Looking for signs of life in B.C's rare glass sponge reefs

The first scientific exploration of two rare glass sponge reefs off British Columbia's coast has revealed one healthy reef and one mostly dead, ancient reef.

A team of federal researchers and members of B.C.'s Kitsumkalum First Nation have been studying the recently discovered and extremely rare glass sponge reefs in Chatham Sound, near Prince Rupert, for the last week.

"What we saw this morning was definitely a geologically sound reef with a low live sponge cover. It still seemed to provide homes to quite a few animals but we don't know whether and how this reef will rebuild its live sponge cover," said Anya Dunham, the chief government scientist on the trip.

Glass sponge reefs are only found in B.C. and Alaska and are so fragile that even sediment stirred up by fishing gear or nearby development can damage or kill them.

Leading up to the expedition, scientists were optimistic they might be looking at the oldest and healthiest intact glass sponge reefs in the world.

Indeed, in the western part of the sound, near Dundas Island, the team noted evidence of a very large and likely very old living sponge reef.

But the central part of Chatham Sound revealed just fragments of the extremely fragile sponges.

Essential to local ecoystem

"It seems like too much sediment is not good," Dunham said. "They need a certain amount of flow of sediment to feed and grow," Dunham said.

They are also sensitive to changes in temperature, exist only within a narrow range of ocean salinity levels and require the presence of dissolved silica in the water to grow, according to Dunham.

Nevertheless, she believes the reefs are an essential part of the local ecosystem.

"What we saw today was probably just a small fraction of the number of different fish and invertebrates that they support."

'Like condos of glass'

While individual glass sponges appear around the globe, glass sponge reefs were thought to have disappeared 40 million years ago — until the discovery of a massive reef in Hecate Strait in 1987.

Scientists believe the sponges act as both a giant ocean filter and essential habitat for marine life.

Dunham said even a small reef will filter "tremendous amounts of water" and support a large number of fish and invertebrates.

The towers, which can grow as high as an eight-storey building, are "almost like condos of glass for the different species that find refuge there," she said.

It's unclear how much of an impact it would have if those glass condos were to disappear or sustain significant damage.

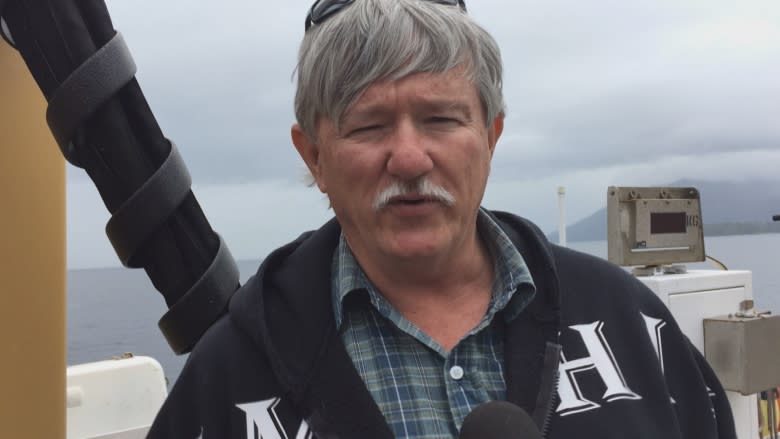

That's why Mark Biagi, the manager of fish and wildlife operations for the Kitsumkalum First Nation in nearby Terrace, wants to see them protected.

"Are they important? Absolutely they're important," said Biagi.

"That's our food and [we've depended] on that food since time immemorial and we need to protect those sites because if we don't protect the habitat we will lose the resource."

Kitsumkalum is located about 140 kilometres inland from Prince Rupert on the Skeena River, which has been a source of salmon, eulachon and other ocean-dependant food fisheries for nearby First Nations for thousands of years.

In the winters, Biagi said the tribes would travel toward the coast where weather was fairer and food was plentiful.

Discovered during LNG exploration

The reefs Biagi is looking to protect were discovered by Spectra Energy during an environmental assessment for an underwater LNG pipeline route in 2012, but that discovery wasn't made public until 2016.

Biagi said the fact it was found during the environmental assessment is significant, because it shows that the process works.

"It's not perfect, but because of that, we found them. Now we have to figure out how we protect them," he said.

Dunham said reefs are put at risk by a number of factors, but damage is guaranteed if the reefs are contacted by fishing gear or structural development.

"By protecting [the reefs] I'm not saying that we're opposed to every [development proposal] — it's just that we need to understand the ecological significance of things and adapt the projects so that we can do both, have both, without the total destruction of the ecosystem we depend on."

'Little islands' of hope

The Kitsumkalum fisheries office has purchased its own remote underwater vehicle to continue gathering data to share with other First Nations and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Biagi hopes having access to the ROV to explore the sea floor will inspire his team to dedicate their lives to protecting the fisheries.

"My goal is that they get so interested in protecting the environment that they're going to continue their education and go into university, come up with masters and PhDs and take over the position of running the show for Kitsumkalum into the future," he said.

While the team was disappointed the Chatham reef wasn't found in perfect health, Dunham said she still has hope for its future.

"Sometimes it's more exciting to see the little islands of live ones among the mostly dead areas because you see that as potential for recovery," she said.

To hear the full interviews with Dunham and Biagi click the audio titled 'Looking for signs of life in northwest B.C.'s rare glass sponge reef'

For more stories from northern B.C. follow CBC Daybreak North on Facebook.