Lalia Halfkenny: an important history almost lost to time

Lalia Halfkenny was the first Black New Brunswick woman to graduate from an institute of higher education at a time when few Black Canadians had access to any schooling at all.

Halfkenny was the only Black graduate in her class at the Acadia Ladies Seminary in 1889.

Theresa Halfkenny, who believes she is likely a descendant, said stories of accomplishments like Lalia Halfkenny's need to be kept alive.

"When we first found out and heard about it, we were like, 'Oh my gosh'," she said.

Like Lalia, Theresa is from Dorchester. She moved to Amherst, N.S. years ago, where she still lives.

Halfkenny is on the board of the Cumberland African Nova Scotian Association, where she focuses on cultural education. She helps to organize cultural events, and speaks in schools stressing the importance of valuing and sharing history.

"There's so much here that is so rich," she said. "Those of us that are involved in trying to keep this alive, it's been a little bit difficult because sometimes it's hard to get the youth to come on board with it."

But Halfkenny said there is a renewed interest in Black history since conversations around anti-black racism have become part of mainstream conversation.

"It's so important that we do that for our youth, but then it's also important that we do that for others in the community."

She said everyone is worse off when Black history is erased from the history books.

Halfkenny said she wasn't aware of Lalia Halfkenny's achievements until about ten years ago.

That's when her story was rediscovered by Jennifer Harris, professor of English at the University of Waterloo. She encountered Lalia Halfkenny's name when she was researching historic Black families in the Sackville area.

Because it's such a distinctive name, Harris started tracing the family.

"I came across this reference to a Lalia Halfkenny in an educational context and I was surprised because I'd never heard of her," said Harris.

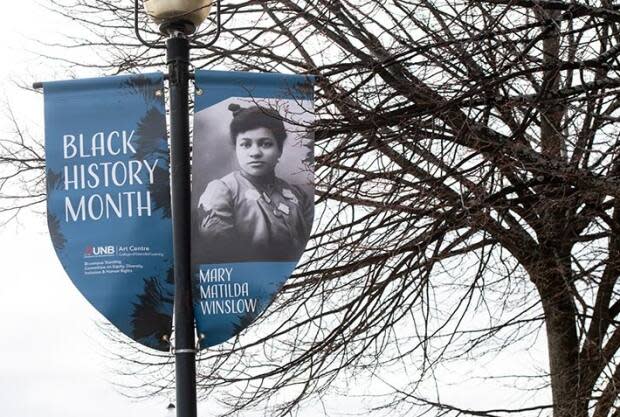

Other prominent educated Black families like the Winslow sisters who were the first women to graduate from the University of New Brunswick and Edwin Howard Borden, the first Black Nova Scotian to graduate from Acadia University had been written about, but not Halfkenny.

"I wanted to know more," said Harris.

After two years of pouring over microfilm, writing to archives and ordering records, she'd put together a story that seems to have gone untold for decades.

Lalia Halfkenny was born to an unwed mother in 1870 in the Sackville area. Soon after, the family moved to Dorchester to live with relatives.

Despite Lalia's difficult beginnings, the Halfkenny family had a reputation as skillful stonemasons.

"They traveled and built all kinds of fabulous buildings in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Maine," said Harris.

Little access to education

At the time, schools in New Brunswick were segregated, often denying Black children access to an education.

According to Harris, in Dorchester, "it was a little bit easier for Black New Brunswick families to get into the school system for a whole host of reasons."

In her research Harris found that Dorchester was better of financially than many communities and it's possible the Halfkenny's reputation as skilled labourers gained them access.

Whatever the reason, Harris said under the circumstances, for Halfkenny to continue on to Acadia Ladies Seminary, "she must have excelled."

Harris said family support played a major factor in Halfkenny's schooling.

It's who you know

"Lalia Halfkenny probably got to go to the Acadia Ladies Seminary because her great uncle Yates Hamilton was the janitor," said Harris.

"He was the much beloved janitor who had a wonderful relationship with the president and he sponsored her."

Having a member of her family at the school most likely gave her access to education other Black families would not have had.

Harris said proof of Halfkenny's academic excellence was found in newspapers of the time, that talked about her giving talks in Halifax.

She wanted to continue her education at the Boston School of Elocution, but didn't.

"I suspect it was a funding issue," said Harris.

Ushered into the kitchen

Instead, Halfkenny looked for work.

"What we know is that for Black women of a certain level of education in the 19th Century in New Brunswick, it wasn't easy," said Harris.

She refers to a quote from Mary Matilda (Tilly) Winslow, who graduated from UNB a few decades after Halfkenny.

"Whenever she went to apply for a job, she was ushered into the kitchen," said Harris.

"This is someone who'd been top in her class and she just kept being taken to the back."

Like Winslow, Halfkenny went on to find success in the United States, working in Virginia as a teacher.

Tragic end

Halfkenny's life was cut short when she died at the age of 26, most likely of consumption.

Harris said the trail blazer volunteered in a home for African American families who were living in poverty.

"It seems quite likely she contracted something there and died relatively young."

Her early death is another reason why Halfkenny's story may have faded for a time, but Harris says her death didn't go unnoticed.

Records show that her students showed up at the train station and sang as her coffin was loaded aboard.

"Which is heartbreaking," said Harris.

Halfkenny's body was returned to Nova Scotia, "where there was a recognition of her life and her contributions."

"She was very much a valued and beloved individual who made a difference in people's lives, even in such a short time frame," said Harris.

Harris continues to study Black history in the Maritimes, but said there are others doing important work too. She notes Harvey Amani Whitfield at the University of Vermont and the founding director of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design's Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery, Charmaine Nelson.

Theresa Halfkenny said she's glad the work is being done to rediscover, and preserve the region's rich Black history.

She's doing her part as well on a small scale with her own children and community, by putting a together a history of her own life.

"I notice there are pieces of history that even I never shared with them, and so now they're asking questions," said Halfkenny.

"I do believe we all have a story to tell and we all have something to offer and we always have things that were done that did contribute to the communities that we live in."