Are Hispanic and Black children more at risk of COVID? ‘It’s a trickle down’ effect

Children and teens don’t usually get the worst COVID-19 symptoms. They might cough a lot, have a runny nose, maybe get a fever. Most recover.

But some wind up in the hospital. Some die.

And many of those who have died from COVID-19 related complications are Hispanic or Black, according to a new report published this month by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The report looked at 121 COVID-associated deaths under age 21 that were reported to the CDC from Feb. 12 to July 31. Of those deaths, 45% of the young people were Hispanic, 29% Black, 14% white non-Hispanic and 4% American Indian or Alaska Native.

Most had at least one pre-existing medical condition, which, like with adults, increased their risk of seriously falling ill with the disease. Fifteen of them were also diagnosed with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, a rare and serious sometimes deadly inflammatory disorder believed to be linked to COVID-19.

“This pandemic is pointing out the need for children to continue to stay in medical care, continue to have their checkups, continue to get their vaccinations, and if they have a chronic underlying condition, continue in medical care to make sure that condition is managed,” said Dr. Danae Bixler, a CDC medical officer who led the research.

Researchers learned that Hispanics, Blacks and American Indian/Alaska Natives accounted for approximately 75%-78% of the COVID-associated deaths in children, teens and young adults despite representing 41% of the U.S. population under 21.

They also learned deaths were more prevalent among males and among people age 10 to 20, with young adults 18 to 20 accounting for nearly half of all COVID-associated deaths in this population.

The findings came from analyzing death data retrieved from health departments across the country and from some U.S. territories. The data included demographic and hospitalization information, if a person had underlying medical conditions, where the death happened, and whether the person was considered a COVID-19 or MIS-C case or both.

The report notes at least five limitations about its research, including a likely undercount of cases and deaths because of incomplete testing, missing demographics and delays in reporting and verification. Another limitation was that the “majority of U.S. early child-care providers, schools, and other educational institutions were closed, gatherings of children and adolescents were reduced, and testing and treatment protocols changed,” the report states.

The report also mentions how important it is to monitor COVID-19 infections, deaths and other severe outcomes, like MIS-C, in kids and adolescents as schools reopen across the country.

“Ongoing evaluation of effectiveness of prevention and control strategies will also be important to inform public health guidance for schools and parents and other caregivers,” reads the report.

The findings, published by the CDC in “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,” matched what health officials were already seeing in the adult population for several months — Blacks, Hispanics and other people of color have a higher risk of getting sick, being hospitalized and dying from COVID-19.

Why are minorities more at risk of falling ill with COVID-19?

Experts say the reason why minorities have a higher risk of becoming ill with COVID-19 likely involves social and economic factors. The report lists several reasons, including crowded living conditions, food and housing insecurity, wealth and educational gaps and racial discrimination. Health conditions and access to healthcare also are factors.

“While there’s no evidence that people of color have genetic or other biological factors that make them more likely to be affected by COVID-19, they are more likely to have underlying health conditions,” Dr. William F. Marshall, a Mayo Clinic infectious disease specialist, wrote in a blog post.

“Having certain conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, increases your risk of severe illness with COVID-19,” he wrote. “But experts also know that where people live and work affects their health. Over time, these factors lead to different health risks among racial and ethnic minority groups.”

Bixler and her team also noted in their data analysis that racial/ethnic groups are “disproportionately represented” among essential workers.

Since essential employees work at restaurants, stores, day-care centers, grocery stores, transit systems, hospitals, nursing homes and other businesses that are considered essential, they come into contact with more people, increasing their risk of infection.

They then return home, possibly to a crowded multi-generational household, where they may infect other family members, including babies, children, young adults, parents and grandparents.

It’s a “trickle down” effect, said Dr. Juan Pablo Solano, a pediatric intensivist at Holtz Children’s Hospital in Miami and an assistant professor of pediatric critical care at the University of Miami.

Bixler and Solano believe limited healthcare access, such as being uninsured or not having access to paid sick leave, may also play a role in how COVID-19 is affecting minorities. Some people could also still be scared of visiting their doctor or the ER during the pandemic.

While many of the COVID-associated deaths in kids, teens and young adults happened in hospitals, the report also notes that a “substantial proportion” of deaths occurred outside of the hospital. The highest proportions of deaths at home or in the ER in this age group occurred in infants and people age 14 to 20, a concerning sign that families might be waiting too long to seek help, experts say.

Since the report’s cutoff date, the number of COVID-19 cases in adults and children has grown though it’s difficult to have an exact count of how many children tested positive or died from the disease nationwide. The pediatric data available varies from state to state.

Of the millions of COVID-19 cases in the United States, at least 587,948 are children, according to the most recent report published by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Florida has had more than 57,000 children under 18 test positive for the disease since March, according to the Florida Department of Health. Of those, 716 have been hospitalized and eight have died.

At least six of the children in Florida who died had multiple pre-existing medical conditions, according to medical examiner reports acquired by the Miami Herald.

How does COVID-19 compare with influenza in children?

COVID-19 shares many similar symptoms with the flu, though they are caused by two different viruses, and the COVID mortality rate is thought to be substantially higher than most flu strains, according to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. This made it difficult for doctors to diagnose people with the novel coronavirus at the beginning of the pandemic, when little was known about the virus and testing was scarce or nonexistent.

While experts don’t believe children are at higher risk of falling ill with COVID-19 than adults, children in general are more likely to be exposed to, and fall ill with, the flu than people in other age groups, and are considered to frequently be the drivers of spreading influenza in the community, the CDC told the Miami Herald in an email.

There is also data to suggest that racial and ethnic minority groups “bear a disproportionate burden” of flu hospitalizations compared to white non-Hispanics, the CDC said.

“Unpublished CDC data that looked at hospitalization rates in CDC’s flu hospitalization surveillance network found that during flu seasons from 2009-10 through 2018-19, children hospitalized with flu were more likely to be non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native; non-Hispanic Black; or Hispanic or Latino, compared to non-Hispanic White,” the CDC said in the email.

While COVID-19 deaths in children are rare, Bixler says people need to remember that the risk of death from any cause in children is very low, so when it does happen, it’s a concern. Young adults have also recently begun to test positive more for the disease than older adults and are considered to be a major factor in the virus spread.

Bixler said parents also need to pay extra attention now that schools are reopening across the country.

“Parents, stay in touch with their doctor. Keep your child well. Keep those immunizations up to date. Keep those chronic conditions managed and take this seriously,” Bixler said. “Most of the time, children will come out on the other side OK, but there are those rare advances that we have to stay alert for.”

She added: “We can’t lose our children throughout the course of this pandemic.”

South Florida has more than half of state’s MIS-C cases

Monitoring your child’s health is especially important now that doctors are grappling with MIS-C, a rare but serious and sometimes deadly complication associated with COVID-19 that can affect people younger than 21.

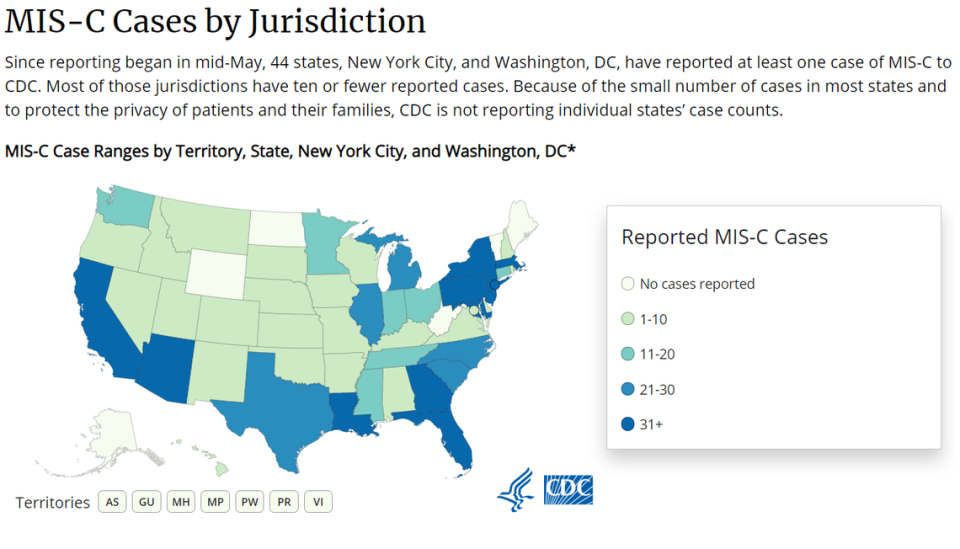

The CDC has recorded a total of 935 confirmed MIS-C cases in the country and 19 MIS-C associated deaths, with most of the cases occurring in children between the ages of 1 and 14. More than 70% of reported MIS-C cases occurred in children who are Hispanic or Black.

The syndrome is described as swelling that can affect “multiple body systems” including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes and gastrointestinal organs. Most children who fall ill with MIS-C tested positive for COVID-19 or its antibodies. Others were recently around someone who had the disease. Symptoms normally appear two to four weeks after infection and most children recover.

For Lexanni Perez, a 5-year-old girl in Polk County, her illness began with a 105-degree fever and “intense bellyaches,” WFTV reported.

She tested negative for COVID-19, was taken to her pediatrician and then the hospital. After four days, she was confirmed to have MIS-C.

“When doctors were doing their rounds, and they would say, 5-year-old girl presenting heart failure and cardiac failure, I almost had to hold onto the railings every time because I just didn’t understand how we got here,” the girl’s mother told the station in August. “Just seeing your child there in a hospital bed. It’s just … hopeless.”

Lexanni has since recovered, WFTV reported.

As of Friday, Florida has confirmed a total of 70 MIS-C cases and more than half are Hispanic or Black, matching the CDC’s nationwide data. More than half of those children live in South Florida, according to the state’s pediatric report. All of the cases are children under 18, with the exception of one 20-year-old man in Brevard County.

Health officials still don’t know why some children develop MIS-C while others do not, and have said additional studies are needed to learn why certain racial or ethnic groups might be more at risk of getting MIS-C and what other factors might contribute to this syndrome. The CDC also told the Miami Herald that there isn’t enough data yet to know if pre-existing health conditions also increase a child’s risk of falling ill with MIS-C.

What can people do to protect kids and at-risk populations?

Bixler believes the pandemic has put a spotlight on where the potential to improve the living conditions of others exists, not just for COVID-19 but for future health issues. She said employers should think about how they can reduce their employees’ risk of infection and what type of sick leave and health insurance they can offer.

Officials should be making sure their messages about masks, hand-washing and social distancing are easy to understand and are “culturally appropriate” for their community, Bixler said, both in visuals and language.

Faith-based organizations should also be using this moment to help protect their congregations by sharing vital information with them, such as where people can be tested, she said.

Bixler and Solano say the best form of protection is prevention. And in the time of COVID-19, the best steps people can take to reduce their risk are the ones health experts have been saying for months:

Wear masks. Wash your hands. Avoid crowded places. Stay at least six feet away from others. Stay home if you feel sick. And don’t be afraid to visit your doctor, regardless of the health issue.

“The fact that we have COVID now does not mean that the world has stopped happening, and that’s what parents need to know,” Solano said. “You need to talk with your pediatrician if you think something is not right with your child.”