After Living in the U.S. For 31 Years, I’ll Be Voting for the First Time on November 3

I remember it like it was yesterday. I was walking out of JFK Airport after a 26-hour-long flight, and was hit by air so cold it shocked my skin and soul. It was early March, and I only had a light jacket to protect me from the winter weather. (What else would a 9-year-old who’s only lived in the tropics have on hand?) I realized then, as I entered my uncle’s car in New York City, that my life would never be the same.

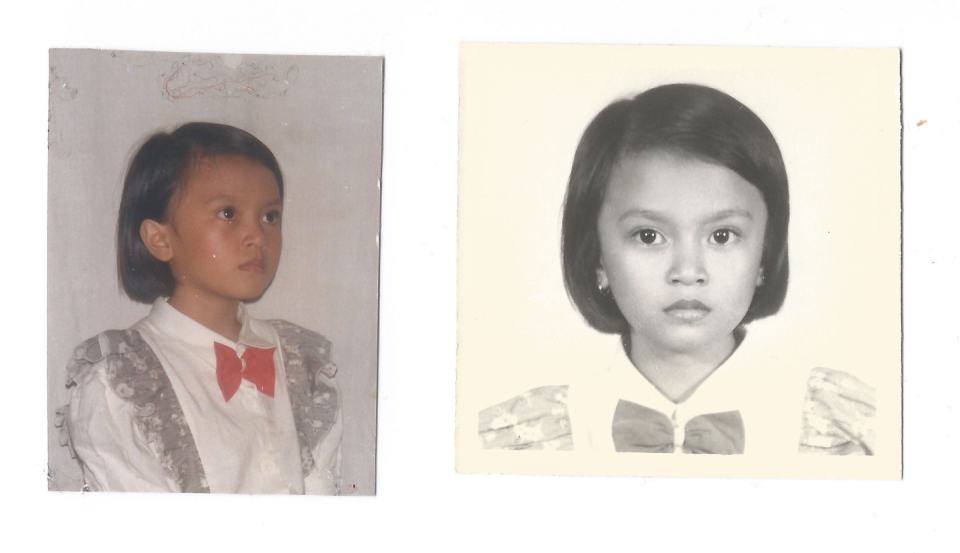

For the next three decades, I’d eat, sleep, learn, and live as an American, which was quite different from the last decade I spent in Manila, Philippines. My breakfast of rice with sweet sausage was replaced by sugary cereals. Instead of watching (and rewatching) Neverending Story on Betamax (not even VHS), I could choose from hundreds of shows on hundreds of channels to entertain me. But most importantly, my family and I would have more opportunity. Just a few years prior, at 6 years old, I went with my parents to a non-violent, political demonstration that “surprised the world,” as news outlets put it. It was called the People Power Revolution, where citizens resisted the regime violence and electoral fraud of then President Ferdinand Marcos.

Life was about to be very different, but my allegiance would be in limbo.

Every few years, I would find myself at an immigration building in Newark, NJ, renewing my green card, something that was gifted to me after my uncle petitioned for us to come and take permanent residence in the United States. That green card meant that I can virtually live here forever. I wasn’t just a visitor.

When I came of age and got my first job, I paid taxes and contributed to my social security just like everyone else. I reaped the same in-state benefits when I attended a state school for college as other New Jersey residents. I was afforded the same advantages as my friends who were born here — except when it came to voting.

Permanent residents can’t vote. So, I didn’t.

One by one, my friends and I turned 18, but none of us really talked about voting. Sure, some of them probably exercised the right, but it wasn’t a thing we — or anyone around us — discussed at length. Maybe it was because we were not “full-fledged” adults yet. Maybe it’s because we didn’t have Facebook, and the shareability factor of an election was limited. Maybe it’s because politics at the time was just … different. My fellow Gen-X’ers may have had issues that meant a lot to them and supported all of the Rock the Vote campaigns celebrities got behind, but as a whole, the win or loss of a candidate (even if it was their candidate) didn’t hold as much weight. If your person didn’t get elected, you didn’t feel doomed — not like today.

So I skipped the polls during my 20s and 30s. It wasn’t something I was proud of, but it also wasn’t at the top of my to-do-list either. My parents eventually became citizens so they could vote. I had turned 18 by that point, so I wasn’t “grandfathered” into their citizenship process as is with most children. My sister took it upon herself to apply for citizenship and became naturalized in the early 2000s. Meanwhile, I was busy focusing on earning my degree in journalism, and had no time, energy, or money to spare.

The one time my lack of citizenship bothered me was when a member of my husband’s family asked me if I could get a green card after we had gotten married, as if I was using my spouse to stay in the country like some 90-day fiance. This was in 2013, and the first time I truly felt “othered.” But still, that didn’t send me to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website to download a form to make me feel more “official.”

Fast forward to 2016 and my opinion of citizenship changed overnight.

Leading up to the presidential election between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, the division in our nation became obvious. Random Facebook “friends,” my uncle who’d brought my family and I here for the “American dream,” and a couple of my husband’s relatives — people who I once believed were warm towards me — sparred with me on social media once they realized who I was supporting and why. They had negative views of the media and attacked it — and sometimes me — in their Facebook posts and comments. I wanted to scream through my replies that the formal training of a journalist includes courses on journalism ethics, investigative reporting, even communication law. It’s where I learned firsthand how important maintaining your integrity is, and how you only report the facts, never opinion or assumption, when covering the news. Looking back, it was hypocritical of me to be involved in these tense conversations because I couldn’t even vote at the time.

I won’t dive into my stance on the issues and that election, but know this: Hillary Clinton’s loss lit a fire under me to finally become an American citizen after three decades of being just an American resident and a lover-and-taker of the benefits it has given me.

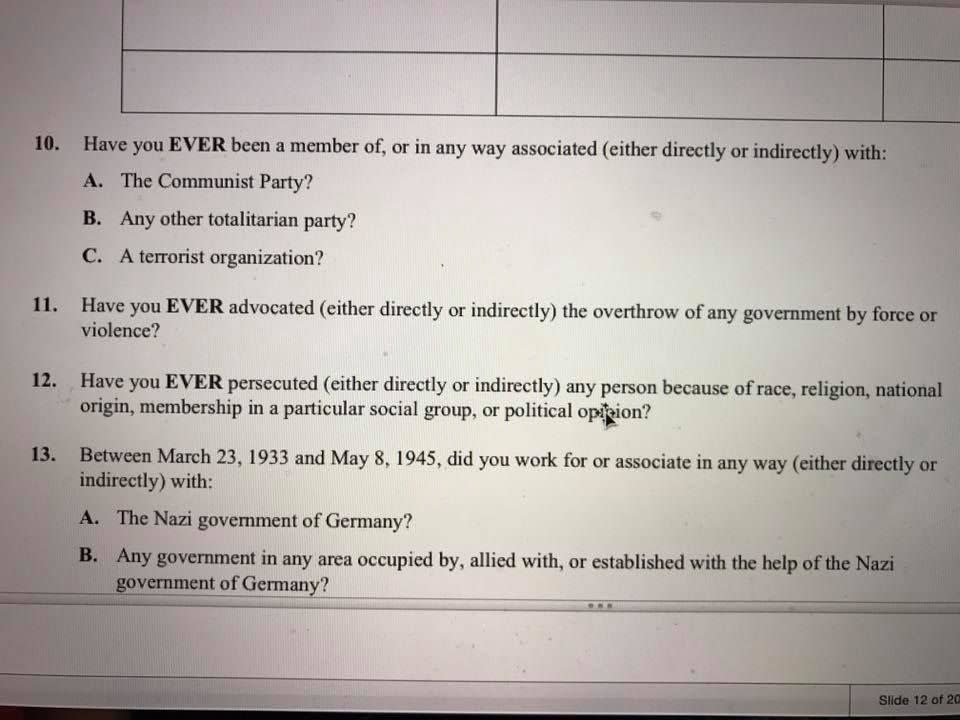

On November 17, 2016 — nine days after the election — I filled out the 20 pages of the N-400 paperwork, paid the $725 application fee, and began the process of naturalization.

I was among 986,851 people who applied for American citizenship in 2017 — up compared to 2015 (which saw 783,062 applicants) and 2016 (which saw 972,151), according to Migration Policy Institute (MPI). MPI notes that the increase has been credited to President Donald Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric during his campaign, coupled with his immigration policies that would soon follow. The process to become a citizen, as well as a backlog of applicants, increased alongside. According to MPI, on average, it takes 15 months to become a citizen. From start to finish, it took me seven months.

Another motivation was the fear that I’d be sent back to my homeland, and separated from my husband and daughter one day should the immigration rules change. I wasn’t illegal or undocumented by any means, but who’s to say that would stand the test of time?

A week before my exam, I downloaded an app to cram for the test. I knew I’d ace it if I just memorized some facts that may have exitted my brain since learning them in middle school history class. Only this time, I was a mom, and “mommy brain” made me forget simple things, like how many congress people each state has and how long they serve.

When it came time, I got every question right. I passed both the written and verbal parts of the test with flying colors. I know this is not always the path for those who walk through the doors of immigration offices, especially those who arrived recently and haven’t received the same education and American experience as me. I consider myself very lucky, especially since about 83,176 people were denied citizenship in 2017, according to MPI. Rejection reasons include: failure to prove the required length of permanent residence (roughly five years), lack of allegiance to the United States, bad moral character, and a failing score on the American civics test.

Shortly after taking the American civics test on June 22, 2017, I was asked to wait in a room full of other successful test takers. Moments later, we were provided with packets that held our naturalization certificates; the cue that we will soon be sworn in. I took a look around the room and saw some immigrants wearing suits and pretty dresses, arm in arm with supportive family members (people who had gotten the memo, unlike me). I sat there alone, wearing a black romper and holding Leah Remini’s book on Scientology of all things. But don’t let my attire that day fool you into thinking this was just an ordinary day for me. I consider it one of the most impactful moments of my life.

Immediately after the swearing in, the agent presiding said to all of us newly naturalized citizens, "Now go. Register. And come 2020, vote. Be heard." There was a collective “yes” that filled the room, like a warm hug from a long lost friend. We know what she meant. Tears soon followed; mine included.

On that day, I took an oath, like everyone else who’s been naturalized before me: “I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same... and that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God."

Those important words strung together in one short paragraph are not lost on me. I understand fully what this obligation and privilege means.

So here I go. By November 3, I will be one of the estimated 156 million eligible voters casting a ballot in the 2020 presidential election. For the first time since setting foot on American soil 30 years ago, I will make a choice that I sincerely believe is for the good of this country that I’ve grown to adore, like a mom loves a child unconditionally — with both the good and the bad.

Subscribe to Woman's Day today and get 73% off your first 12 issues. And while you’re at it, sign up for our FREE newsletter for even more of the Woman's Day content you want.

You Might Also Like