Man claiming to be ex-premier's son finds no answer in unsealed documents

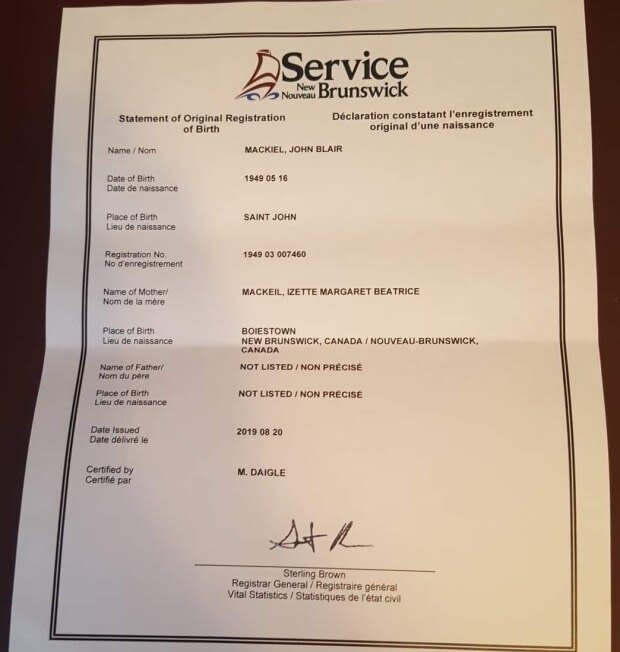

"Name of Father: Not listed."

With those few words, John Hall's final bid to get the New Brunswick government to release the name of his biological father from the province's vault of formerly sealed adoption records came to an inconclusive end earlier this month.

"That's OK," said the 70-year-old semi-retired realtor from his home in Florida, just weeks after paying a visit to some of the Hatfield clan in Hartland.

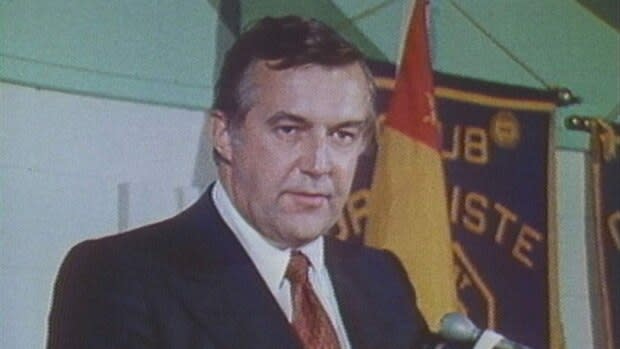

"I'm saying to them, 'As far as I'm concerned I'm Richard Hatfield's son, unless you can prove otherwise.'"

After meeting two of the former premier's nieces and two nephews in person, Hall said he is certain they are also his kin.

"Everyone there said I'm the spitting image of Richard," said Hall.

"They brought out pictures of Richard — ones that I had never seen — and it was mind-boggling."

Since New Brunswick unsealed its adoption records last year, Social Development has received and processed 519 requests for statements of original birth registration.

For some people, this will be the first time they see the registered names of their birth parents — names that had been guarded for decades for fear of disrupting the lives of families affected by adoptions.

When Hall's statement arrived in his Brooksville, Fla., mailbox in early September, it confirmed half his story.

His mother's name is listed as Izetta McKeil, but Hall already knew that everyone called her Toodie.

Locals in the Hartland area had solved that part of the puzzle, using clues from the so-called non-identifying information that New Brunswick's post-adoption services had released to Hall in 2001.

That's how he knew he was born at the Evangeline home for unwed mothers in Saint John in 1949 to a "quiet girl" who was 19 and single.

Toodie died in 1991, before Hall could meet her. But he did track down her grown children living in Ontario.

They were the ones who remembered their mother's lifelong interest in Hatfield and how she wrote about him in her self-authored obituary.

They also shared a vivid recollection of a summer trip to New Brunswick in 1965 that ended with a stop at the Hatfield potato chip factory, where they waited with their father in the hot and sticky family car, chomping on potato chips so Toodie could say "goodbye to Dickie."

Father's name still guarded

The 2001 non-identifying letter also told Hall that his birth father was named in his file, but the legislation of the day prevented the department from disclosing it.

Marie Crouse said that hasn't changed, even today.

Names of fathers whispered by mothers who felt scared or ashamed, names jotted down in social workers' notes or as part of a doctor's briefs are not revealed unless the father signed off on paternity.

"Parents sent these girls away for secrecy and lots of times the fathers didn't even know anything about it." said Crouse, who was just a 15-year-old Hartland High School student when she got pregnant in the early 1960s.

Her parents handled the situation the same way thousands of New Brunswick families managed unplanned pregnancies in the decades after the Second World War.

Crouse was banished to Saint John to the Evangeline maternity hospital under the care of The Salvation Army.

As soon as that baby was formerly adopted, Crouse was denied access to the names of her daughter's adoptive parents and the new name they gave her -- making it impossible to track her down.

"Some people had the mistaken idea that by opening the records, that the government would just pass along all the papers, the whole thing. Well, that was never the case," said Crouse.

Speaking from 30 years of experience with ParentFinders NB, a volunteer group that helps adult adoptees find out where they came from, Crouse thinks it's very likely that 99 per cent of the new documents processed since April 2018 will not list the names of fathers.

Hall said he never did expect to see a name. For him, the blank is no surprise.

Not all stories end well

Garth McCrea, of Woodstock, is another adoptee who did not get the answers or the happy reunions he longed for.

Born at the Evangeline home 54 years ago, he applied for his unsealed records and got them back with his father's name not listed.

His birth mother's name was listed but he decided to leave her alone.

He'd been told by post-adoption services that they had contacted her in 2007 and again, at McCrea's pleading, after he suffered a stroke in 2016.

Both times, he was told by government workers that she declined to be identified to her son and did not want to hear from him.

"She said she did not want to be exposed because her marriage would fall apart and her life would fall apart," said McCrea.

"She has made a decision for her brothers, her sisters, her kids, everybody in her life, she has made this decision and I have to stand by and accept it."

"I don't need to embarrass a lady that I've never met before."