Manitoba flood forecast data centre getting busy

Senior flood forecaster Fisaha Unduche has plenty to think about, and the information is coming at him from literally millions of sources and numbers.

In addition to hundreds of precipitation stations, "we also monitor satellite data. We also monitor radar data. It all comes into one — we call it meteorological data. Then we have hydrological data — river flows, lake flows, lake levels, river conditions, etc.," Unduche says.

Behind the sandbags and floodways, banks of computers help hold back the rising water that threatens Manitoba in flood season.

Unduche laughs when contrasting the yesteryear image of someone taking readings with a measuring stick and sending the results to Winnipeg by phone to the high-tech operations done today.

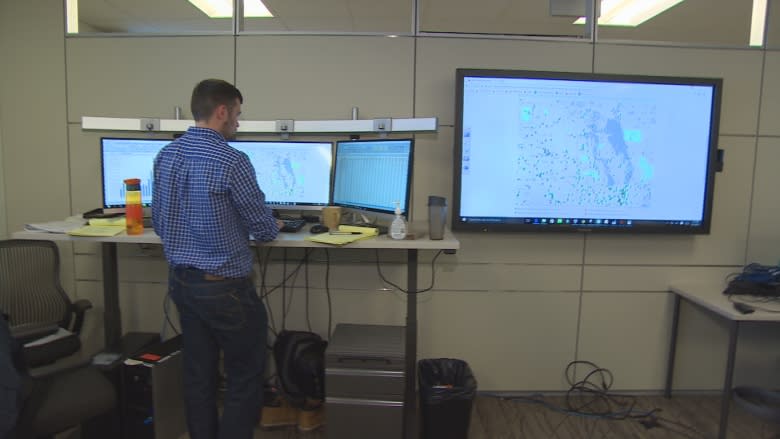

Now supercomputers take in massive amounts of data from sources stretching across four provinces and several American states.

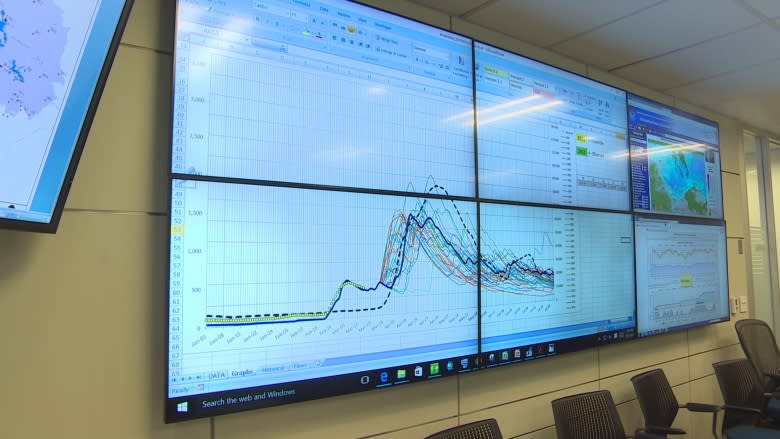

Hydrology forecast engineers crunch big data to generate their flood models, which transmit from banks of screens in front of them onto much larger screens on the walls around the forecast centre.

Manitoba operates more than 100 precipitation stations and takes information from another 600 on this side of the border alone, perhaps 1,000 in total, and that's added to the satellite and radar data, as well as information about river flows, lake levels and other conditions.

Manitoba's flood fighters also draw gigabytes of data from the U.S. National Weather Service.

Our forecasting and modelling systems are similar to those used in the U.S. in a lot of ways, but there are some major differences, Unduche says.

"Their forecast is a national organization. In Canada, it's a provincial jurisdiction, so each province runs a different way," Unduche says.

Another major part of predicting what will flood is looking at what happened in the past; forecasters' models are constantly comparing current data to previous years.

This year, the moisture levels are high, but at least 2017 it isn't looking as bad as the big flood — the "Flood of the Century" — in 1997.

"In 1997, there was significantly more snow than now," Unduche said.

Between November 1996 and April 1997, almost twice as much snow as usual fell on southern Manitoba. The anniversary of a massive snowstorm that precipitated the biggest flood since Winnipeg was flooded in 1950 is coming soon.

The flood forecast centre is really two rooms. The first is where the data miners drill into the big flows of data and create and update their models, and the second is where the decision-makers will meet every morning during the height of flood season — emergency staff, Ministry of Infrastructure officials, political types — and make the tough minute-by-minute decisions.

The team will decide when to open floodways and gates, close roads or deploy crews.

Above-average precipitation in the form of heavy snow in some locations in Manitoba and unusual winter rain in others has bumped up the pace in the flood forecasting centre this spring.

There are some trouble spots.

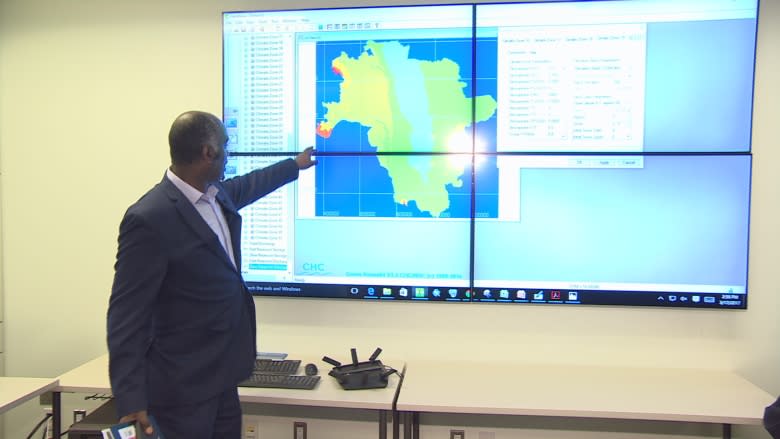

"The southwestern Souris River area, here, and the northern part of the Red River Basin, here, " Unduche says, pointing to places on a map on a large screen in the meeting room.

The Souris River region got more snow in two months than it normally gets in an entire winter.

Crews are doing surveys in the field much earlier than normal and the province has contracted the U.S. National Weather Service to fly earlier-than-normal radar missions to measure the snowpack.

But there is good news: Manitoba is buttoned up tight against flooding, Unduche says.

"Communities are well-protected, so we don't worry about communities. Melita, Souris, Wawanesa are well-protected. On the Red, all the communities are well-protected."

With unfavourable weather, there could be flooding on agricultural land and lowlands, and there is always a chance Highway 75 to the U.S. border could be closed.

Climate change not a big factor, yet

Unduche says climate change is a factor in changing weather patterns, but at a scale much larger than the focus of flood forecasters predicting water levels.

There's "not that much" effect on flood prediction, he says.

"Climate change is a bigger scale. Our models look at 30 years, 60 years. Climate change, we are talking about very big — 100 years, 200 years of data, so I don't think it affects it that much," Unduche says.

And Manitoba is going to flood, regardless of climate change.

"We had a flood in the mid-1980s, we had a flood in the mid-1950s, we have a flood now. So that tells you, naturally, even without climate change, there is going to be a cycle coming that at some point we are going to be dry and some point we are going to flood," Unduche says.

Climate change is a factor in the bigger picture, though, as heavier rains or longer summers creep into the larger patterns of weather.

Man moving water

The artificial movement of water — whether it be for irrigation, drainage or flood mitigation — is controversial, but Unduche doesn't shy away from the topic.

Man moving water is a factor, but it pales in comparison to the impact of the amount of precipitation Manitoba gets in peak years, he says.

"If we look at the Assiniboine [river basin], the precipitation we are getting there in the last many years is significantly above average. Whether there is artificial drainage or not, we are going to get some flooding," he says.

Unduche points to the flood season in 2014, when more than 200 millimetres of rain fell in four days. That event, he says, had nothing to do with artificial flooding.

Land use (which has increased), precipitation, use of dams and waterways are all factors in the prediction of and defence against flooding.

But in Unduche's opinion, drainage is well-regulated in Manitoba.

'No comment' on Saskatchewan's role

Opposition politicians in the Manitoba Legislature have pressed Premier Brian Pallister to intervene with his counterpart, Premier Brad Wall, to halt a new drainage plan in Saskatchewan.

Pallister told the CBC in January that he'd like to partner further with Saskatchewan on water management as part of a long-term plan.

Manitoba farm groups have long accused Saskatchewan of not following proper land-drainage rules, causing spring meltwater to rush downstream into the neighbouring province.

Unduche paused briefly after being asked to weigh in on the controversy, then declined with a polite "no comment."

Best-case scenario

So what kind of weather and water rise does Manitoba want to get to avoid serious floods?

"A gentle melt with less peak coinciding, with no rain on top of snowmelt — that's what we call favourable conditions. So that, that is what we are hoping for," Unduche says.