Labour must not ignore BAME base in rush to rebuild red wall, activists warn

Unmesh Desai was 17 when workers at the Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories in Willesden, London, went on strike in 1976. His mother, who had come to the UK from Tanzania and worked in a factory in Huddersfield before moving to the capital, was friends with many of the plant’s mostly female east African Asian employees.

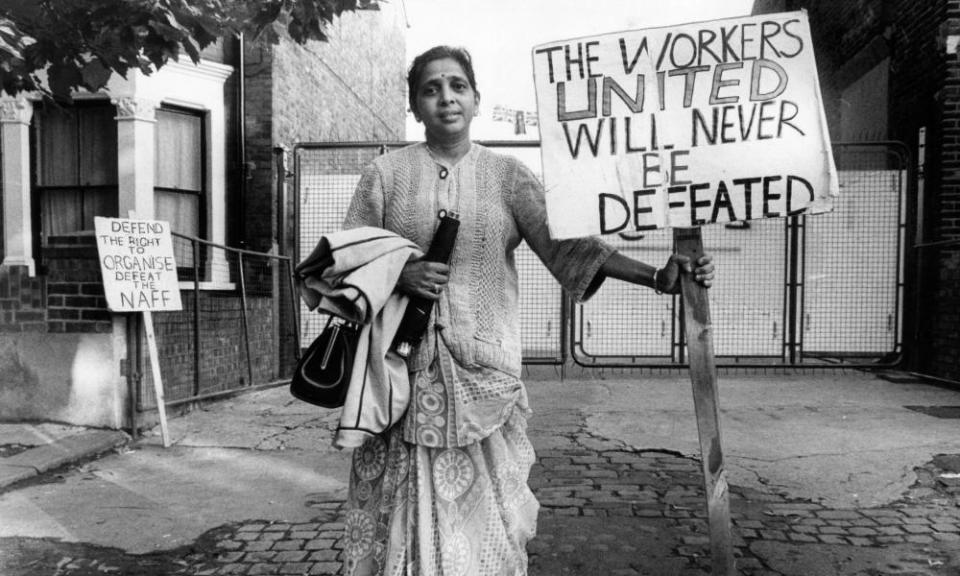

The Grunwick dispute – which saw its participants dubbed “strikers in saris” by the media – lasted two years, with 550 arrests. “The back of the house overlooked the picket line, so there was no question of whether or not to support the strike. It was literally on our doorstep,” said Desai, who is now a London assembly member for the city and east constituency.

Desai, who became a Labour councillor in Newham in 1998, described the dispute as marking the beginning of his political awakening. He remembers the miners travelling from Yorkshire to join the picket line and support the striking women – two parts of the Labour movement coming together in their shared interests. “They are such iconic images,” he said. “Asian women, very short in stature, with all these Yorkshire miners. There were hundreds of people there.”

In the wake of Labour’s crushing election defeat, the apparatus that supported that alliance appears to be hanging by a thread. In the postmortem that followed the loss of seats across the so-called “red wall” of de-industrialised areas in the north of England and the Midlands that had voted Labour for generations, one idea has gained traction: that the party has lost touch with its “traditional base” of white working-class voters by pandering to the metropolitan elite. In that conversation, many fear, another part of Labour’s “traditional base” – the working-class black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) voters living in seats that are every bit as much a part of Labour’s “heartland” as the red wall – has been forgotten.

“The question is, what are Labour heartlands?” said Rohit Dasgupta, an academic and Labour councillor in Newham in east London. “Is it just places like Bury and Hartlepool, or is it also places like inner London boroughs, like Newham and Hackney? These are also Labour heartlands. Lots of Labour’s core vote comes from here, and there are sizeable BAME communities who vote Labour. I think it feels almost like some people within the party take the BAME vote for granted.”

Dr Zubaida Haque, deputy director at the race equality thinktank the Runnymede Trust, argues that in their desperation to find a way to win back the red wall, some in the party risk falling for a rightwing narrative that pitches white and BAME communities against each other. “The right have put forward the argument that the reason white working-class people are being neglected is because advantages and privileges and focus and attention have gone on ethnic minorities,” she said.

“But that’s not the case. All working-class interests, white and BAME, have been neglected by politicians. In fact research has shown that ethnic minorities have lost out from austerity policies much more, in the same way that women have lost out more in comparison to men. The economic problems of white working-class groups in the north are not due to migrants or to black and ethnic minority people; one group has not lost out at the expense of the other,” she said. “It’s not a zero-sum game.”

The debates surrounding the Labour leadership race have so far focused on the question of which candidate would be best placed to win back support from white working-class communities, with many arguing that the next leader should be a northerner. Pundits responded to the rumour that the Tottenham MP David Lammy could run for leader by suggesting he would not be the best person to reconnect with the party’s “patriotic heartlands”. In all of this, some activists have argued, Labour risks repeating the mistake it made with those “red wall” seats with the places that now form its last stronghold.

Faiza Shaheen, who runs the thinktank Class (Centre for Labour and Social Studies), was Labour’s candidate standing against Iain Duncan Smith in Chingford and Woodford Green. “It’s true that we’ve neglected those areas [in the Midlands and the north], but the way forward isn’t then to neglect working-class ethnic minorities. It’s actually to tell the story of how we do share a lot of the same life experiences.”

Researchers from Class conducted focus groups with nearly 80 people in London and found “significant overlap in everyday lived experiences” of white working-class and minority ethnic or migrant working-class people. The four main themes were a feeling of a lack of power and a voice; concern over the precariousness of their living conditions; experience of class and race prejudice; and a resentment at the loss of community space.

“We saw those four common themes regardless [of background], so we need to be more sophisticated in the way that we treat the working class, and we need to tell a better story and bring people together, because ultimately, if you pit white working class against immigrant or ethic minority working class, you’re not going to solve anything,” said Shaheen.

While Will Jennings at the Centre for Towns thinktank is clear that Labour’s loss of support in certain white working-class communities is a problem the party needs to address if it is ever to achieve power again, he said that did not mean it should disregard other parts of its coalition.

“We haven’t seen yet the data from the British election study, so we can’t be absolutely sure how people voted, but we do know that Labour’s vote tends to do better in areas with more ethnic minorities,” he said. “You can’t get around the fact that Labour has seen its vote fall most sharply in areas that were leave voting and, by composition, had fewer ethnic minorities.

“Labour should be concerned about why it lost support in those places and the feelings of economic distress felt in those places – people being discontented with politics and concerned by social change – but that doesn’t mean that it should disregard other parts of its electoral coalition.”

The focus on the “left behind”, white working-class community that voted to leave the EU also ignores the fact that many BAME people also voted for Brexit, said Haque. According to polling, 32% of BAME voters voted to leave – 33% of Asian people, 27% of black people and 30% of Chinese people.

Many of them also live in the constituencies that are at the heart of the discussion. “The erasure of ethnic minorities in the north and Midlands is quite astonishing,” said Haque. “In many constituencies you wouldn’t have got that Brexit vote if it wasn’t for ethnic minorities also voting Brexit.

“They talk about a select number of areas like the Bolsovers and the Sedgefields and the Bishop Aucklands, but they’re not talking about the Oldhams, the Bradford Easts, the Stoke-on-Trents. They have a substantial number of ethnic minorities, but they just get erased. People just talk about the white working-class Brexit voter.”

Polling conducted by Opinium during the general election found that Labour was leading the Conservatives by 25 points among black, Asian and minority ethnic voters, with more than half (52%) saying they could imagine Jeremy Corbyn in Downing Street.

However, those figures mask a decline in support for the party among certain communities, said Desai. “For various reasons British Indians have been alienated,” he said. (A YouGov survey of British Indians, conducted in November, found that their support for Labour had fallen by 12 percentage points since the 2012 election – from 46% to 34% – in part because of Labour criticism of India’s ruling BJP party.) “The Jewish community has been alienated too, for reasons that have been widely publicised,” he said, referring to the party’s antisemitism crisis.

Desai said he often thinks about an experience his mother had two days into her job working in a factory in Huddersfield. “It was the first time she had seen snow and she had a bad fall. The largely white female workforce came running out to help. They made her a hot drink and clubbed together to get a taxi for her to go home, saying they would explain to management what had happened.

“There was quite a lot of racism in west Yorkshire at the time, but that showed the commonality of the working class. My mother still remembers that incident to this day.”