Hidden tunnel under Mayan temple reveals new gruesome details of human sacrifices

Twin boys were often slaughtered in human sacrificial rituals at a notorious Mayan temple, new research has revealed

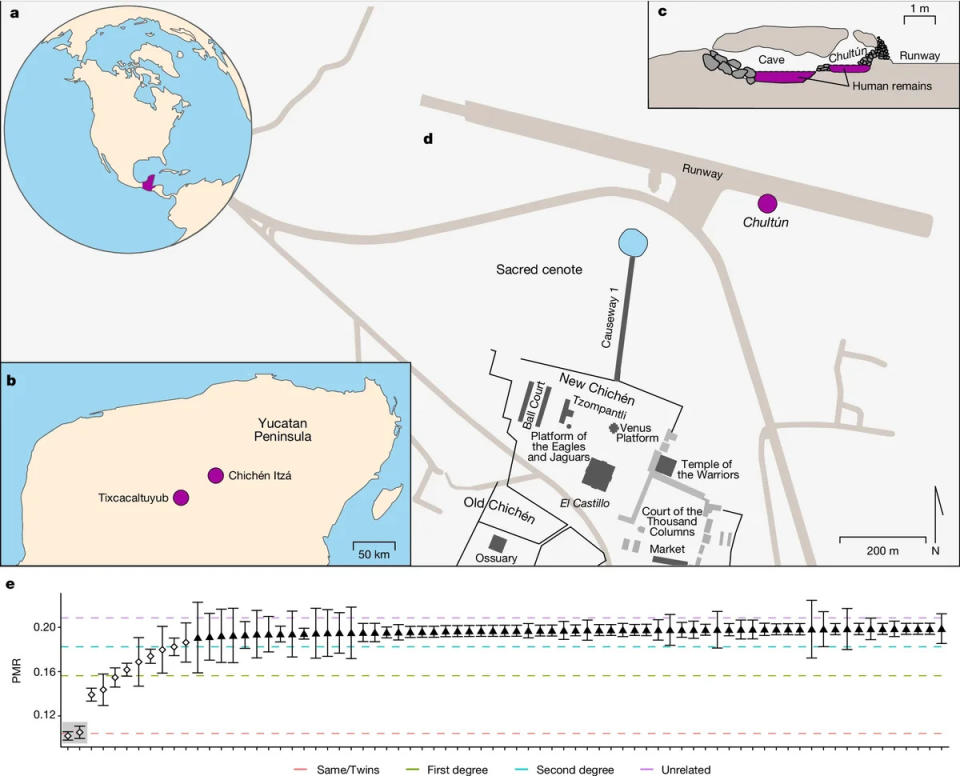

The grim discovery was made after ancient human remains found in the ancient city of Chichen Itza were analysed using state of the art technology by an international team of scientists.

The findings, published in the journal Nature, disprove previous theories that the majority of the victims of human sacrifice in the city's temples were girls or young women.

Located in present day Mexico, Chichen Itza is one of North America’s most iconic archaeological sites.

It was a powerful political centre in the centuries before the arrival of the Spanish.

The city is known for its monumental architecture including the huge temple of El Castillo adorned with feathered serpents.

Extensive evidence of ritual killing, including both the physical remains of sacrificed individuals and representations in monumental art, have been previously uncovered at Chichen Itza.

Dredging of the site’s Sacred Cenote in the early 20th Century identified the remains of hundreds of victims, and a full-scale stone representation of a huge tzompantli, or skull rack.

But the role and context of ritual killing at the site had not been previously analysed in detail.

It was known that many of the people sacrificed there were children and adolescents.

Although there was widespread belief that females were the primary focus of human sacrifices at the site, researchers say it it is difficult to determine sex from juvenile skeletal remains by physical examination alone.

More recent anatomical analysis suggests that many of the older juveniles may in fact have been boys.

A subterranean chamber, known as a chultún, was discovered in 1967 that contained the scattered remains of more than 100 children.

The chamber had been enlarged to connect to a small cave.

Such subterranean features were widely viewed as connection points to the underworld.

Researchers conducted an in-depth genetic investigation of the remains of 64 children ritually interred within the underground chamber.

Dating of the remains revealed that the chamber was used for mortuary purposes for more than 500 years, from the 7th to 12th Centuries AD, but that most of the children were interred during the 200-year period of Chichen Itza’s political apex from 800 AD to 1000 AD.

The genetic analysis revealed that all 64 tested individuals were boys.

Further genetic analysis revealed that the children had been drawn from local Maya populations, and that at least a quarter of the children were closely related to at least one other child in the chamber.

The young relatives had consumed similar diets,-suggesting they were raised in the same household, say scientists.

Study co-author Dr Patxi Pérez-Ramallo, of the Max Planck Institute, Germany, said: “Our findings showcase remarkably similar dietary patterns among individuals exhibiting a first- or second-degree familial connection."

Co-author Dr Kathrin Nägele, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said: “Most surprisingly, we identified two pairs of identical twins.

“We can say this with certainty because our sampling strategy ensured we would not duplicate individuals.”

Taken together, the research team say their findings indicate that related male children were likely being selected in pairs for ritual activities.

Co-author Oana Del Castillo-Chávez said: “The similar ages and diets of the male children, their close genetic relatedness, and the fact that they were interred in the same place for more than 200 years point to the chultún as a post-sacrificial burial site, with the sacrificed individuals having been selected for a specific reason."

The research team explained that twins hold a special place in the origin stories and spiritual life of the ancient Maya.

Twin sacrifice is a central theme in the sacred K’iche’ Mayan Book of Council, known as the Popol Vuh, a colonial-era book whose antecedents can be traced back more than 2,000 years in the Maya region.

In the Popol Vuh, the twins Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu descend into the underworld and are sacrificed by the gods following defeat in a ballgame.

The twin sons of Hun Hunahpu, known as the Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque, then go on to avenge their father and uncle by undergoing repeated cycles of sacrifice and resurrection in order to outwit the gods of the underworld.

The Hero Twins and their adventures are often represented in Classic Maya art, and because subterranean structures were viewed as entrances to the underworld, researchers say the interment of twins within the chamber at Chichen Itza may recall rituals involving the Hero Twins.

Co-author Professor Christina Warinner, of Harvard University in the US, added: “Early 20th Century accounts falsely popularised lurid tales of young women and girls being sacrificed at the site.

“This study, conducted as a close international collaboration, turns that story on its head and reveals the deep connections between ritual sacrifice and the cycles of human death and rebirth described in sacred Maya texts.”