost thousands of dollars.

N.B. has process to resolve disputes

Craig's lawyer wrote to the Association of Nova Scotia Land Surveyors alleging "negligence" by the surveyor who left out the boundary line, and questioning who was going to pay Craig's legal bills and the cost of a new survey.

The association responded by pointing out there is a 15-year statute of limitations on such claims, but acknowledged there is "absolutely" a problem with how the land titles office deals with discrepancies.

"It's very, very important that we are able to determine where properties are and the accuracy of the mapping," Hutchinson said in an interview.

He cites what New Brunswick is doing as a possible solution. That province has a system where the registrar general of land titles will hear from owners locked in a property dispute and then rule on where the boundary should be. The aim is to avoid the expense of going to court and to resolve situations more quickly.

Craig wants to see Nova Scotia adopt something similar. His only recourse right now it to go to court, and he feels like he's "kind of dead in the water."

Hutchinson said information on the New Brunswick initiative was sent to the Nova Scotia government a year-and-a-half to two years ago, but so far "there's been no response, really."

System needs support

He calls Nova Scotia's land registration system "one of the best in the country," but said it has not had the financial or staffing support it should have over the past several years.

He also points out there is no land surveyor on staff at the land registry, someone who could "review survey plans or have any kind of authority to ferret out issues that could be resolved."

"That would be nice if the registrar general, with the support of a land surveyor, had the authority to make a decision on which plan supersedes the other," he said.

Catherine Walker, a lawyer who specializes in property law, feels an alternative to court would be useful for property disputes.

"The more dispute resolution mechanisms we have outside court, the better for everyone," she said in an interview.

Service Nova Scotia Minister Geoff MacLellan doesn't seem convinced. He said last week there are no plans to change the way the land registration system operates "from a policy or a law perspective."

He maintains boundary disputes need to be ironed out by the courts, leaving Craig and his neighbour in limbo.