How a Group of Lawyers Is Using Design to Change What We Know About Systemic Racism and Racial Violence in America

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice will reopen on June 15 after being closed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Sia Sanneh, a senior attorney with the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative, believes combatting injustice depends, at least in part, on storytelling. Not just the case law–backed kind of storytelling one expects to hear from a civil rights lawyer who has spent much of her career dedicated to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States and challenging racial and economic injustice, but a more visual kind, with the potential for broader impact, one that harnesses the powers of our built environment to influence how we feel.

“When we see an injustice in the world, Bryan [Stevenson, founder of EJI] encourages us to think about a policy or law that is perpetuating it, but also to consider the broader story behind it,” says Sanneh. “We think of our legal work as so much more than case law, because courts do not exist in isolation from our environment. We also try to reach people where they are by telling a story the way people can understand it.”

This is what drove a handful of lawyers to create the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a deeply moving and hauntingly beautiful memorial dedicated to the legacy of victims of systemic racism, particularly those terrorized by lynching during Reconstruction and racial violence that still occurs today in our country.

In wake of George Floyd's murder, it's clear just how important memorials and museums dedicated exposing these truths are to reshaping the way we think and our policies.

Of course, the memorial didn’t materialize overnight, and Stevenson and Sanneh didn’t work alone to realize their idea. Instead, the Montgomery, Alabama, landmark, which opened in 2018, is the result of nearly a decade of research, building, and collaborating between the EJI attorneys and a team of designers, artists, sculptors, and architects, including MASS Design Group, which helped build the memorial square on top of the six-acre site’s hill.

We sat down with Sanneh to discuss how the memorial’s thoughtful design helps EJI achieve its mission of challenging racial and economic injustice. Below is an excerpt from our interview.

Where did the idea for this memorial come from, and what kind of research did you do to inform its creation? Did you visit other sites?

We started thinking about other countries that have had to overcome violence and how meaningful spaces of remembering have been for healing and overcoming that violence.

Bryan and I have both visited the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, South Africa, the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Rwanda, and the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. And we began to think about what it would be like to have a space like that in Alabama, a narrative space that would teach people, but also provide a space for people to reflect and grieve.

Because there is not really a shared understanding of the history of lynching in this country, we conducted a research project that took over six years, in which we attempted to document every lynching that occurred first in Alabama, then the Deep South, the South, and the rest of the country.

By the end, we had over 4,000 cases between 1877 and 1950, with stories behind each case. We felt the loss so profoundly, and the process itself, from pulling out records at county courthouses to visiting over 180 sites where we now know lynchings occurred, really gave us design ideas to create the memorial space.

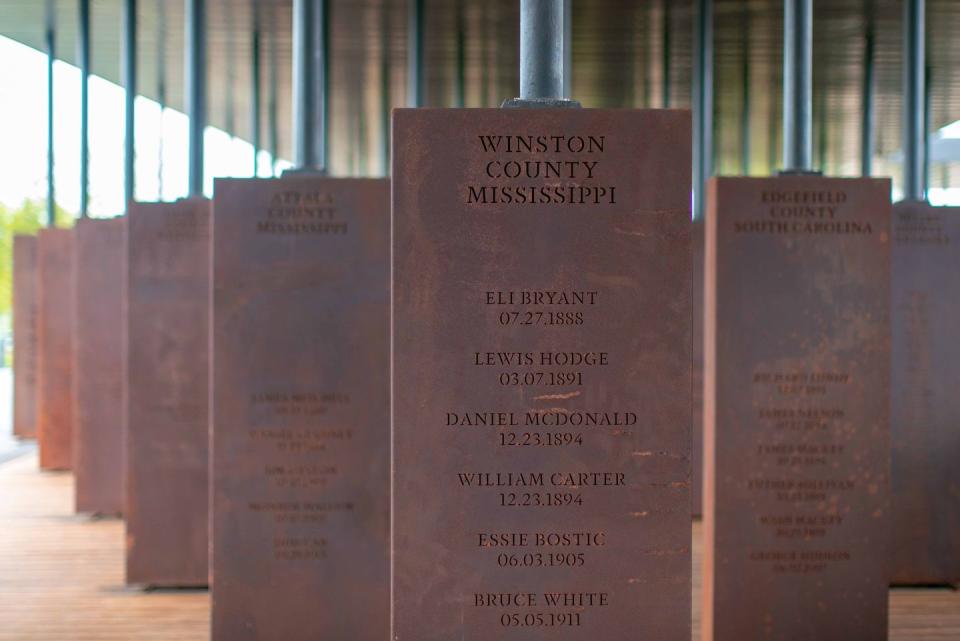

In the memorial structure at the top of the hill, you have paid tribute to their lives with the creation of monuments that list each victim you documented by the county where the lynchings took place. How did you design the monuments themselves?

We wanted a more abstract design for the monuments to rebut the very sensational imagery that came out of the lynching era. We are, unfortunately, so desensitized to violent images.

Yet, we also wanted the monuments to feel personal. The rectangular boxes are made of corten steel, which changes color with exposure to the elements. It creates this effect where no two monuments look the same…just as there is not one shade of black people in America.

The metal also replicates the variations in the soil of the South, and it lends a very human effect to this abstract representation of a person. We felt like there was something very solemn and desensitizing about presenting them in this way.

One of the most moving parts of the memorial is how one’s interaction with the monuments evolves as one moves through the temple-like structure. What drove the design decisions behind this?

We wanted to create a space that replicated the scale of the tragedy but in a very personal way. We also wanted to capture that these were really local events that affected people at a local level. So we included personal details about each victim on each monument.

When you enter the memorial structure, you encounter the monuments at eye level first, which lets you process that these are people. As you move through the corridors, you gradually descend down a wooden walkway, creating the effect that the monuments are hanging above you.

What role does sculpture play at the memorial?

We knew visitors to the memorial would not have a shared understanding of this history, because it has been hidden for so long. So we wanted to make the space a narrative one, one that shares the story from beginning to end. The sculpture that you see before you enter the memorial structure and after you leave it gives context for that specific period of time.

I am particularly moved by Dana King’s piece depicting three women who led the Montgomery Bus Boycott that you see when you leave. It’s incredibly hopeful to consider how they mustered the strength to do that after growing up in the era of lynching.

Tell me about the site and how you chose it. Why is it important that the memorial is outside?

The memorial sits on a hill just outside of downtown Montgomery. From the top, a visitor can see all the way down to the Alabama River, which helped Montgomery become one of the most active slave-trading spaces in the country. And you can also see the state Capitol where Martin Luther King, Jr., led a demonstration and today’s courthouses. We are a Montgomery-based organization, and we really wanted there to be a through-line from the city’s origins to the present day.

Being outside helps visitors have enough space to process the scale of what happened. When you’re leaving the memorial, it helps to have some open sky to help process what you just experienced and just how expansive this history was. You really cannot understand American history without knowing this period intimately.

What was it like for you, personally, to work on this project?

I am the daughter of a historian, and I myself studied history at the undergraduate and graduate levels before going to law school. Yet, as much as I have read in books, working on this project helped me see what, as a country, we haven’t talked about as much.

We sought to understand what the narrative was that allowed this to continue to occur and how this affected everybody, not just the specific targets of the violence. Design is better positioned to help us answer, or try to tackle, these difficult questions.

What has been the most meaningful feedback you have received from people who have visited the memorial?

One of the things we are most proud of is how so many people of different backgrounds have been able to be affected by it. It’s very powerful and exciting to witness people from all over the world making pilgrimages to Montgomery to see this and be moved by it.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is located at 417 Caroline Street in Montgomery, Alabama. It's open every day except Tuesdays 9 a.m. - 5 p.m. General admission tickets cost $5; admission for children ages 6 and under is free.

You Might Also Like