What is herd immunity and how do we reach it?

Pandemics typically end in one of two ways: cases are tracked and isolated or a population achieves herd immunity, often with the help of a vaccine. Most experts agree containment of the coronavirus is no longer possible. What about herd immunity?

What is herd immunity?

Angela Rasmussen: When enough people in a population are immune to the virus, it can’t find a new host, and therefore, it won’t be able to spread through that population. This applies mostly to viruses, which need a host to replicate.

Marc Lipsitch: It’s the extent to which immunity in the population helps to insulate individuals who are not immune from infection.

What is the threshold for reaching herd immunity?

Lipsitch: It depends on the virus, the population and on the nature of immunity. The more contagious the virus, the higher the threshold for herd immunity. Some populations have more transmission than others because they’re so densely populated and have more interactions with one another, so that also affects the threshold for herd immunity. Last, it is a question of how good the immunity to this virus will be. If it’s not very effective or short-lived, then herd immunity becomes much harder to achieve.

Amber D’Souza: It depends on the infection, but for most, it’s around 70% of the population.

Related: How quickly will there be a vaccine? And what if people refuse to get it?

What if we don’t reach that threshold – if, say, a large segment of the population refuses to be vaccinated?

D’Souza: If we have a vaccine, and only 40% or 50% of people become vaccinated, we don’t achieve herd immunity. The infection will continue to spread among those who are not protected.

Rasmussen: We’ve seen this most clearly with the increase of measles transmission around the world. The number of people who are not vaccinated against measles has grown, and we’re starting to see outbreaks in populations that previously had herd immunity.

Is herd immunity the only way to end a pandemic?

Rasmussen: Not necessarily. The [2002–2004] SARS outbreak could be considered a pandemic in that there were outbreaks outside of Asia. But only 8,000 people were infected, and it was not transmitted pre-symptomatically. It was controlled using classical epidemiological methods, like testing, tracing, quarantine and isolation.

But for this pandemic, there’s so much transmission around the world, I think it’s the only way it ends is with a vaccine.

Are there any diseases for which we already have herd immunity?

D’Souza: Many. We have effective vaccines for chickenpox, measles, mumps and rubella. Vaccines against those diseases are widely distributed, and we see very low rates of transmission in our population. You’ll still get occasional outbreaks when vaccination dips, but as long as the population at large has herd immunity those outbreaks will be contained.

Are there diseases for which we have achieved natural herd immunity?

Rasmussen: There’s still a lot we don’t understand about this. Zika no longer appears to be circulating in South America, and its thought that that’s because natural herd immunity has been reached. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other vulnerable populations – it could reemerge.

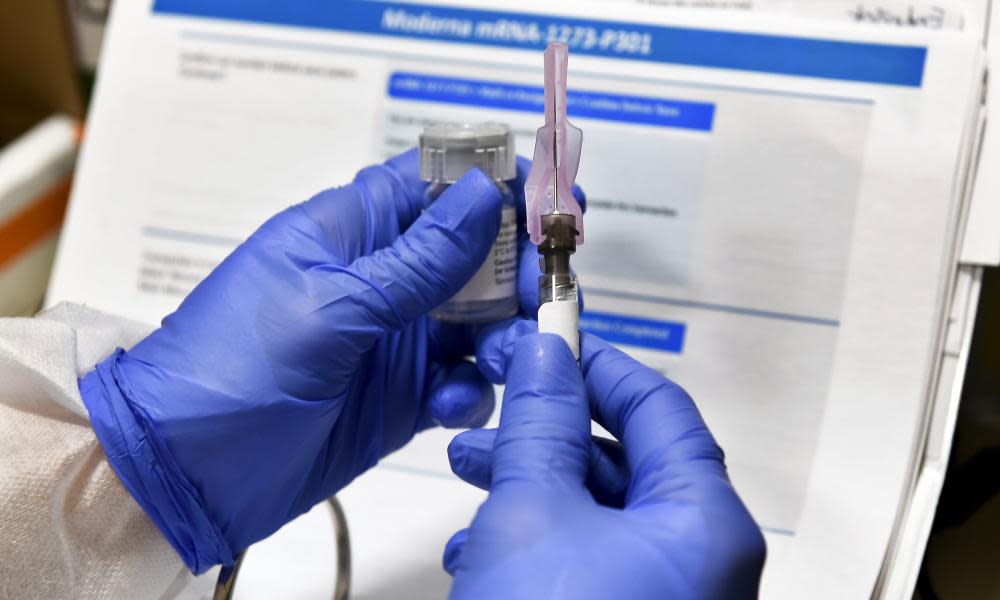

If a Covid-19 vaccine is released, how long would it take to reach herd immunity?

Rasmussen: It depends on how many people take the vaccine and how well the vaccine works. Vaccines for a lot of respiratory pathogens don’t always give complete sterilizing immunity, meaning that you might still be able to be infected – you just won’t get as sick. That’s still a huge public health benefit, but it also makes it more difficult to figure out how many we need to vaccinate to get herd immunity because you may still have hosts that are capable of harboring the virus.

So it depends on your definition of herd immunity. Will you be able to eradicate the virus with these vaccines? Hard to say. But even if it doesn’t completely prevent the virus from spreading in the population, it does affect how we’re going to be able to go back to “normal.”

Lipsitch: Ideally, we’ll get to a point where it’s like the measles. Well-functioning communities will have high vaccination rates and herd immunity. You do worry about importations from those who can’t get the vaccine that year, but it wouldn’t be a daily worry for most people.

Is there any possibility that we could achieve natural herd immunity to Covid-19?

D’Souza: The data suggest that nationwide, maybe 10% of Americans have been exposed. We’re not even close to achieving herd immunity through natural infection at this point.

Rasmussen: The idea that, “Well, we’re just stuck with it, so let’s all just get it over with and we’ll all have herd immunity”, is just not done. It would cause the deaths of millions of people and potentially the permanent disability of millions more. We can’t afford to pay that type of epidemiological price for herd immunity. We need to wait for a vaccine.

Lipsitch: The problem is that we’ll suffer in the process. So, it’s not that we can’t do it, it’s that we don’t want to do it, given the damage that we now know that it can cause.

I don’t think it’s scientifically wrong, I think it’s morally wrong.

Panelists

Dr Angela Rasmussen, virologist and associate research scientist, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Dr Amber D’Souza, professor of epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health

Dr Marc Lipsitch, professor of epidemiology and director, Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health