Learning to live after a loss of faith: why some may back away from religion

David Richards came from a deeply religious background. He taught Sunday school and served on his church's board of directors, and had been a peer chaplain in university.

But after years of questioning his beliefs, Richards — who grew up in what he described as a conservative, evangelical household — had to admit to himself that he was no longer a man of faith.

It wasn't an easy thing to accept, he says.

"The thought of no afterlife was a very scary thought," he said. "Eventually it just came down to 'just because something is scary doesn't mean it isn't true.'"

Richards is one of a growing number of people throughout Saskatchewan and Canada who describe themselves as having no religious affiliation, according to Statistics Canada data.

His journey to "non-believer" came with difficult realizations, he said

The idea that someone could do "truly, horrific, evil things in life" and not be punished also gave him anxiety.

"On a visceral level, that thought sucks. That's an awful thought," Richards said. "Even if we recognize the world isn't fair or just, we want it to be."

Atheism has risen

During the last national household survey (NHS) in 2011, Saskatchewan had 246,305 residents who identified as having no religious affiliation, which was more than 23 per cent of the provincial population for that year. That's a significant jump from the 2001 NHS, when just under 16 per cent — or 151,455 people — said they had no religious affiliation.

Similar rates appeared at the national level, with nearly 24 per cent of Canadians identifying themselves as having no religious affiliation in 2011 up from from 16.5 per cent in 2001.

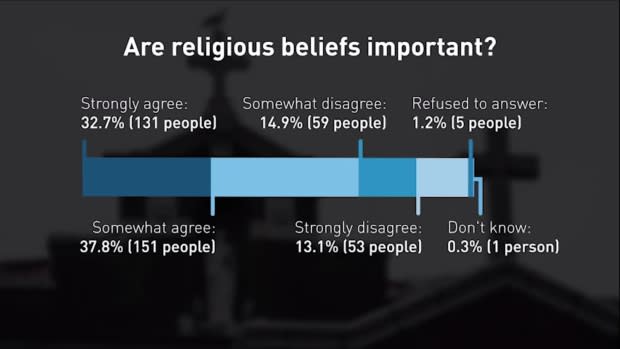

In a new poll conducted by CBC Saskatchewan and the University of Saskatchewan Social Science Research Lab, more than seven in 10 people (70.5 per cent) agreed religious beliefs were important in their lives and more than 28 per cent people said they weren't. Four hundred people responded to the survey, which has a margin of error of +/- 4.9 per cent.

Richards said he still considers religion to be an important part of his life, despite his lack of belief in an interventionist god or an afterlife. Religion has structure, which he said is more of an influence than the idea of God. Religion and culture are so intertwined it's nearly impossible to separate the two, he said.

Use what you're given

For Jerry Peters, who was in seminary to obtain his master's divinity when he began questioning his beliefs, the subject of an afterlife became more important after he stopped believing. Religion is still important to his family, so it's important to Peters. It's his heritage, even if he no longer believes.

"I think the subject of the afterlife became more important to me because how important it was to my close family and friends," Peters said. "Because any time a funeral happens, that's the only time when my beliefs are of greatest concern."

Peters said he would like to live as long as he could, provided there was a good quality of life to be had. While some people might want immortality or to live as long as possible, he accepts that death will happen.

"There's always a time and place for everything — and a time to end it," Peters said.

"So, [being] afraid of not wanting it to end, that's definitely there — but when it happens, it's done. It will only be hard on those who have lost me.

"To me, it's more personal to reflect on the past when someone dies than to try to reflect on some ambiguous afterlife."

A church is a community

Religion, like any institution, can provide people with a social community they can thrive in when it's done in a healthy way, according to Cameron Harder, a retired professor of systematic theology.

Religious institutions, especially in smaller communities such as the ones spread across Sask., provide several functions, Harder said. They're places to talk, to hash out significant questions about what's going on in the community, to gather around and eat.

"They provide really important rituals for community rhythms, you know, the births, the deaths, the marriages and the disasters," he said.

He said a congregation could also help out with general life, such as legal matters and the Canadian bureaucracy, because the clergy are often very educated and have the resources to help if needed.

There are also the same problems that come with being a community. Alienation can occur when people feel churches are overstepping their boundaries.

"I do think that in some ways, the organized church has become, in many places, quite brittle and and it has carried on world views that belong to, let's say the 15th century or something like that, rather than you know staying sort of current," said Harder.

Harder had worked with what he referred to as "non-traditional" ministries and faith groups that engaged with people who had been previously uninvolved with religion in the past.

He spoke about potential parishoners looking for a non-judgmental place of worship — a place where leaders and members of the congregation aren't moral critics, and accept other congregants regardless of who they are or what they have done in life.

"They were looking for a place where difficult questions could be discussed openly without fear of sort of violating Orthodox doctrinal restrictions, or something like that. In other words, they didn't want to be told what to believe," Harder said.

"They wanted to explore this great mystery with a group of curious open-minded people."