Here's What to Know About the Summit Between Joe Biden and Moon Jae-in

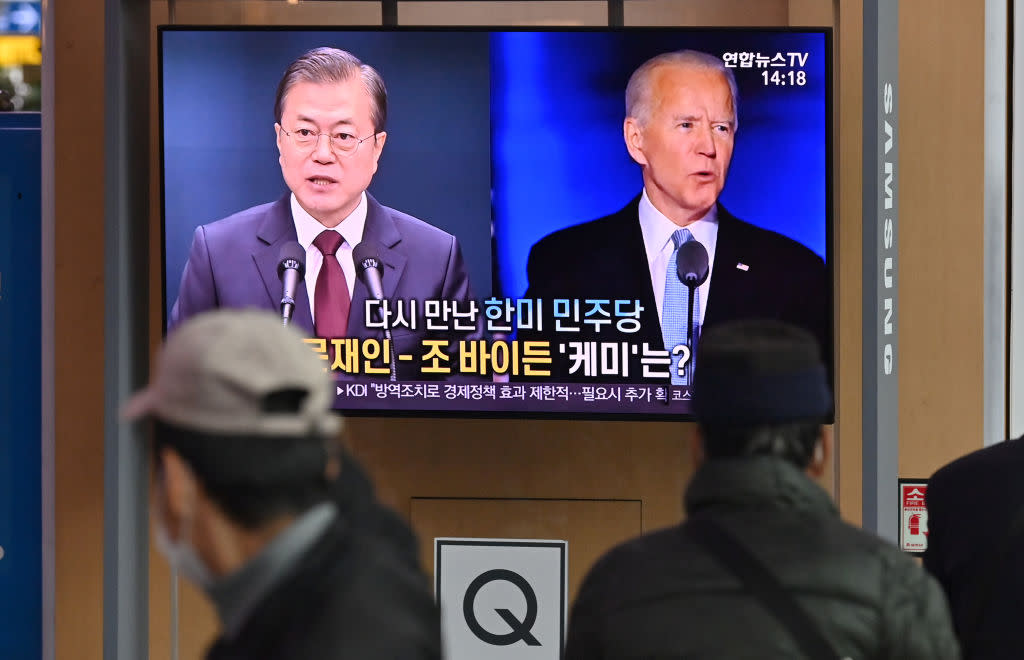

People watch a television news programme reporting on the US presidential election showing images of US President-elect Joe Biden (R) and South Korean President Moon Jae-in (L), at a railway station in Seoul on November 9, 2020. Credit - JUNG YEON-JE/AFP via Getty Images

On Friday, U.S. President Joe Biden and his South Korean counterpart Moon Jae-in meet at the White House as two leaders united by the goal of reining in an autocratic, nuclear-armed, East Asian state.

Unfortunately both men have very different approaches when it comes to North Korea. Moon wants Biden’s commitment to secure a lasting peace with Pyongyang. Biden wants Moon to play a greater role in countering North Korea’s greatest ally, China.

Each has his reasons for evading the other’s expectations. North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has slowed down missile tests—and that makes North Korea one of the many crises in Biden’s in-tray that he will be happy to mark ‘pending.’ Moon is meanwhile wary of the economic retaliation that standing up to Beijing inevitably brings.

But that doesn’t mean the summit will be a dud. Both leaders can help each other in different areas, with vaccine procurement, economic recovery and regional alliances high on the agenda.

U.S. Vaccines for Korean Semiconductors?

South Korea has managed to keep its COVID case tally to 132,290 out of a population of nearly 52 million, with 1,903 deaths—but a struggle to obtain vaccine supplies is threatening to overshadow this relative success. South Korea has so far vaccinated less than 5% of its citizens and pressure is mounting to secure more shots fast.

Seoul’s goal of achieving herd immunity by November has been undermined by global vaccine shortages and shipment delays. Its attempts to acquire surplus U.S. jabs have not so far received a positive response, with White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki instead talking up vaccine cooperation among members of the new Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad)—comprising the U.S., Japan, India and Australia.

Moon will be wanting to change that and his trump card may be the new $17 billion semiconductor foundry that South Korean giant Samsung is reportedly preparing to open in the U.S. in addition to its existing facility in Austin, Texas. Biden has spoken about “the need to build the infrastructure of today and not repair the one of yesterday” and this would fit neatly into $2 trillion infrastructure plan, which includes $50 billion for semiconductor manufacturing and research.

A joint announcement of a vaccine deal, plus South Korean investment-linked jobs, would allow both sides to leave the summit claiming a big success.

Biden’s plan for North Korea

Things are less clear-cut when it comes to North Korea. Biden’s North Korean policy review, unveiled last month, signals that Pyongyang is not an immediate concern. “Our policy will not focus on achieving a grand bargain, nor will it rely on strategic patience,” Psaki has said.

The fact that taming North Korea’s nuclear threat is not top of Biden’s priority list will be a source of frustration for Moon, the son of refugees from North Korea. With less than a year left in office, he has been eyeing a lasting peace on the peninsula as his legacy and is desperate to salvage some momentum from the 2018 Singapore summit between Trump and Kim.

To that end, he has lobbied for sanctions relief, banned conservatives from sending propaganda leaflets into North Korea and postponed join military maneuvers with Washington. But such moves have led many in Washington to regard Moon as far too lenient on Kim, and Biden will have no problem waiting, perhaps even hoping, for a South Korean leader more attuned to his viewpoint.

While Moon will want to play the same mediating role as he did between Kim and Trump, the former president’s Asia team lacked the deep understanding and wherewithal to build on that summit with detailed negotiations. “Biden’s team is better set up to actually do that stuff.” says Prof. John Delury, an East Asia specialist at Seoul’s Yonsei University.

At the same time, it is difficult to imagine what inducements might be offered to Pyongyang to rekindle talks. North Korea went into complete lockdown earlier than anyone after the pandemic hit and will probably come out of it later, too. Kim has even rejected foreign food aid for fear that it might bring in the virus.

“The Kim Jong Un regime will come to the table only if something very substantial is offered,” says Prof. Sean O’Malley, an international relations specialist at Dongseo University in Busan, South Korea. “Otherwise, they won’t come forward. They have no interest in denuclearization.”

Boosting the U.S. Alliance

Moon will be only the second world leader Biden has welcomed to the White House, after Japan Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, and it is no coincidence that America’s East Asian allies top the guest list. Biden will be hoping to tease some greater cooperation from Moon, perhaps even formal engagement with the Quad, whose members profess “a shared vision for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” according to a joint statement earlier this year.

The U.S. wants to beef up the foursome into a “Quad Plus,” including South Korea, New Zealand and some Southeast Asian nations like Vietnam. Beijing, of course, sees the Quad as the latest manifestation of a U.S. policy of containment—and South Korea could expect severe blowback were it to signal any participation. (South Korea got its fingers badly burnt by economic retaliation in 2016 when it agreed to accept U.S. THAAD antimissile batteries).

Suga departed Washington having made a joint statement that stressed the importance of “peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait.” (China considers democratic Taiwan a breakaway province and has vowed to reunite it by force if necessary.) Most analysts believe that Moon will refrain from similar statements on the self-ruling island to avoid angering Beijing.

However, he has been more forthright about Myanmar, where at least 715 peaceful pro-democracy protesters have been killed since the Feb.1 coup d’état. Moon was imprisoned by South Korea’s military as a student activist and his nation’s fight for democracy of the 1980s remains seared into the memories of older South Koreans, who have expressed solidarity with the struggle unfolding in Myanmar.

“There’s a lot of public support [in South Korea] for a stronger stand on Myanmar,” says Delury. “It could be almost an outlier issue to reassert the alliance stands for positive values like democracy.”

Correction, May 20

An earlier version of this story misstated when the summit will take place. It takes place on Friday, May 21.