Indigenous women nearly 10 times more likely to be street checked by Edmonton police, new data shows

Critics are calling for an Alberta-wide ban on street checks as a CBC News investigation reveals Edmonton police have been disproportionately stopping, questioning and documenting Aboriginal and black people in non-criminal encounters.

The data, obtained by CBC News from the Edmonton Police Service through a freedom of information request, shows that in 2016, Aboriginal women were nearly 10 times as likely to be checked as white women.

The same year, Aboriginal people were six times more likely than white people to be stopped by Edmonton police. Black people were almost five times as likely as white people to be stopped.

(CBC is using the term Aboriginal as reported by police and Statistics Canada, instead of Indigenous).

Edmonton police say street checks play an important role in solving crimes and insist stops are not racially motivated.

"It's racial profiling — just full stop," said Bashir Mohamed of Black Lives Matter (BLM) Edmonton. The group is calling for an end to street checks, which are also commonly known as carding, and the destruction of the data collected by police.

"Within the black community, people have known that this has been happening and the numbers just prove what we already suspected."

The BLM position is supported by the Edmonton-based Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women and Progress Alberta, the advocacy group involved in the release of data last week that showed black and Indigenous people in Lethbridge are disproportionately carded.

Over the past two years, the practice, which also includes vehicle stops, has increasingly come under fire in Edmonton from lawyers, human rights advocates and Indigenous leaders.

"We are in support that carding should be banned," said Rachelle Venne, CEO of the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women. Venne sits on the Indigenous Community Advisory for Edmonton Police.

Her group runs programs to remove barriers faced by Indigenous women who are disproportionately affected by discrimination, violence and overrepresentation in the justice system.

"As they rebuild their lives, those type of instances of carding really set them back emotionally," Venne said, explaining some clients complain of "big brother kind of looking down at them."

Venne,said she hopes the Edmonton police data prompts discussion about whether street checks are based on safety concerns or the possibility of racial profiling. "Unfortunately, a lot of work we are doing is pointing towards that."

Venne said she's never been carded, but many of her family members have. "It's very hurtful. It's hurtful because you wonder, 'Why me?' "

Edmonton police Staff Sgt. Warren Driechel said street checks aren't racially motivated. Officers are trained to conduct them appropriately and respect individuals' rights.

Few instances of bias, police say

"I can't say in every instance that a street check has never been initiated on that," said Driechel, who is with the intelligence branch. "But from what I can see through our audit process we found very, very few instances of any kind of street check or anything that may even be construed as bias."

Driechel said he doesn't believe the data is "truly representative." For instance, there is no field in a street check report to enter race. Officers enter it in another report, based on their perception, but it isn't mandatory.

Many times the ethnicity is left blank or multiple races are recorded. That complexity also presented many challenges for analysts when CBC News first requested data on race a year ago.

Patrol officers are much more proactive in areas of the city affected by crime, Driechel also noted.

"So by focusing more police activity that's more proactive into that smaller area we could end up seeing a higher rate of certain ethnics."

Numbers dropped after CBC investigation

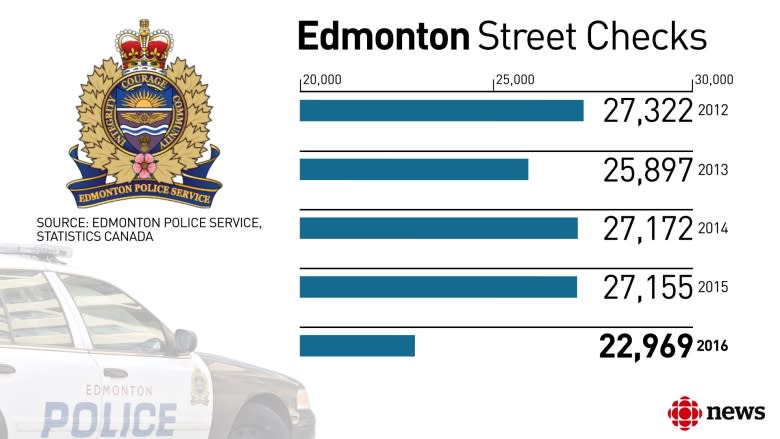

Between 2012 and 2016, Edmonton police stopped, questioned and documented 130,515 people when there was no grounds for arrest, performing an average of 26,103 street checks per year.

But EPS records show the number of stops has declined significantly since a CBC Edmonton investigation in September 2015.

In 2016, the number of street checks dropped to 22,969, a trend that appears to be continuing. In the first three months of 2017, Edmonton police conducted 4,682 street checks.

Driechel said during a review conducted in 2016, police realized officers were recording non-street-check incidents such as minor investigations, but have since narrowed the scope.

While Driechel emphasized that street checks are essential for community engagement, intelligence gathering, future investigation and the prevention of crime, he said police have also made significant changes to their policy and procedures.

More oversight for street checks

Among those changes, all street check reports must now be cleared by a supervisor who has been trained to check for bias. Officers must be able to articulate why they conducted the stop and police will conduct twice-yearly audits, he said.

But Driechel said the EPS is waiting for direction from the province, before making to changes to the retention of street check data, which is kept indefinitely. Alberta Justice formed a working group last year to develop provincewide street check guidelines and plans to conduct community consultations in the near future.

"Responsibly, we would only keep this data for so long," said Driechel, adding over a period of time the content is no longer relevant. "We don't want to become prejudicial by reading the street check 10 years from now and saying that this person was involved in this lifestyle."

CBC News has obtained a copy of the street check policy through a freedom of information request, clarifying the rights of those being stopped in Edmonton for the first time.

"Members must be aware that the subject[s] is not obligated to provide any information during a street check, and may disengage with members at any time," states the policy. "Members must be able to articulate this to the subjects[s], and should be able to reinforce that the subject[s] is not under detention if questioned."

'Not community engagement'

But critics say many people are not aware of their rights, or may be hesitant to exercise them.

"If you're young, you don't know your legal rights," said Mohamed. "If you grew up in that police environment you kind of fear walking away because you wonder what's going to happen. You automatically assume you're detained."

Mohamed recalled his own carding experience in junior high in Edmonton. He and his friends were stopped on their way to the corner store and said that after that, whenever he saw a police cruiser, he felt uncomfortable.

"I know they're there to protect and serve but it just mostly felt like they were just watching us," said Mohamed, adding the constant harassment by police leads to fear and a breakdown of trust.

"This is not community engagement," he said. "If the police really want to do community engagement then they can bring out a soccer ball."

EDITOR'S NOTE: Population statistics used for this story are based on the latest census data from Statistics Canada's 2011 National Household Survey. The number of cardings and the race of individuals was obtained from Edmonton Police Service records.

If you have a street check experience you would like to share, please send the information to newsedmonton@cbc.ca