HMCS Bonaventure: New Brunswickers remember their time on Canada's last aircraft carrier

Ask Bryce Allen what life was like on aboard Canada's last aircraft carrier and his mind turns back to December of 1959.

Now in his 80s, the Fredericton Junction native was part of the flight crew and had been on board for a little more than a year, joining the crew not long after the Bonaventure was commissioned.

The ship was returning from two weeks of NATO exercises off the coast of Ireland, with four destroyer escorts, when it ran headlong into a North Atlantic storm just north of the Azores.

"The flight deck was 65 feet off the water, and water was flooding the deck," Allen recalls, describing the waves that battered the task force.

Meteorological records from the time show wind speeds of 125 kilometres per hour at the height of the storm, with gusts as high as 166 kilometres per hour.

Allen said, to make matters worse, the elevator for moving aircraft from the deck to the lower hangar had jammed at about a foot below deck level, allowing water to flow down into the ship.

Six twin-engined Tracker aircraft couldn't be moved to safety, and had to be strapped down on deck. All they could do was hope they weren't swept away by the wind and waves.

The upper deck suffered substantial damage in the storm and five sailors were injured.

Allen said he took 8 mm movies of the storm, but "you think I could find what I did with those pictures?."

"Really, the carrier should of sunk," Allen said, "But she came through her."

Gone half a century

It has been 50 years since the Canadian government decided the cost of operating an aircraft carrier was too high to justify keeping the Bonaventure.

The ship was scrapped in Taiwan in 1971.

Allen spent eight years of his life on the Bonaventure, and even though he left the ship in 1965, he said he was sad to see her go.

People who lived in ports like Halifax and Saint John likely missed her too.

HMCS Bonaventure was by far the biggest ship in the navy, and she drew a crowd of onlookers when she sailed into port.

Many Saint Johners of a certain age still remember her arrival in the fall of 1963 for a three-month refit at the Saint John shipyard.

Only carrier purchased by Canada

She was originally designed for the Royal Navy to provide air support for convoys during the Second World War and was to be named HMS Powerful.

But the ship wasn't completed in time to take part in the war, and construction was halted.

After a few years of operating carriers on loan from the Royal Navy, and with increasing Cold War tensions, the Canadian Navy made the decision in 1952 to purchase and complete the Powerful, renaming her HMCS Bonaventure.

Canada's experience with carriers during and after the Second World War had proven the value of carriers for anti-submarine work, and Soviet subs presented the biggest threat to Canadian sovereignty in the 1950s. Plus, the move was seen as a way to help prop up Britain's sagging economy.

She had upgrades to handle more modern aircraft, including a steam catapult to help get enough speed to get airborne, an angled deck to help gain lift and six arresting cables to stop the aircraft during a landing, but the fact remained Bonaventure was 30 per cent shorter than her U.S. counterparts.

Saint John's George Vair wasn't on board during that wild storm in 1959. He was still three years or so away from joining her crew.

But her handling in rough seas was also something clear in his mind.

"One of the problems was she was not made for the North Atlantic," Vair said, "Water would come in around the gun stations in rough weather … not the greatest ship in the world for that sort of thing."

Lines, lines, lines

Vair had been a signaller aboard destroyers before finishing up his stint in the navy on Bonaventure.

The biggest change for Vair was the size of the crew, usually operating with 700 to 800 on board.

"You lined up for everything. You lined up at the galley for meals, you lined up for 'tot' — we still had that then," Vair said, referring to the daily rum ration, a practice that ended in the Royal Canadian Navy in 1972) .

"A lot of people didn't like it because of the lining up."

And it was crowded in the living quarters, too.

"The bunks were set four bunks high on each side. Once you were in, you had about 10 inches to the bottom of the next bunk," Vair said.

"In those Tribal [Class] destroyers, you just strung a hammock, which was a lot better.

"And, you hardly knew anyone outside your own group. Years later, I was sitting in a tavern talking to a guy and discovered we were both on her at the same time."

It also could be a dangerous place to be, especially for the aircrews.

Allen remembers the danger involved in taking off and landing on the small flight deck of the ship the crew lovingly called "The Bonny".

"People from the air force were just flabbergasted," Allen remembers, "'You fly off the Bonny? Jeez, are you crazy or what?'"

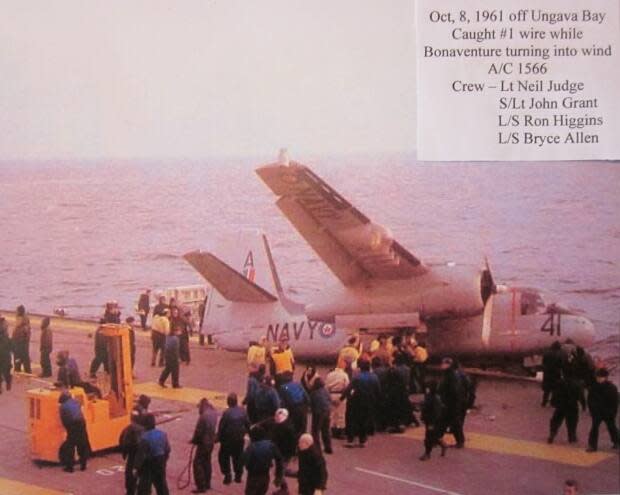

"I only had one crash," Allen said matter-of-factly about a landing in a twin-engined Grumman Tracker.

On a night mission in bad weather, Allen's aircraft made six approaches without being able to get the plane down, so the decision was made to head to a land base in Labrador.

After spending the night on land, they headed back to the ship in the morning, but the weather hadn't gotten any better.

Coming in, the aircraft's arrestor hook missed the first five cables stretched across the deck.

"We caught number one wire," Allen said, the sixth and final cable, and the 10,000-kilogram plane and its four crew members were left hanging off the end of the flight deck, with only the cable keeping it from plummeting into the sea below.

"There were people hollering for us to get out, and people hollering for us to stay inside," he said.

"Finally, I said I've had enough of this and went out [the hatch] right around where the props were, which were still spinning. That was a little bit interesting."

Dangerous business

Some aircrew weren't so lucky.

George Vair was on board for just one year. "We lost two people when I was on it," he said.

And that trip through a hurricane in 1959 ended in tragedy.

Just 240 kilometres or so from Halifax on Dec. 12, after riding out five days of rough weather, a Tracker went into the sea minutes after takeoff.

The newspapers of the day reported the aircraft was launching to take part in exercises with a submarine, just a day before the ship was supposed to sail into Halifax, and that the plane with all four crew members couldn't be found.

Bryce Allen remembers it differently. He said the usual process coming home was to launch the planes offshore and fly into Shearwater air base.

Allen said he was assigned to be on the plane that crashed, but since he was single and it was two weeks before Christmas, he volunteered to give up his spot to a married man.

"The only thing they figured could have happened was that, in a hurry, they threw the baggage in the back of the plane and it wasn't secured. When the catapult launched the plane, they figured the baggage was thrown ahead into the cabin."

Allen said the plane went straight up into the air, and then down into the sea.

'They kept us busy'

HMCS Bonaventure had a busy career, out to sea three times a year, in three-month intervals.

She took part in numerous NATO exercises, sailed as far south as Argentina, and as far north as Ungava Bay. She also had stops in most of Europe's major ports.

She took Canada's first peacekeeping troops to Cyprus, was on high alert during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and picked up victims from a downed airliner off the coast of Ireland.

More than 20,000 aircraft landings took place on her deck, with the last one occurring on Dec. 12, 1969, coincidentally 10 years to the day after the fatal crash Bryce Allen witnessed.

But by the late '60s, the navy was looking to cut costs. And, the Bonaventure, the largest ship in the fleet, was an obvious target.

By that time, Vair was out of the Navy altogether, Allen had moved on to flying in shore-based Argus patrol aircraft. When she was decommissioned, he was there.

Sad to see her go

"It was a bad scene," he recalled.

"She had just had a refit done — $17 million. And they sold her for scrap."

Allen said there has always been a rumour that she ended up in service with another navy, "so maybe she got another 10 years."

There's no proof that's the case. Maybe it's just wishful thinking.

One of her anchors sits in Point Pleasant Park in Halifax, and the ship's bell is at Shearwater's aviation museum, memorials to the last of her kind in Canadian service.