Inquiry into racism in B.C. health care must hear from two-spirit people, nurse says

"Is that booze or hand sanitizer I smell on you?"

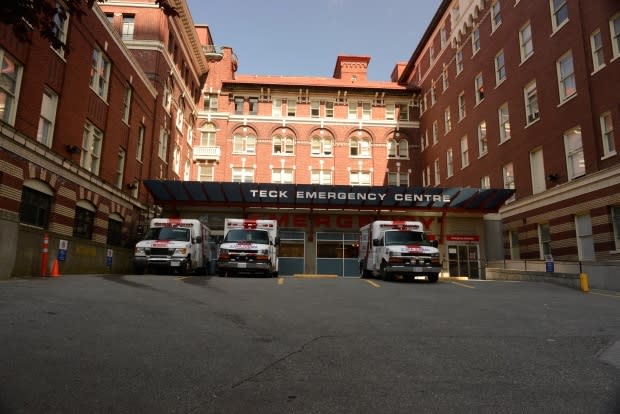

This is the question Tyler-Alan Jacobs, 35, says a health-care professional at St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver, B.C., asked while Jacobs was seeking medical help during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A two-spirit fashion designer and member of the Squamish Nation, Jacobs says, unfortunately, this was not the first time racial discrimination factored into a situation concerning Jacobs' health.

In June, the province launched an investigation into systemic racism in the health-care system in light of allegations health-care staff in emergency rooms were playing a "game" to guess the blood-alcohol level of Indigenous patients.

Now, Jessy Dame, a Métis two-spirit registered nurse who says he has witnessed similar racism first-hand is calling on other Indigenous LGBTQ patients like Jacobs to come forward and have their stories included in the inquiry.

To have their stories included, Indigenous people must complete an online survey about their experiences accessing care by Aug. 6 at 4 p.m. PT.

Impact of discrimination

Dame, who works as a nurse at an LGBTQ-focused sexual health clinic in downtown Vancouver as well at St. Paul's Hospital's neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), says bringing more stories of lived experience to the forefront is the only way to enact change.

"We see an increase in depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts and gender dysmorphia related to acceptance [by] health care-providers," said Dame on CBC's The Early Edition.

The Canadian Public Health Association said in 2018 those who experience racism "exhibit poorer health outcomes, including negative mental health outcomes, negative physical health outcomes and negative health-related behaviours."

Dame said he has experienced racial discrimination at walk-in clinics in the Lower Mainland and at hospitals, adding that when two-spirit people are treated in such a fashion it can keep them from seeking medical help in the future.

Jacobs remembers waiting for a pre-scheduled medical appointment and watching non-Indigenous patients being prioritized. Jacobs said in those situations, getting upset with staff often means the Indigenous patient is perceived as the hostile "bad guy."

"We are people. We bleed the same. We breathe the same air," said Jacobs, adding it makes people wary of even asking for help.

More betting games

Dame said racial discrimination in health care can begin in the education system and that this needs to be addressed so new nursing students are not exposed to old racial ideas.

He said when he was studying nursing he was taught Indigenous patients have a lack of emotion.

Dame graduated in 2015 from Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, B.C.

After entering the workforce, Dame said he witnessed colleagues betting on how many pregnancies young Indigenous mothers in a postpartum maternal unit had already had.

This he said, is only one example of on-the-job racism he has seen levelled at Indigenous patients.

"It took me a long time to stand strong and stand up and say this isn't just a joke, this has been going on for far too long and people are dying all the time because of this racism," said Dame.

Hold your head high

Mary-Ellen Turpel-Lafond, a former judge and longtime children's advocate in B.C., has been appointed to lead the investigation and make recommendations to the province.

Dame said he is hopeful that this process will deliver some healing to those who have been wronged.

Turpel-Lafond has said she will present recommendations stemming from her investigation within months.

But Jacobs has some recommendations to share with two-spirit people now: "Walk with your head held high," said Jacobs, "And if you're not getting the right help ... look toward our community."

To participate in the survey concerning Indigenous racism in the provincial health care system, tap here.