Hunter Biden: do digital platforms care more than News Corp about likely misinformation?

Media organisations shouldn’t publish allegations unless they believe them to be true, after making appropriate checks. This is a normally uncontroversial principle of journalistic practice, reflected in media law. It forms the underpinnings for the social licence to operate that allows journalists access to the powerful and the freedom to deal with confidential sources and leaked information.

Now, that idea is in play on the international stage in a stoush between News Corp and the tech platforms Twitter and Facebook.

It’s a crucial moment in modern media, mainly because the tech platforms seem to be trying to heed the traditional responsibility of publishers, while the world’s most powerful traditional media organisation, News Corp, seems willing to overlook it.

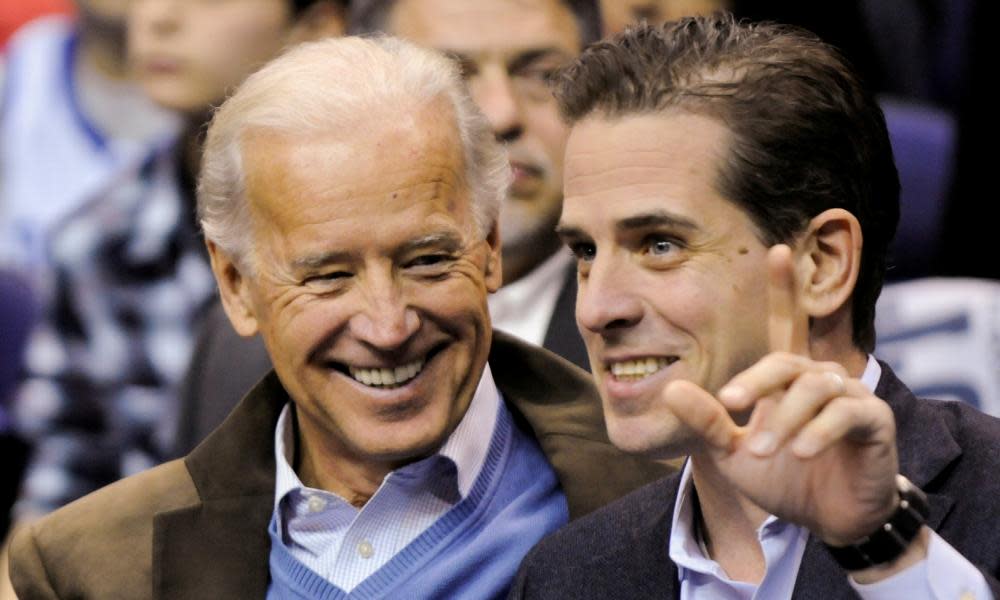

The battleground is a story published in Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post, the essence of which is an allegation that presidential candidate Joe Biden used his previous position as US vice-president to benefit the Ukraine business interests of his son, Hunter.

Related: 'Culture of fear': why Kevin Rudd is determined to see an end to Murdoch's media dominance

The evidence for this is emails claimed to have been found on the hard drive of a computer that Hunter Biden may or may not have dropped at a computer repair shop. The proprietor of the shop gave the hard drive to President Donald Trump’s lawyer, Rudolph Giuliani, who gave it to the New York Post.

There are lots of reasons to doubt the veracity of the emails. Most US media have reported the allegations with a heavy dose of scepticism.

Twitter and Facebook, newly sensitive to the risk of spreading fake news, took steps to stop the New York Post story circulating. Now News Corp has ranged its global journalistic voice in outrage against that decision.

Twitter and Facebook are censors, they say. Yet in acres of commentary on the controversy, there is almost no acknowledgement from any News Corp masthead that the original story may well have been false.

The New York Times reported this week that the Post reporter who wrote the article refused to put their name to it and that other reporters questioned whether the paper had done enough to verify the authenticity of the hard drive’s contents.

Meanwhile, the Washington Post has attempted to fact check the claims and found lots of reasons for believing the story to be misinformation.

More recently, the New York Times has reported that the emails may be an attempt by Russia to influence the US election. This has echoes of the controversy about Hillary Clinton’s emails last election. Meanwhile, Trump’s attempt to dig dirt on Hunter Biden in Ukraine was the trigger for his impeachment.

So the principle of fact-checking and taking care to publish the truth could hardly be more important, and more consequential.

But much of News Corp Australia’s reporting of the controversy seemed reluctant to consider the possibility that it was misinformation.

A few examples: the Daily Telegraph’s Sharri Markson told Channel Seven’s Sunrise this week that Twitter was “playing a political role in the campaign” by restricting the story’s circulation.

She said Twitter and Facebook were “ending the free press” and were “like state media in China”. But no acknowledgement that perhaps the original story was false.

In The Australian, the foreign editor, Greg Sheridan, has described the decision of Twitter and Facebook to “outright censor” the “exclusive revelation” as “the most shocking breach of democratic norms the US has seen in decades”. Again, there was no acknowledgement of the doubts about the story.

Singing from the same song sheet, The Australian’s Washington correspondent, Cameron Stewart, accused Twitter and Facebook of showing political bias in their “relatively new notion of intervening to limit political disinformation … So far, the censorship axe appears to be falling only on one side of politics, the conservative side.”

He went on to compare the Post story to the New York Times publication of Trump’s tax returns – which was freely circulated on Twitter and Facebook.

“If tech giants are going to take the sweeping step of censoring political stories published by mainstream media, they must be willing to censor both sides of politics if they want to be seen as impartial.”

That would be fine if it weren’t for the simple fact that one story is likely false, and the other’s truth has not been disputed – indeed, its accuracy has been implicitly confirmed by Trump.

Surely that matters? Surely, even if you think Twitter and Facebook should let the story circulate, you should acknowledge that there are doubts about whether it is true?

The context to all this is even more consequential.

A source in the Australian government said to me recently that when it came to fights over media, a stoush between the tech giants and News Corp might amount to a “fair fight”.

This is despite the fact that Google, to pick just one, dwarfs News Corp in both reach and revenue.

But News Corp has the political influence, and right now is in the front line of a number of battles with the tech giants.

In Australia, there is the battle over the government’s plans to introduce legislation to make Google and Facebook pay for using news media content. That plan is backed by most media, but News Corp has been in the forefront of the campaign.

Meanwhile Google, Facebook and Twitter have always, until now, rejected the idea that they are a kind of publisher, and therefore should be subject to the same kinds of disciplines and accountabilities that normally apply to the news media.

As the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission said in its Digital Platforms Report, although the digital platforms don’t directly produce journalism, they do perform key roles in the supply and consumption of news.

Like traditional media organisations, they publish, market and monetise content. They collate and curate news. Through their algorithms, they influence who consumes what news. These are hugely important functions. Around 43% of Australians use online platforms as their primary source of news.

The Hunter Biden-New York Post controversy has dragged the digital platforms into an implicit acknowledgement that they perform some of the functions of traditional news organisations and have similar responsibilities. They have made editorial decisions about what is and is not true – what should and should not be circulated. They have heeded the foundational principle of journalism.

It’s a big shift. And, given their record, there are plenty of reasons to be cynical about the tech giants’ role in misinformation.

The strange thing is that right now, they seem to care more about checking veracity than News Corp – the world’s most powerful traditional media organisation.