Long story: Exploring the hidden history of Long Island

Long Island, with its steep cliffs topped with red spruce and white birches, is the centrepiece of the picture-perfect riverfront views along the Kennebecasis River.

The island is a popular spot for boaters in the summer, and ATVers, snowmobilers and cross-country skiers in the winter.

The combination of isolation and accessibility are what appeal to Ted Harley, an avid outdoorsman who grew up on the river and spends time on the island every winter.

"It's almost like you're 200 miles from civilization, but you're only five minutes from home," says Harley.

"You don't have an island like this in most places of this world, where you can just go a short distance, summer or winter, and feel like you're in the deep forest."

Many might not know the role it played in the early story of New Brunswick — or that it was once a thriving community with its own school, post office, and riverboat service.

"It has a long history," says Walter Emrich with the Nature Trust of New Brunswick, which protects part of the island. "It's a magnificent island."

Glooscap, graveyards

As it turns out, there are a lot of "Long Islands" in New Brunswick, including in Lake Utopia, off the coast of Grand Manan, and in the St. John River.

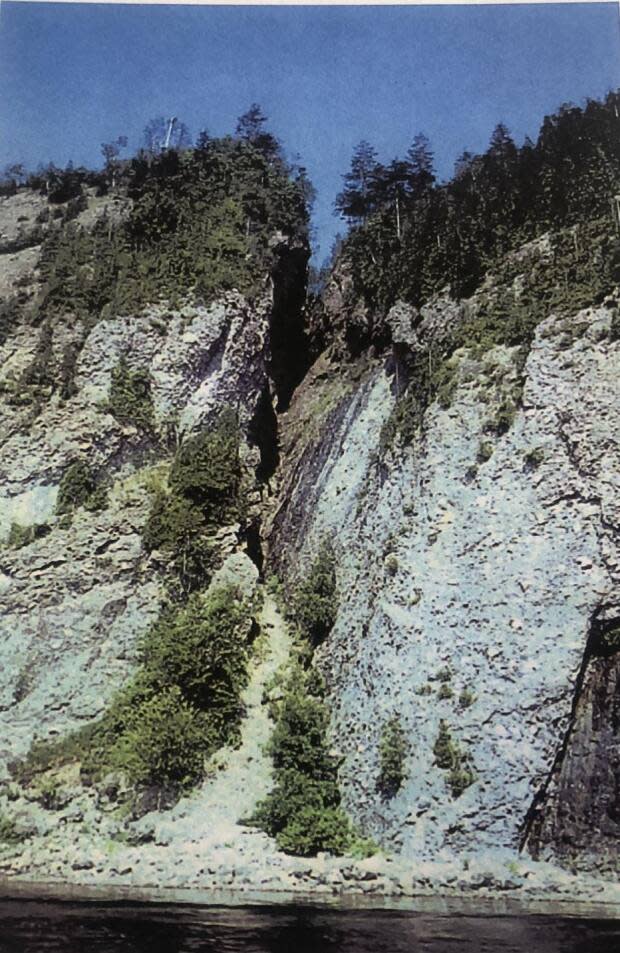

Long Island in the Kennebecasis River is linked with a Wolastoqey legend that the "rock in the river" was home to Glooscap, a godlike giant who split the rock face in two, creating a deep ravine that still has the nickname Glooscap's Gully.

If the Loyalist settlers who arrived there in 1785 expected something similar to Long Island in New York state, they were probably dismayed to find an isolated location, with rocky soil ill-suited to farming. Of the 37 original grantees, only one stayed.

Others soon arrived — from an eclectic mix of backgrounds, as Colin Rayworth, a landowner on the island, writes in his report "The development of Long Island on the Kennebecasis River."

Early Black settlers on the island included Jupiter Watts, who came with his family in 1814 and stayed until at least 1861. Children of the Watts family, and of other settlers, are buried in two small graveyards on the island.

Thriving farming community

By the 1890s, there were 75 families farming buckwheat, oats, potatoes, turnips and other crops.

Settlers eked out a living timbering, and cutting river ice, which was then shipped to Boston in the days before refrigeration.

A school was set up in the 1840s, and post office on the easterly end of the island that was still operating in the 1930s.

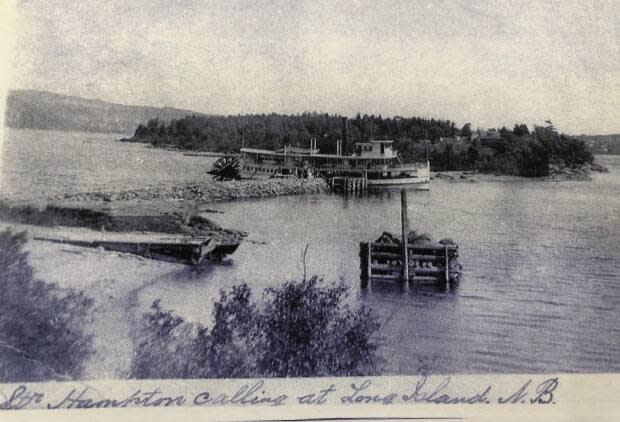

In the late 1800s, a government wharf was built between Long Island and adjoining Mathers Island. The channel between the two islands was dredged, allowing riverboats to pass through.

They made regular stops there until 1921, when the riverboat Hampton made her last run.

In the winter, recalls longtime resident Jennie Breen Willians in her 1972 memoir History of Long Island, residents made a "road" by cutting fir or spruce trees and fitting them in holes in the ice.

"There, they froze, so many yards apart in a perfect straight line to Rothesay. Now you couldn't get lost at night or in a storm, as you just followed from one tree to another."

It particularly isolated In autumn, when ice started to form, and the few weeks in the spring when the ice began to break up, making boat travel impossible.

The rest of the year, settlers rowed, snow-shoed, or used skates, sleighs and horses, travelling from the mainland on their own steam and ingenuity.

Danger on the ice

That's what people like Ted Harley, and countless others, still do today.

"I've been here thousands of times," Harley says. "My history goes back over 60 years. I learned in a hurry that I had to respect the river at a very young age.

But just because it's close doesn't mean it's safe.

"If you don't respect the river, it'll get ya," says Harley. "There can be big waves, and big storms out there. It's a big body of water, a mile wide and over 100 feet deep. It's probably close to a kilometre to get over. Lots of people still do it."

Travelling over the ice, as many people have done in the winter of 2020-2021, is particularly risky.

With numerous accidents reported on or near the island over the years, flotation jackets, ice picks and safety gear are recommended.

"You have to be prepared if you're going to come over here. We don't want to see anybody hurt," Harley says.

"You can't count on anybody else. By the time people react and come out to help you, chances are that they won't be able to."

The last year-round resident moved off in the 1960s.

While the stone foundations and traces of the old settlements are still visible, in 2021 only seasonal cottages remain.

A piece of history

Several areas of Long Island are protected by the Nature Trust of New Brunswick. It's a stop for at-risk peregrine falcons, and home to the extremely rare wall-rue fern, not previously found anywhere in New Brunswick

The Nature Trust, and local volunteers, maintain a network of trails along the old Long Island Road.

"We are trying to clean up the trail system," says Shaylyn Wallace, the stewardship co-ordinator with the Nature Trust. "We're thinking about extending the trail, if there's interest in it."

"We've had people doing surveys for birds and lichen as species change over the years, and invasive species removal."

Many people, including Ted Harley, hope that "the future is the status quo."

"There are certain groups of people that for some reason think they can just throw their stuff on the ground and someone else will pick it up."

That's a shame, he says, considering "it's a piece of history. There's no doubt about it.

"We are so lucky to have it here, and accessible, where private landowners haven't bought it all and made it unusable for the general public."

"We want to make sure that anyone else who comes over here is not abusing it — to keep it clean and pristine."