Harry Litman: The ominous return of Bush vs. Gore

These are the most foreboding words seen for some time in a Supreme Court opinion: “As Chief Justice Rehnquist persuasively explained in Bush v. Gore…”

The phrase, which appeared this week in a concurrence written by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, sounds like grinding gears to anyone who thinks the election-deciding fiat in Bush vs. Gore was a terrible stain on the court's credibility.

Which is to say, just about everyone in the legal profession.

It also portends a nightmare scenario: a repeat in 2020 of that widely discredited decision, which stopped the recount of the vote for president in Florida in 2000.

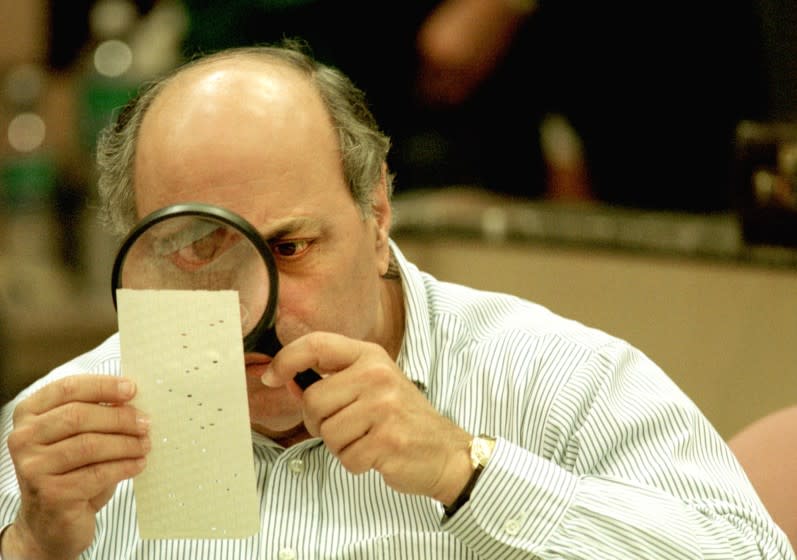

The deciding principle of Bush vs. Gore is generally understood to be no more than this: George W. Bush wins. Or, to be as charitable as possible toward the five members of the court who made up the majority: The ruling was necessary to stop the partisan bloodletting and chaos generated by hanging chads in Florida.

The decision was so tenuous and rushed that the justices themselves, in a stunning departure from judicial practice, wrote into the unsigned opinion that it should not serve as a precedent: It was “limited only to the present circumstances.”

Nonetheless, Kavanaugh on Monday embraced the most far-fetched theory laid out in Bush vs. Gore, in a separate opinion written by Rehnquist, who was straining to figure out a way to insert the court into the Florida mess.

The recount in that state had been ordered by the Florida Supreme Court, ruling that it was required by the state's Constitution and its election laws. It is axiomatic that state supreme courts have the final authority to interpret state laws; the U.S. Supreme Court may intercede only if an interpretation conflicts with federal law. For the high court to step in, Rehnquist needed to find a federal constitutional violation in the Florida Supreme Court’s order.

The chief justice’s justification, which only Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas adopted, was based on a phrase in Article II of the Constitution: The states are to appoint presidential electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” Rehnquist posited that these words allowed a federal court to reverse a state court’s decision on state election law if the federal court determined the state court had clearly departed from the intent of the state Legislature.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent in Bush vs. Gore slammed the idea as grasping at straws. Rehnquist’s rationale, she wrote, “contradicts the basic principle that a State may organize itself as it sees fit.”

Bush vs. Gore muscled Bush into the presidency in 2000, but in the broad judgment of the legal community, Ginsburg was right: It is illegitimate for the court to arrogate to itself the determination of whether a state supreme court has been faithful to state law.

Kavanaugh’s shout-out to Bush vs. Gore on Monday came in a “shadow docket” case — Democratic National Committee vs. Wisconsin State Legislature. He and the other justices vacated a federal appeals court decision that had extended a ballot deadline in Wisconsin. The case did not turn on the question of when or if the U.S. Supreme Court can intervene in a state court's decisions about its elections, but Kavanaugh worked Rehnquist’s idea into his concurrence anyway: “The text of the Constitution,” he wrote in a footnote, “requires federal courts to ensure that state courts do not rewrite state election laws.”

The fact that Kavanaugh’s invocation of Bush vs. Gore had no real relevance to the issues in Democratic National Committee vs. Wisconsin suggests that it was a marker laid down by the justice. In the potentially tumultuous weeks ahead, it seems certain he would be prepared to push the court into a confrontation and a result similar to the showdown in Florida in 2000.

And he may not need to push very hard. On Wednesday, Justices Thomas, Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Neil M. Gorsuch filed a statement in a Pennsylvania balloting case suggesting that they too believe that the high court is empowered to reverse a state supreme court decision that “squarely alters” election law enacted by a state legislature. Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who started her new job at the court on Wednesday, did not take part in the consideration of the case, but who would be willing to wager that she will not jump to join her four archconservative brethren if the opportunity arises?

Any endorsement of the outlier decision of Bush vs. Gore should be seen for what it is: an early warning that the newly reconstituted Supreme Court is primed to wrest a contested state election result away from the state, and possibly from the will of the majority, all based on a legal principle in broad disrepute.

The harm to the court’s reputation, and more importantly to the will of the people, could be incalculable.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.