Manhattan jail where Jeffrey Epstein died has long history of suicide, neglect

NEW YORK — Jeffrey Epstein lived in a lavish Upper East Side mansion, but he met his end in a hulking building in lower Manhattan. A few blocks away from the jail where he died over the weekend is the federal courthouse where Epstein, who once socialized with both Presidents Donald Trump and Bill Clinton, would have faced justice for running what prosecutors have called a vast sex trafficking ring that exploited underage girls.

The accounting never happened: Epstein was found dead in his cell on Saturday morning at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, or MCC, the federal detention center where he was being held. His likely suicide has left many wondering how a high-profile detainee could have evaded observation long enough to successfully commit the act, especially since he had tried to kill himself only three weeks earlier.

The answer lies with the MCC, where the federal government has held some of the most notorious criminal figures of the past several decades, from organized crime boss John Gotti to drug lord Joaquín Guzmán, better known as El Chapo. Those held there are detainees, not prisoners, as they are still awaiting trial. As such, they are afforded the same presumption of innocence that all defendants in the American criminal justice system enjoy.

While Epstein’s suicide has understandably been front-page news for the past several days, troubling conditions have plagued the MCC as long as the building has stood in lower Manhattan. Intended as an example of improvements in the nation’s carceral system, it instead became an example of that system at its very worst.

“When I would come home from sessions from the MCC, I would tell my wife, ‘I need to do something life-affirming tonight,’” says a former federal prosecutor whose law firm requested he speak only on condition of anonymity when discussing his prior employment. He described his visits to the detention center as “soul-depleting” because of the conditions he witnessed there.

“It was a dark, dank, low-ceilinged prison with obvious rat and roach infestations,” the former federal prosecutor said, comparing the MCC unfavorably to Attica, the notorious New York state prison.

The MCC opened in 1975. The 12-floor building cost $15 million and boasted “central air-conditioning, closed-circuit television, carpeted corridors and no bars at the especially strengthened clear plastic windows.” At the dedication of the building, Deputy U.S. Attorney General Harold Tyler expressed hope that the new facility would have “a great and salutary impact.”

That has not come to pass. A combination of institutional corruption, tolerated cruelty, persistent overcrowding and an eternal lack of proper funding has contributed, over the years, to the jail becoming a “a rat-infested, high-rise hell,” as the news site Gothamist called the MCC in a 2018 report. As for those windows, they look today like nothing more than dull slats of grime.

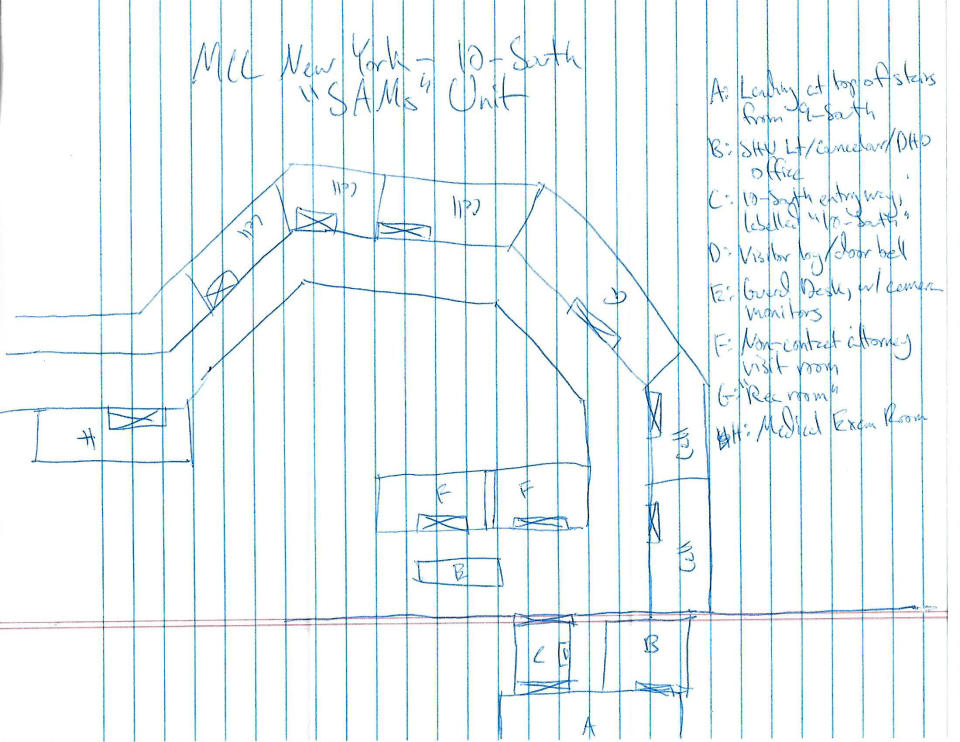

Ron Kuby, the prominent civil rights lawyer, has represented “many, many” people held at the MCC. He explains that because the facility holds so many dangerous suspected criminals, the officials there are guided by a single principle: “Nobody can escape from there.” Kuby struggled to think of a single successful escape from the MCC (though a hijacked helicopter came close to helping a detainee escape in 1981).

“Everything else is secondary to security,” Kuby said, whether it’s medical care or access to legal representation. “The rest is just ... whatever.”

Just four months after the MCC opened, detainees filed suit, contending that their rights were being violated. They compiled a litany of complaints, including overcrowded cells, intrusive searches and a lack of reading material. That legal battle, known as Bell v. Wolfish, ended up before the U.S. Supreme Court four years later. A 5-4 majority led by Justice William Rehnquist, a Nixon-appointed conservative, decided that the conditions did not infringe on detainees’ civil rights.

Justice Thurgood Marshall, a longstanding champion of civil rights, disagreed. In a dissenting opinion that would prove prescient, he wrote that “the rights of detainees apparently extend only so far as detention officials decide that cost and security will permit,” sharply criticizing this “unthinking deference to administrative convenience.”

The day after the decision in Bell v. Wolfish was reached by the high court, Roger Stowe of Queens, a ceramics student who had been arrested on drug charges, “slashed his arms with a double‐edged razor blade in his cell,” according to the New York Times. A guard found him “bleeding profusely,” the paper said.

Stowe was the second suicide at the MCC in the first four years of its opening. The first had taken place in 1977, when a detainee accused of robbing a bank with his wife hanged himself. (Hard-to-come-by newspaper accounts of that suicide, along with others at the MCC, have been unearthed by Daily Beast editor Harry Siegel.)

Corruption has also been a problem from the start. In 1976, four guards were accused of facilitating the smuggling of goods for MCC inmate Carmine Galante, a powerful figure in organized crime. Another inmate, Raymond Wean, described the kinds of contraband that could be found inside the seemingly impregnable facility: “Cigars, booze, cigarettes, or anything we wanted,” as Wean put it, according to Anthony M. DeStefano’s “King of the Godfathers.”

As a sign of how little had changed, last year a guard admitted to taking $45,000 from a Turkish-Iranian businessman, Reza Zarrab, in exchange for contraband such as “alcohol, cellphones, food and vitamin C packets,” according to a Times report.

Most of those confined at the MCC did not have the pull of a Mafia boss or an international financier. Despair came far more easily than Cuban cigars, even for the formerly powerful whose influence did not extend to the fortress on Park Row. Among these was Michele Sidona, an Italian banker who had been accused by American authorities of money laundering. Unwilling to face a jury, he also tried to slash his own wrists. Imprisoned later in Italy, he died of cyanide poisoning in what was believed to be a suicide.

Harsh conditions persisted at the detention center, especially during the tough-on-crime policies of Republican Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. In 1993, according to the New York Times, lawyers complained to a judge about the conditions faced by their defendants. “I am not going to micromanage the MCC,” answered the judge, Michael Mukasey, who would later serve as the U.S. attorney general under George W. Bush.

The week after Mukasey made that pronouncement, there was yet another suicide attempt.

Earlier that year, terrorists had attempted to blow up the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan. The effort failed, but the bomb they set off in the complex’s garage killed six people. The conspirators ended up a few blocks north of the Twin Towers, at the MCC. In November 1993, two of those detainees sought escape via death. They “cut themselves with razors, and one of the two tried to hang himself with a torn bedsheet,” according to the Times. Both were “revived without serious injury.”

Administrations changed in both City Hall and the White House. Criminal justice reforms came and went. But the MCC appeared immune to them all. In 2000, for example, a female former inmate at the MCC alleged in a lawsuit that she had been “repeatedly raped and sexually abused” by an officer of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics while she was detained between 1995 and 1997. Efforts to have MCC administrators take her accusations seriously came to naught, her lawsuit alleged. MCC officials tried to have a summary judgment rendered, but a federal judge refused that motion and the case was eventually settled for $300,000.

In 2014, Roberto Grant was accused of attempting to steal Cartier watches from a Manhattan store. He was sent to the MCC, where he died the following year. Although officials told his mother that he overdosed, there were actually indications that Grant had been severely beaten.

Andrew Laufer, who represented Grant’s mother in a $20 million suit against the Bureau of Prisons, says that “it’s absolutely incredible that something like this could have happened there.” He believes that Grant was “choked to death” and that MCC officials engaged in a “cover-up” regarding the causes of Grant’s death.

“They need to staff properly,” Laufer says. “They need to supervise properly. It’s grossly negligent all over the place.”

MCC officials did not answer a Yahoo News request for comment.

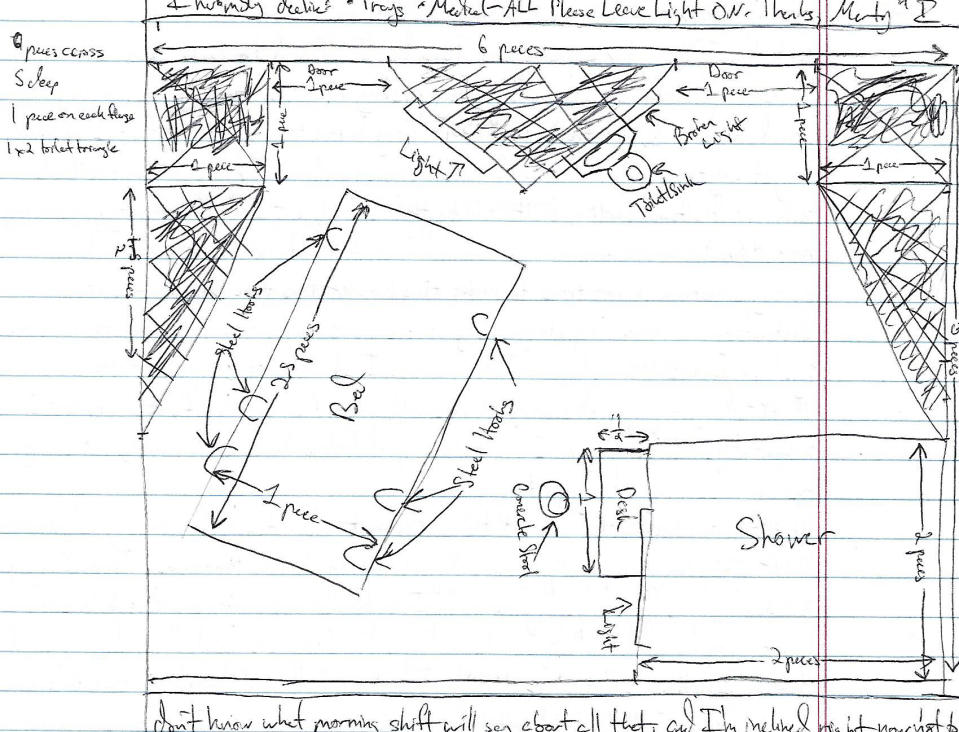

A similar sentiment was echoed in a suit by Levit Fernandini, who’d been arrested in a 2011 drug raid in the Bronx. In his 2015 lawsuit, Fernandini alleged that “the plumbing was not maintained and that the toilets in the facility overflowed, resulting in unbearable filth and smells.”

In addition, Fernandini’s suit described MCC as “overrun with rats and mice and covered in dust and dust mites.” Fernandini claimed he was “bitten by one of the rats, and that the MCC medical staff forced him to wait for treatment and then failed to provide adequate treatment for his bite.”

Dana Gottesfeld’s husband, Martin, spent several months in 2016 and 2017 in the MCC after being transferred from a Rhode Island prison where the activist hacker had been on a hunger strike. “This place is really bad,” Dana said of her husband’s time at the Manhattan facility. She recalls, for example, him saying that inmates would stuff balled-up clothing under the doors to keep out rodents and insects. He is now suing over his treatment there and has been transferred to another facility.

Dana Gottesfeld believes that for all its invocations of security, the MCC suffers from a lack of oversight. “They know they can do what they want and get away with it,” she says of the people who work there. Dana believes that “unannounced surprise visits” by Bureau of Prisons officials could help remedy the situation.

Perhaps the most unusual sign of dysfunction at the MCC took place in 2013, when sentencing for Mansour Arbabsiar, an Iranian would-be assassin of the Saudi ambassador to the United States, had to be postponed because two elevators at the facility simply stopped functioning, and there was no way to transport Arbabsiar from the 10th-floor cell where he was being held.

The elevators were presumably fixed. But the far deeper problems would remain. Much remains unknown about how and why Epstein killed himself. But whatever the ultimate reason, it was a troublingly common fate for federal detainees in lower Manhattan.

The former federal prosecutor who is familiar with operations at the MCC says that anyone who claims to know exactly what happened to Epstein is either “lying or deluded.” He adds that “enough things went against standing protocol to doubt the official story.”

Epstein’s death has infuriated U.S. Attorney General William Barr, who, speaking on Monday, said there had been “serious irregularities” at the MCC. He was right. Only they were there long before Epstein crossed the jail’s threshold.

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: