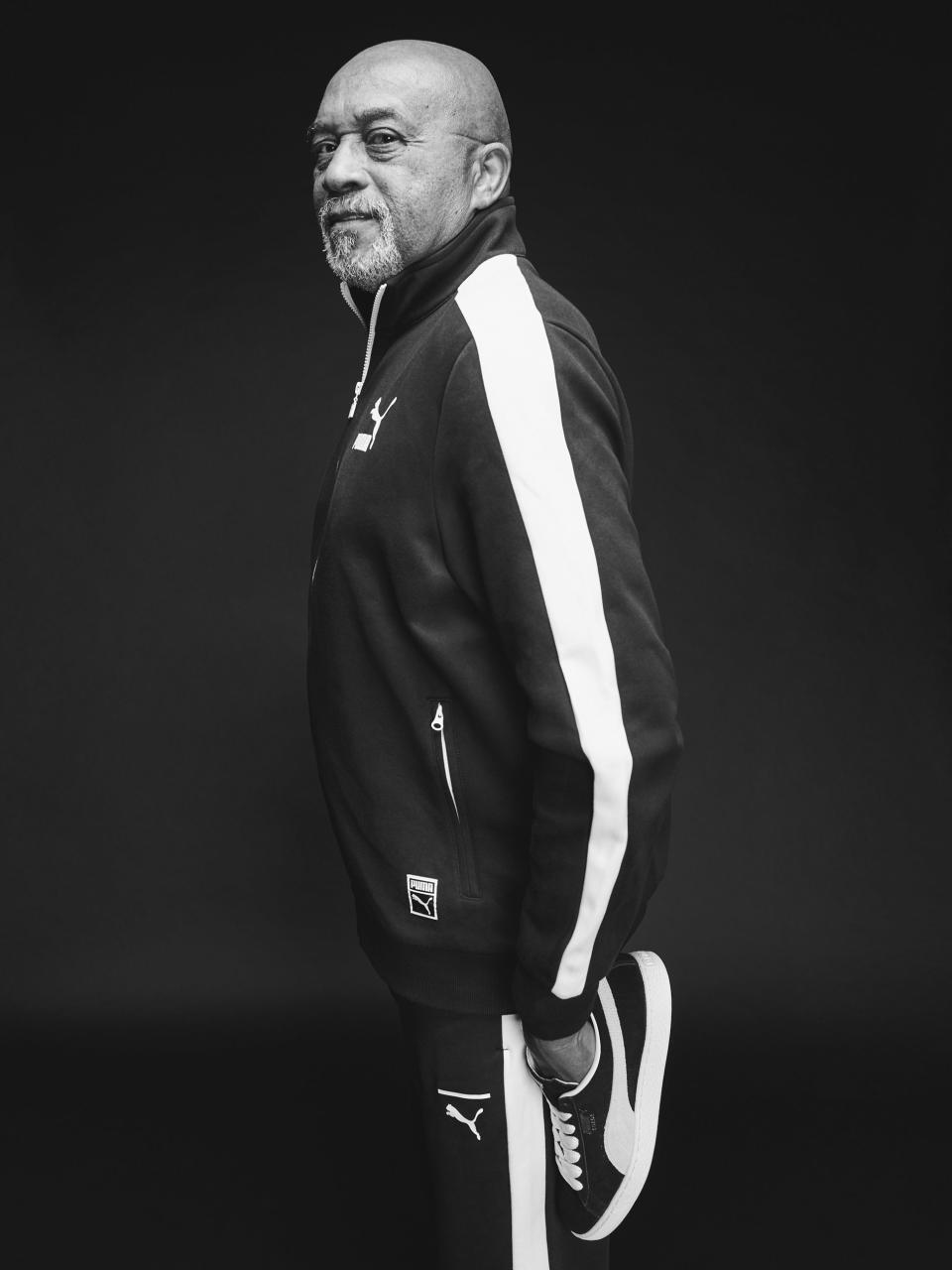

The Man Behind the Fist: Olympic Icon Tommie Smith’s Enduring Protest

Tommie Smith crouched into starting position. One knee on the cinder track, the other so close to his face he could kiss it. His long, lean arms held him in place; only the tips of his fingers touched the ground. His chin fell to his chest, as if in prayer. At the gun, he exploded out of the blocks and his mind went blank. Exactly 20 seconds later, he flew across the finish line of a straight 200-meter dash at San Jose State University, where he was a sophomore in college. It would be the first of Smith’s 13 world records. He was 20 years old.

It was March 1965, a time of urgent activism—that same week, some 2,300 miles to the east, Martin Luther King Jr. and scores of others were walking from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery—and Smith was eager to take part. Immediately after the race, he folded his 6’4” frame into a friend’s Volkswagen Beetle and they raced out of town to meet 200 fellow protesters at a midpoint along their 45-mile march from San Jose State University to the Federal Building in San Francisco—a demonstration against racial inequality in American schools.

“That was the first march that I remember being a part of,” Smith said one recent afternoon, recalling the determination he felt. “I certainly wanted to run that day, and I certainly wanted to be in that march. No matter what, I had to be in front—marching in front and winning that race.” Smith was celebrated as one of the fastest men in the world, but off the track, he felt like a “second-class citizen” because he was Black. “When I was running, I was part of this fraternity,” he said. “But when I stepped off the track, I was less than.”

Three years after that march, King would be assassinated in Memphis. Six months after that, Smith would win a gold medal for the U.S. in the 200 meters at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. You know the famous photograph: Smith on the podium with his teammate John Carlos, the bronze medalist, their heads bowed, each with a black-gloved fist high in the air; in the other, a Black suede Puma shoe. On their feet they wear only black socks. The silver medalist, a white Australian sprinter named Peter Norman, stands in front, his arms straight against his sides. On his green tracksuit, in a gesture of solidarity that would shape the rest of his life, he wears the same button as Carlos and Smith—a white circle with green laurel branches framing simple, black text: Olympic Project for Human Rights, a campaign co-founded by Smith and Carlos in 1967 to protest racist policies of the International Olympic Committee.

Widely misinterpreted as a militant Black Power call to arms, Smith and Carlos’s clenched fists represented solidarity and strength; their shoeless feet, the poverty of far too many Black Americans. Carlos wore a string of beads around his neck to signify the lynchings that continued to plague the American South. Smith made a point to flex a small muscle in his wrist, one he calls a “class muscle” because he developed it picking cotton. Norman, who did not help plan the protest, borrowed the OPHR button moments before the ceremony to show his support. In 1968, their demonstration was deemed, at best, an inappropriate marriage of politics and sport. At worst, it was seen as a threat by two angry, young Black men and a white sympathizer to violently overthrow the status quo. It effectively ended all three of their running careers.

Now, more than half a century later, Smith’s story finds renewed salience in a documentary released this month, The Stand: How One Gesture Shook the World. Directed by Becky Paige and Tom Ratcliffe, the film examines both the enduring power of that gesture and the pain endured by the men behind it. Its August release comes six weeks after NFL commissioner Roger Goodell urged a team to sign former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick and voiced support for his activism—four years too late, many would say. For Smith and Carlos, such an apology is no longer an option: Their version of Goodell—Avery Brundage, the International Olympic Committee chairman who sent them home from Mexico City—is long dead, and their careers have run their course. What we can do now is watch their story and marvel at how fast they were—Smith’s 19.83 in the 200 meters in 1968 would have won him a silver medal at the 2016 Olympics, five-hundredths of a second behind Usain Bolt—and at how relevant their legacy remains in the fight against injustice.

When Smith, now 76, thinks back to that moment on the podium, he thinks of his father, a laborer and a devout man, and of the values that were instilled in him from a young age. “I wanted to make a life like my father would want,” he said. “To be a man, a Christian man, that treated everybody like he would want to be treated. I didn’t see how athletics had very much to do with this, until I learned the importance of me running, of me competing.”

I reached Smith by phone at his home in Stone Mountain, Georgia, a small city northeast of Atlanta where the largest Confederate monument in the United States continues to assert its dominion over the region’s rolling green hills. Carved into an enormous rock face that rises from the earth like a tsunami, the Confederate trinity of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson gaze out from their 40-story granite perch. It was the site of the 1915 rally that incited the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, and, nearly half a century later, a reference in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. “Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia,” King proclaimed from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial—a connection Smith made only after moving to Stone Mountain, in 2005. It gives him enormous pride. “When I walk through that park, I don’t think about that engraving,” he said. “I think about Dr. Martin Luther King, what he said, and I look at the people who are walking around, and I see more people of color than white folks.”

Smith was born in 1944, in Clarksville, Texas, a small town just a few miles from the Oklahoma state line. He was the seventh of 12 kids. All the white children in Clarksville went to school in town; Smith and other Black children went to a school in the woods. Whenever a white family approached Tommie or any of his siblings as they were walking down a sidewalk, they knew to step into the street and let the white family pass. No one questioned it, and no one ever used the word racism. “Daddy didn’t teach the differences,” Smith said of his father, James Richard Smith Sr., a dark-skinned field worker with a third-grade education and a short bloodline to Madagascar. “He taught us what he knew, which was manual labor.”

As a child, Smith watched his father and his uncles play baseball in the pastures around Clarksville. “Sports were what kept us safe in the backwoods of Texas, away from the animals,” he said. He would later channel the work ethic his father imparted into his athletics, and eventually, into activism. “Everyone loves a winner, and even I love winning, but I didn’t see how winning could be a part of social change,” he said. “Now, I do. But then, I did not know.”

In 1951, 7-year-old Tommie boarded a labor bus with his family and moved to California. Forty miles south of Fresno, outside a town called Stratford, Smith worked the cotton and grape fields and dug irrigation ditches; sometimes he slept in them to keep warm. And it was there that he developed his first inkling of how racism manifests in American life. “It was when I moved to California that I became educated to the difference between Black and white,” he said. “I’m going to a white school, with white children, and they’re getting taught one thing on the test, and getting good grades, and learning words, and I’m wondering, like, what that word ‘objective’ means.” To Smith, they might as well have been raised in two different countries. “We didn’t know what the white folks knew.”

By high school, Smith knew he wanted a college education. In 1963 he started at San Jose State, where he won a scholarship to play basketball his freshman year. Sophomore year he ran track. Then football. He was a natural at every sport he tried. The next few years brought world records, an NFL draft selection by the Los Angeles Rams, the Olympics, and finally, a bachelor’s degree in sociology. “I went to college to understand,” Smith said. “I wasn’t taught to go to school to rally for human rights. Where I come from there’s no such thing as whites and Blacks working together on the same platform of equality.”

Smith and Carlos’s famous gesture of protest was, in fact, a Plan B. The previous year, they had co-founded the Olympic Project for Human Rights along with a young sociology professor at San Jose State named Harry Edwards. Their initial plan was to boycott the games unless the International Olympic Committee met four conditions: hire more Black assistant coaches, restore Muhammad Ali’s title as the world heavyweight boxing champion, replace Avery Brudage, the longstanding and openly segregationist president of the IOC, and disinvite South Africa and Rhodesia, both African states under white-minority rule that intended to send all-white teams to the games. Not all of the conditions were met, but Smith and Carlos decided to compete anyway. If they medaled, they’d use the opportunity to get their message out another way.

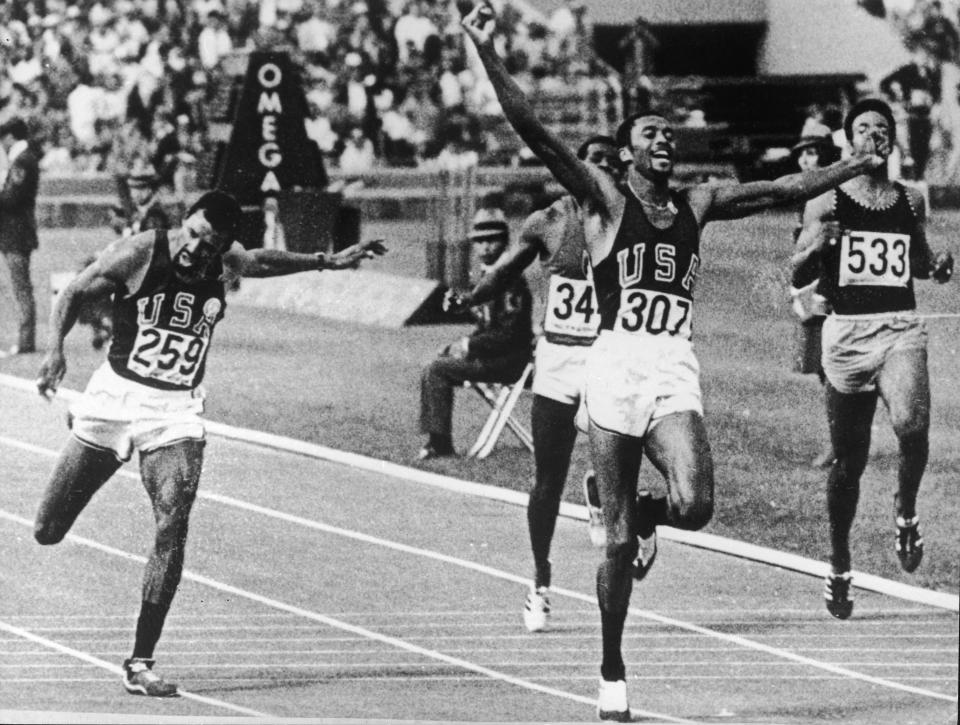

For Smith, that was a big if. He finished first in the semifinals earlier in the day but pulled a groin muscle so badly that he was convinced he’d been shot. Only the lack of blood assured him he was mistaken. When he got into position for the finals a short while later, he thought he had only so many strides in him before the muscle gave out. At the gun, Smith once again exploded out of the blocks and tucked into the middle of the pack, taking the turn at 18 miles per hour. On the straight, he started reeling his rivals in. Ten meters from the finish, he was so secure in his lead that he slowed his cadence and threw his arms in the air. He crossed in 19.83, a new world record and the first time the 20-second barrier was broken using an electronic timing system.

As Smith, Carlos, and Norman made their way off the field after the awards ceremony, spectators jeered at them. The next day, the two Americans were ejected from the Olympic Village and given 48 hours to leave the country. Norman returned to his native Australia a pariah. Although he met the qualifying standards a full 13 times to compete in the 1972 games, he was not sent to Munich. The International Olympic Committee attempted to strip Smith and Carlos of their medals. Both men received death threats.

After the 1968 games, Smith, Carlos, and Norman remained friends, though they didn’t maintain regular contact. Carlos struggled throughout the 1970s. He worked odd jobs, suffered a divorce, played football in Canada, and eventually became a high school track coach in Palm Springs. Norman returned to his former career, playing Australian football, and began coaching in 1978. An Achilles tendon rupture in 1985 led to gangrene, followed by depression, alcoholism, and an addiction to prescription painkillers. When he died, in 2006 at age 64, Smith and Carlos were pallbearers at his funeral.

In the 2008 documentary Salute, Norman explains his decision to wear the OPHR button as a matter of course: “I believe in human rights,” he said in an interview shortly before he passed away. “I remember how durable he was,” Smith told me, recalling a party after the Olympics where Norman told him about his family’s work with the Salvation Army. “He was going to go home and try to spread the good news of human rights. He was a very hard worker.”

After winning gold, Smith went to visit his own family in Stratford, California. He found his father in the fields, feeding hogs. People had been telling him that his son had done something that “wasn’t right” at the Olympics, and he wanted Tommie to explain. As Smith recounted their conversation to me, he sounded by turns wistful and amused.

“I said, ‘Well, daddy, you raised us to treat everybody right, and go to church, and that’s good. I like that, daddy.’”

His father wiped the sweat from his brow, kept working, and asked again: “Well, what happened?”

“I told him nothing happened. I told him that he taught me to keep my head high, and talk like I’m respectful, and be truthful in my belief. And that’s where we started to understand each other.”

His father stopped what he was doing and stood up to face his son. “So, you was telling the truth to these people?”

“I said, ‘Yes sir, that’s about it.’”

“Oh, well that ain’t bad,” he father said, and went back to feeding the hogs.

Mens 200m At The Mexico City Olympics

After college, Smith was drafted by the Cincinnati Bengals and earned a master’s degree from Goddard College. In 1972 he took a job as the assistant director of athletics at Oberlin College, the first coeducational college in the U.S. and the first white institution to admit black students. Smith was hired by the school’s new athletic director, Jack Scott, a self-described “populist radical” who also hired Cass Jackson, the first Black head football coach to serve a predominantly white college.

In 1973, Howard Cosell of ABC Sports visited Oberlin to report on the changes Scott was bringing to the college, then controversial enough to warrant a segment on national television. Sitting in the bleachers alongside the track, Cosell asked Smith, then 28, if he thought he’d changed since 1968, if he’d grown less militant. “What does militant mean?” Smith asked, cracking a wry smile. Cosell raised his voice in a mock-scold: “Don’t spar with me, we’re not going back to ’68 Tommie! Militant means a guy who speaks out in protest, whether by physical symbol or vocally with a truculence attached to his tone of voice, against the existing establishment and its procedures. Now, with that premise, have you changed?” Smith smiled, straightened his shoulders, and replied: “I am a militant.”

At Oberlin, Smith learned to see “all sides” of the debate over equal rights, he said. “I had to see the Black side and the white side. I had to understand the unconscious bias of racist ideology.” Ultimately, he decided that the only way to effect change was to focus on what unites us. “Some people have Chevrolets, some people have Fords, but they use them to go to the same places,” he said. “I think that human nature is basically the same.” In 1978, Smith took a job as head track coach and professor of physical education at Santa Monica College, where he remained for 27 years. “It will not be easy to replace a legend,” the local paper, The Santa Monica Mirror, wrote of his retirement in 2005.

It’s hard to imagine Smith retiring as a legend if he’d stayed in Texas, where he’d always been taught to do as he was told and not make trouble, where he wasn’t allowed to eat in certain restaurants, or go to school with white children. But he believes he’d have been the same man. “It didn’t make a difference to me where I was, so long as I maintained my beliefs,” he told me. “I might not be alive, but I would have died with the same beliefs.”

Forty years after the Mexico City games, when Usain Bolt set three world records at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, Smith presented him with one of the shoes he wore that night in 1968. Explaining why he chose to give the shoe to a Jamaican sprinter rather than an American, Smith told me, “Usain Bolt is a Puma athlete, and I view myself as a Puma athlete.” Although Smith set all of his other world records in Adidas, the company never gave him a dime. “Not one, they didn’t even call me,” he said. “I only ran one race in Puma shoes, the 1968 Olympic Games.” But if he was ever in need—$50 here, $100 there—the company was there for him. “I have always given allegiance to those that help those in need.”

Smith seldom attends protests today, but he celebrates those who continue to speak out and march for justice in the age of Black Lives Matter. “The superficial feeling of freedom has been broken wide open,” he said of the current movement. He wants for “everyone to understand—maybe not agree with—but understand the need for change,” he said. “Maybe then we can stop all this blood in the streets.”

In 2005, Smith moved with his wife, Delois, to Stone Mountain, more than 50 years after he boarded that labor bus from Texas to California. He hadn’t lived in the South since. But it’s affordable, he told me, and their daughter had been looking at colleges. Many of the best Historically Black Colleges and Universities are in the Atlanta area. They looked at 42 houses, and chose the 42nd. Fifty years ago, their town was whites-only; a leader of the KKK once lived just two miles from where the Smiths live now. Today, the area is mixed; the Smiths’ neighbors on either side are Black. They live on an acre and a half of land in a tidy neocolonial with a big porch and tall columns. Smith cleared the trees on his front lawn so he can see the road, where cars waving Confederate flags often pass by on their way to the monument. To Smith, it’s still home, though. “I know the racism of the South,” he said. “But I don’t run from racism.”

Originally Appeared on GQ