Indigenous people fear mother languages may 'disappear' in Windsor-Essex

With less than one per cent of the Indigenous population in Windsor-Essex speaking their mother language at home, some are taking it upon themselves to ensure the dialects don't disappear altogether.

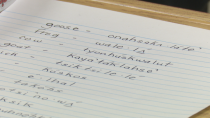

Many people must start from the basics by learning how to identify colours, animals and introduce themselves.

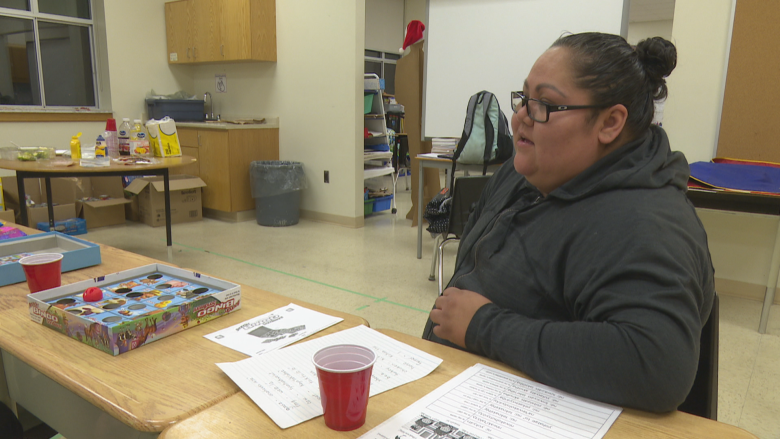

Evangeline John, a Grade 12 student at École secondaire E.J. Lajeunesse in Windsor, hopes she'll soon be able to have full conversations in her cultural language — Oneida.

The 17-year-old attends night classes with her family put on jointly by the area's public and Catholic school boards.

Her worst fear is that the language will be forgotten.

"That's the main reason why we're going here because we are worried and we want to make sure that this language doesn't die out," she said before a recent evening class. "Once the language dies, the culture dies."

John isn't alone in being unfamiliar with the language of her ancestors.

Most Indigenous people can't speak native language

Of the 9,870 people who identified as Aboriginal in Windsor-Essex for the 2016 census, only 55 of them said their mother tongue was an Indigenous language. Even fewer said they spoke the languages at home.

The trend of declining Indigenous languages doesn't stop in southern Ontario, it carries on throughout the country. The number of people in Canada who spoke an Aboriginal mother tongue dropped from almost 26 per cent in 1996 to 14.5 per cent in 2011.

To combat the "staggering" numbers, language instructor Sasha Doxtator used a special version of bingo to teach her students different types of animals in Oneida. She leads that class and another course for the Ojibway language every Thursday night for both Catholic and public school students, as well as their families.

Languages help with identity

Learning the language helps people with their sense of identity, she said — especially for those in Windsor-Essex who are away from their home community.

"It's very important that we have our language because it's who we are. It's our identity, it's our traditions, it's our ceremonies. It ties into everything," Doxtator explained.

She admits to being far from fluent, but is one of the few who knows enough to teach others the language. Taking classes at the Oneida Nation of the Thames Monday to Friday is helping to hone her skills, but her grandmother may be the most helpful teacher of all.

She's one of roughly 30 people whose mother tongue is Oneida, which is why the language is considered endangered.

Oneida grandmother known as the 'dictionary'

"They call her 'The Dictionary,'" Doxtator said with a smile. "She's one of the ones who knows a ton of words and still speaks it fluently."

Indigenous languages were mostly taught orally, with very few of the words and pronunciations documented anywhere. Doxtator now passes along the dialect to her young daughter, with hopes it will trickle down through the generations.

Much of the decline in Indigenous languages can be traced back to the residential school system and the Canadian government's plan in the 19th century to diminish or abolish the traditions of First Nations.

The government believed Indigenous people's best chance for success was through learning English and adopting Christianity.

"They did what they could to take away our language from us," said Doxtator. "It's all about us finding our strength and getting back our languages."

New language courses coming

There's some momentum locally in trying to revive the many languages that appear to be disappearing. The Caldwell First Nation in Leamington recently received funding to offer its own class. The Can-Am Indian Friendship Centre in Windsor is also currently revamping its language courses.

But some institutions, including the University of Windsor, still aren't offering any classes for Indigenous people to expand their native vocabulary.

Although the university has an Aboriginal Education Centre, the school doesn't have any Indigenous language offerings. Neither does St. Clair College.

Language courses are something Evangeline John wishes she would see more often off reserves. She's taking much of next year to head back home to take language classes with the goal of becoming fluent.

John also said it's important to learn from elders before they die, taking with them their vast knowledge of the language.

School board can't justify Indigenous day courses

Officials with the Windsor-Essex Catholic District School Board said they would like to offer Indigenous language courses during the day — so students don't have choose between after-school sports and learning Iroquoian languages — but with just 200 students who identify as Indigenous in the local Catholic school system, it's not practical.

"It's really difficult to offer languages during the day," said Darlene Marshall, Indigenous Education Lead at the WECDSB. "You would only be doing it for one or two students at a school, depending on where you were."

Language classes a family affair

Marshall, a member of the Caldwell First Nation, became the Catholic school board's first person to fill her newly-created position In September.

Since the passing of Marshall's father more than 20 years ago, what little of the language she learned from him has been lost.

To help regain the knowledge, she attended the school board's first Ojibway after-school class of the semester with her eight-year-old grandson.

"We hope to revitalize the language and be able to pass that on to our next generation," Marshall said.

The Canadian government is also in the process of developing legislation with Indigenous peoples that will be used to protect the up to 90 Indigenous languages in 2018.