Indigenous woman's eviction highlights grey areas in divorce cases

A woman on the Wahta Mohawk territory is getting kicked out of the home she built with her ex-husband without receiving a settlement she said is owed to her.

"I'm in a situation where there isn't equality when the breakdown of a marriage happens," said Tori Cress.

The federal government changed divorce and separation rights for those on reserves in 2014 but the 41-year-old Cress claims those laws aren't being respected on the reserve near Muskoka, Ont.

The Ojibway and Pottawatomi member of the Beausoleil First Nation moved to the Wahta Mohawk territory 10 years ago, where she eventually met her future husband Neil Schell while working at a tobacco shop.

They built a house at 2289 Muskoka Rd. 38 in 2007, a plot of land to which her husband's great-aunt held a certificate of possession – similar to a deed, off reserve.

Cress said they built their dream home, carefully selecting details for the 2,200-square foot home, where they would have no rent or mortgage.

The couple moved in together in 2008, with her two children, and got married the following year.

But the marriage fell apart. They separated after just a couple of years and eventually divorced in June 2014.

Provincial law on notice not in effect

Not long after the divorce, Schell's father, Lawrence, purchased the certificate of possession for the land from his relatives.

Cress and her children continued to live in the house. She had no claim to the land through membership in the local band, but believed she still had a marital claim to the buildings on the lot.

Cress was told she had to leave the property without receiving any share of the assets in November 2016.

"I wanted to fight for my house because I built it, and why should they be unjustly enriched?" she said.

Lawrence Schell, who is in poor health and wanted to get his affairs in order, had his lawyer Trisha Cowie issue a notice of eviction.

The notice stated there was no lease agreement in place, no rent being paid and Cress was not "a member of Wahta."

"Essentially, you have been able to occupy the Property based on the generosity and good will of Mr. Schell," the statement read.

Since the property is located on reserve land, Schell — who also sits on the band council — had no requirement to abide by any Ontario laws to give notice.

Cress was told "to vacate the property" in two days.

Reeling, she immediately got an injunction to postpone the move until March 31, 2017 and also learned about the Family Homes on Reserves and Matrimonial Property Act, which came into force in December 2014.

Cress believed the act was supposed to dramatically change the rights of spouses on reserves when they split up, especially if either of them was from a different band.

"Prior to this it would have been, 'pack up your stuff.' You would have been band council removed with no claim to anything," she said. "I was fearful that that's what would happen to me."

Mediation process ongoing

She's moving out without a settlement of the couple's joint assets, namely the house, so she's in a legal battle that's in settlement mediation in a Superior Court of Ontario in Bracebridge.

"I think Canadians need to be aware of what's actually happening on reservations," Cress said. "There's so many people like myself that are out there fighting these small battles."

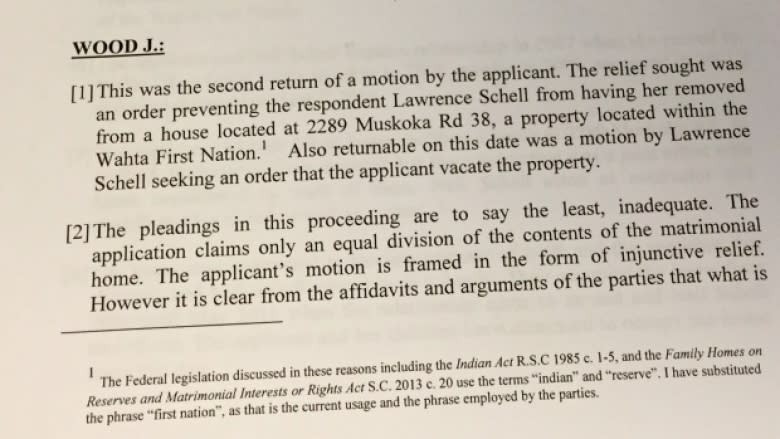

In response to her court appeal to prevent the eviction, Ontario Superior Court Justice T.M. Wood wrote of the intricacies of a number of laws converging in this case.

For example, Cress can't stay on the property on a permanent basis as only members of the Wahta First Nation can get occupants permits for land on that territory.

Cress must leave the property, especially since the two separated years ago, however, "the issue of possession of a house located on First Nation land is not a straightforward one," Wood wrote.

He referred to the 2014 act as "remedial legislation creating rights that didn't exist before," and added, according to the new act, the couple didn't need to have a certificate of occupation for the land the house is on.

The presumption was that some residences are temporary or "movable" which is "a reality of land occupation of many First Nations," according to the court document.

Bev Jacobs, the former president of the Native Women's Association of Canada, was consulted in drafting the act.

"The process was supposed to allow those divisions of assets, so that a person like Tori Cress wouldn't be left out in the cold," Jacobs said.

'Humanity comes into place'

She said in the past it was "up to the band council to determine who gets a home on the reserve."

With the 2014 legislation, Jacobs said even if Cress or others like her are not members of the local band, "the humanity comes into place."

It's crucial, she said, to ensure "there isn't homeless mothers and children that end up in the most vulnerable places once they do leave their communities."

Trisha Cowie, Lawrence Schell's lawyer, said, "In this case we're talking about the legislation and how it's going to be applied retroactively — if it should be at all —which I think will have a very large impact on many First Nations."

Cowie, who is a member of the Hiawatha First Nation and was also a federal Liberal candidate for Parry Sound-Muskoka, explained "we're seeing more of those Family Law act principles being applied now on reserve with this new legislation."

Having said that, she said the position for her client is cut and dried – that Lawrence Schell has no obligation to Cress as the certificate of possession holder for the land.

But there's still the question of settling the assets — as would be typical if this was assessed through Ontario's Family Law Act — and then how that value is assessed.

Neil Schell's lawyer declined to comment on the case.

Wood has scheduled another settlement conference for May 8, 2017 in the hopes the parties can come to an agreement without his intervention.

Cress will be moving on with her adult child who has a disability. Another adult child will be finding a place to live elsewhere.

With 644 bands in Canada, Cress feels she's not alone in a fight like this one.