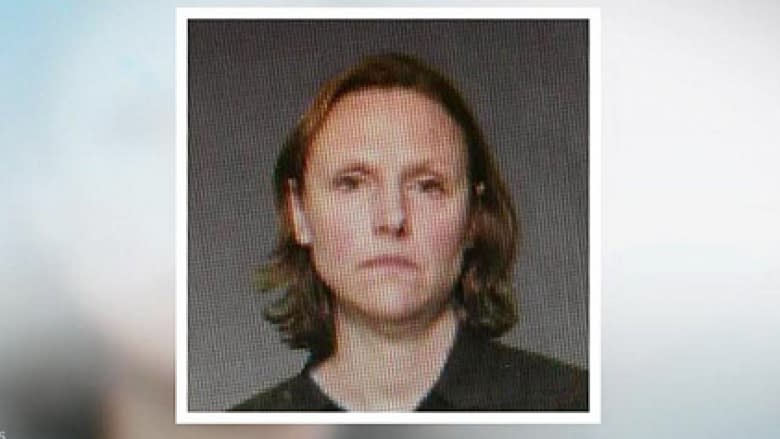

Homicide charges too difficult to prove in Andrea Giesbrecht case, experts say

It's possible the public will never know what led to the deaths of six babies — five boys and a girl — who were found bundled in towels and plastic bags inside a Winnipeg storage locker rented by their mother, Andrea Giesbrecht.

Autopsies gleaned no cause of death and Giesbrecht did not testify at her trial, which concluded Monday.

Manitoba provincial court Judge Murray Thompson found Giesbrecht guilty on six counts of concealing the remains of a child. He also found the six babies were "likely" born alive.

Giesbrecht hid her pregnancies and their births from everyone she knew, concealing their remains in household containers, possibly in an effort to hide the smell of decay, the court heard.

It was only until she defaulted on paying her U-Haul storage bill that employees entered her locker in Oct. 20, 2014, and the crime was discovered. She was arrested later that same day.

Crown made a strategic decision

When discussing the possibility of homicide charges in his decision, the judge said simply that the charge was not available to the Crown because there was no evidence "the children proceeded in a living state from the body of the mother."

The Crown declined an interview after the trial.

Legal experts who spoke to CBC News about the Giesbrecht case offered a consistent take on why there was no homicide charge laid in the 43-year-old's case — without a cause of death or proof the children were not stillborn, the Crown had no choice but to pursue a lesser charge.

Forensic autopsies were unable to pin down a cause of death due to decomposition, and pathologists could not say, with absolute certainty, each of the babies was born alive — although taken together as a group, a leading obstetrician said, it was highly unlikely all were stillborn.

Lisa Silver, a practising lawyer and criminal law instructor at the University of Calgary, said she believes the Crown made a strategic decision to pursue a lesser charge it knew it could prove, as opposed to one that might end in acquittal.

"What strikes me as the initial problem is that causation issue," said Silver of the Giesbrecht case.

"How could the Crown prove that her actions caused the death of these children considering it is possible that one [or more] of them were not caused by her at all but were stillbirths?"

With no clear cause of death at hand, the Crown picked the charge of concealing the dead body of a child, which carries a maximum penalty of two years per count.

"They went with something that they felt they could prove," Silver said.

If a homicide charge were laid against Giesbrecht, infanticide would be the most appropriate charge, said UBC criminal law professor Isabel Grant, based on her knowledge of the case through media reports.

Grant agreed with Silver that the Crown would have had a difficult time proving any form of homicide, including infanticide, without cause of death.

"She has the right to know who she's accused of killing," Grant said. "You can't just say, 'We know you killed somebody.'"

As with all homicide cases, the Crown would have to prove the accused caused the death of a baby, whether directly or indirectly, to prove infanticide.

"[The judge] has to be persuaded beyond a reasonable doubt that they were born alive in order for an infanticide charge to stand," said Grant. "The only thing she would have to do is raise the reasonable doubt that they were not born alive and then she would be acquitted."

Infanticide rare in Canada

Kirsten Kramar, a sociology instructor at the University of Calgary and author of a book on infanticide in Canada called Unwilling Mothers, Unwanted Babies, estimates there are fewer than three cases a year.

"The law itself recognizes there are unique circumstances associated with childbirth and pregnancy. It's necessarily about the baby, but it's about the circumstances in which the mother finds herself," Kramer said.

The punishment for infanticide is a maximum of five years in jail, but according to Grant it's rare for a woman to be sentenced for that long a time.

"Twenty years ago they weren't even usually going to jail," she said.

Giesbrecht is still awaiting her sentencing hearing, which may end up seeing her spend the same amount of time in jail as she would have had she been found guilty of infanticide, said Grant.

Each concealment act was distinct and separated by presumably 10 or 11 months, said Grant, which may lead the judge to sentence her to six consecutive sentences.

"It's quite possible she could get consecutive sentences, which would get her right up to what she probably would have gotten for infanticide," said Grant.