Métis trapper witness to 60 years of Fort McMurray history

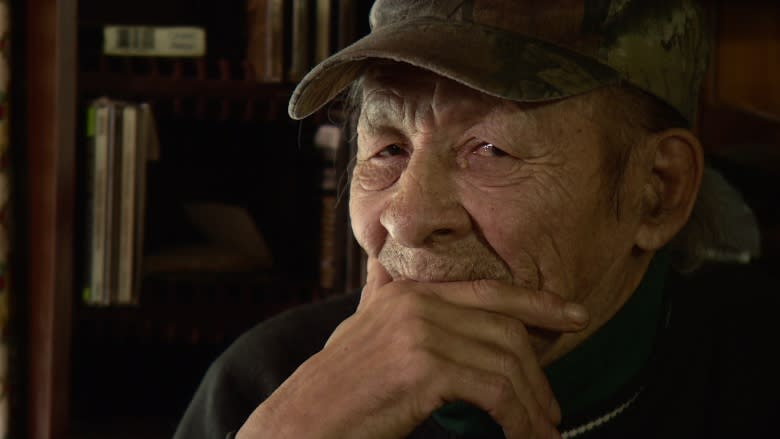

His dark, mischievous eyes first opened on Canada Day, and it is fitting, somehow, that he shares a birthday with the only country on Earth where his life story would be possible.

It is, almost, as if some mythic, 19th-century national DNA flows in his veins — his bloodline part Cree, part French, part European adventurer.

Through 74 winters and summers now, Alcide Joseph Floyde Boucher has made his home, and his living, in the immense boreal forest that covers much of northern Alberta.

It is a place where a few rugged individuals can still live off the land, much as their ancestors did for centuries.

But it is also a place where the quest for riches that lie underneath that land — billions of barrels of oil trapped in sand — has utterly transformed vast tracts of the landscape into something akin to a moonscape.

In the course of one man's lifetime, Fort McMurray has grown from a sleepy little town in the valley of the Athabasca River into a boom-and-bust oil city where fortunes have been made and lost, again and again.

Though his Métis card lists all four names, he uses only one. Massey.

Life along the No. 2277

The nickname came from an uncle, who was known as Mac after the truck company. That uncle decided to pass on the tradition, naming his nephew after the tractor manufacturer Massey-Ferguson.

So, Massey it is.

On the wall of his small cabin, 50 kilometres south of the city, there is a battery-powered clock with a knife and fork for hands.

He knows that the clock, that time itself, runs only in one direction.

"You can't rewind," he said, looking out the window at huge snowflakes swirling down on a recent winter morning. "I wish it was back then, now."

He has lived his own version of back then, in this particular cabin surrounded by a forest of spruce trees, for the past decade.

But he has been a trapper for much longer than that.

This winter, for the first time in years, he did not work his trapline. The line, No. 2277, belonged to his auntie Eva Huppie who died last year at age 85. Somehow, as the family grieved, the paperwork to apply for the annual licence renewal was forgotten.

A new generation of coureur de bois

Massey was born in Lac La Biche, almost 300 kilometres south of Fort McMurray, on July 1, 1941. Cree was his first language, then French, then English. As a boy, he attended a Catholic mission school — 29 children in one room with a single teacher whose name he still recalls.

He can trace his family back with certainty to his grandfather, Charlie Voosterum, who came to Canada from Sweden and settled in the Lac La Biche area. He knows Charlie married an aboriginal woman named Betsey Quintal, and that they had eight children.

Census data collected by the Métis National Council shows a Betsey Quintall was born in Lac La Biche in 1886, the daughter of Etienne Quintal, who was born there in 1850.

Based on those records, it seems clear that Massey's family has been in the area for more than 150 years, and likely much longer.

A plaque he received from the Métis association notes, in passing, that his great-grandfather was a coureur de bois, a French-Canadian woodsman.

The Athabasca River basin around Fort McMurray was originally inhabited by Métis and aboriginal people — chiefly Cree, Chipewyan and Dene, according to a historical overview of the area published in 2000 by the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board.

Those original inhabitants were the first people to make practical use of the oilsands. In 1788, the explorer Alexander MacKenzie noted the local people used bitumen mixed with spruce tree gum to waterproof their canoes.

In the first decades of the 20th century, two separate communities co-existed in the Athabasca River valley. One was named after William McMurray, a chief factor with the Hudson's Bay Company. To the south was the hamlet of Waterways, where most of the residents were Métis. The flatlands in between were known as The Prairie.

'The road was just gravel'

When Massey first arrived in 1959, about 1,100 people lived in Fort McMurray.

"Everybody knew each other," he said. "The road was just gravel. Cabs from Waterways to McMurray, 50 cents.

"They had wooden sidewalks. In some places you walked on tarsands. It didn't smell good but you were used to it."

No one he knew at the time had any idea that this tar-like substance would one day change everything and be worth billions of dollars, or that people from all over the country, and beyond, would relocate to northern Alberta to seek their fortunes in an industry now widely referred to as the economic engine of Canada.

Massey never dreamed of making it rich. His first job in the area was with McGinnis Fisheries, where he earned 90 cents an hour, working four men to a boat, hauling nets of whitefish, pickerel and jackfish out of Lake Athabasca. For a time, he worked for the Northern Alberta Railroad, cleaning switches and replacing rotted ties.

By then, things were already changing.

'The water looks just like copper'

After decades of test wells and experiments with hot-water extraction, in 1962 a company called Great Canadian Oil Sands Ltd. was granted permission to produce 31,500 barrels per day.

Construction of the plant north of Fort McMurray was completed in 1967.

That was the beginning of all the changes. The population was about 2,700 then.

Within five years, the city was home to 6,800 people. The population is now more than 60,000, and Fort McMurray has spread up into the hills above the old town.

Though Massey's cabin is miles from the city, and miles from the nearest oilsands plant, he sees changes all around him.

He used to take water straight from the creeks, or melt buckets of snow in the winter. Now he needs help from the people at Métis Local 1935 to fetch water from town.

"In winter, sometimes, you see the snow turned yellow on top," he said. "Or even in summer, the water looks just like copper on top.

"Before, you could use the snow for water. Now you can't use it. The Athabasca River was good. Now you can't use the river. You can't eat the fish."

He thinks the strange colour comes from sulphur that spews from smoke stakes on the huge oilsands plants.

"Sometimes in summer," he said, "the leaves on the willows turn brown. It must be from the (oilsands) plants."

'Clearcuts all over'

There are several pipelines near his cabin. In summer, the companies cut down trees and brush along the right-aways. They plow down a lot of blueberry bushes, he said.

"They spray the pipelines," he said, to keep down the weeds. "And the moose will go there and eat the leaves. Meat's no good. That's how it goes."

He thinks the noise from the highways, from construction, from all the people, has scared away many of the animals.

"Clearcuts all over," he said. "Where are the animals going to go, eh? They just leave.

"I used to see here a lot of moose, deer. But now, the double-lane highway, you barely see anything.

"Lot of things have changed. Last summer, not one bear came around here."

There used to be more trappers in the area, too, but many have given it up.

"Trapping is just like gambling," he said. "Some days you don't get nothing, eh?"

When he does trap, he goes after lynx, fisher, otter, marten, fox, coyote, mink, even the odd wolverine.

The seasons for most animals run through the winter, when their fur is heaviest.

When he catches animals, he lugs the frozen carcasses into the cabin and lays them on the floor beside the iron stove.

"You've got to thaw them slowly," he said. "Otherwise, the skin on their bellies turns green."

The animals have to be skinned, and scraped clean with tools he makes from deer leg bones. Then the fur is stretched, and finally bundled and stored.

'Nobody bothers you'

In spring, he takes his furs into town and ships them to North American Fur Auctions, the largest company of its kind.

"I made $2,400 here once, that was the most I made," he recalled.

His snug cabin is decorated with family photos and dozens of ball caps people have given him over the years.

He runs power off a pair of 12-volt car batteries just inside the door. He uses them to listen to the radio or charge his cellphone. When the batteries run down, he recharges them with a gasoline generator.

The wood stove keeps the cabin warm. At night, he lights kerosene lamps.

His nearest neighbour is another trapper, about 25 kilometres away.

"We don't bother each other," he said.

The solitude, being alone with his dog, Buck, suits Massey.

"I like it better than town. Peaceful. Nobody bothers you."

Peaceful, except for the constant din of traffic on Highway 63, the main road that connects Fort McMurray to Edmonton and the world beyond. The mostly-twinned highway, busy with trucks and heavy haulers carrying massive pieces of equipment, passes about 150 yards from his cabin.

"Before I couldn't stand it," he said. "Now I'm used to it."