Northern exposure: Manitoba's northern economy facing serious challenges

It's a long drive, twisting through seemingly endless forest, past lakes, down a long two-lane highway that alternates between patches of broken pavement and gravel.

Eventually Manitoba's Provincial Road 391 comes to an end.

More than a thousand kilometres north of Winnipeg, Lynn Lake is just about as far north as you can drive in Manitoba on an all-weather road.

It's also long been at the end of the road economically.

On the final stretch of 391 — Sherritt Avenue, Lynn Lake's main drag — is the Northern Store, one of the few active businesses in town. A group of residents, including Tommy Caribou, is just sitting around outside.

Caribou's red cap would be familiar to anyone that's been paying even minimal attention to American politics. The slogan, written in white, is slightly modified: "Make Lynn Lake Great Again."

That job has fallen by default to local teacher James Lindsay, Lynn Lake's mayor by acclamation.

"We've been circling the drain here for about 30 years," says Lindsay, walking along Sherritt, past buildings that have been boarded up for years.

"The bottom of that circle is getting smaller and smaller."

In the 1970s and '80s, Lynn Lake was far more than just the end of the road; it was a destination.

Nickel and gold mining made it a true northern boom town.

In its heyday, 3,500 people lived here. The mines provided good-paying local jobs, while the taxes and royalties they generated helped prop up the provincial treasury.

Today, the mines are long gone.

Only about 700 people remain. More than half the homes and businesses sit empty and boarded up.

Along the south side of town, hundreds of thousands of tonnes of discarded rock are spread out over the site of the former nickel mine.

Most of the remaining jobs here are at the local school and the hospital, and some in northern construction. Lynn Lake is a testament to the perils of relying on a single-industry, resource-driven economy.

Lindsay says the town has long fought to hold on.

"We're trying to diversify what it is we have here for economic activity and the kind of people we can attract," he says.

A cautionary tale

Extreme as the story of Lynn Lake is, it's a cautionary tale that's resonating through Manitoba's north, where a rough summer is turning into an uncertain fall.

First it was the loss of 100 full- and part-time jobs in Churchill, where a lack of grain shipments forced the country's only subarctic seaport to stay closed this year. Its future is still uncertain.

Its owner, Omni-Trax, says it no longer wants to run the business and is looking for a buyer.

Just weeks later, bad news spread to The Pas.

The town's largest employer, Tolko is shutting down its heavy paper plant in December, taking away 350 jobs. That's on top of other closures already announced.

Flin Flon expects to lose two mines by 2020.

In Thompson, 750 people will be out of work when Vale closes its nickel smelter in 2018.

No bailouts

As in Lynn Lake, the buzzword in each community is "diversify." Easy to say, hard to achieve when you're hundreds of kilometres off the Trans-Canada Highway and generally out of sight.

Manitoba's new Progressive Conservative government has been clear: it's not bailing anyone out.

"We think there are opportunities there," said Cliff Cullen, Manitoba's minister of growth, enterprise and trade. "We think our role as a government is to make sure Manitoba is a competitive jurisdiction so we can attract investment."

But he offers few specifics, saying the government is working on a plan and looking at other jurisdictions like Quebec, which is attracting mining interest with its Plan Nord.

It's not a lot to bank on if you're holding a pink slip.

A golden future?

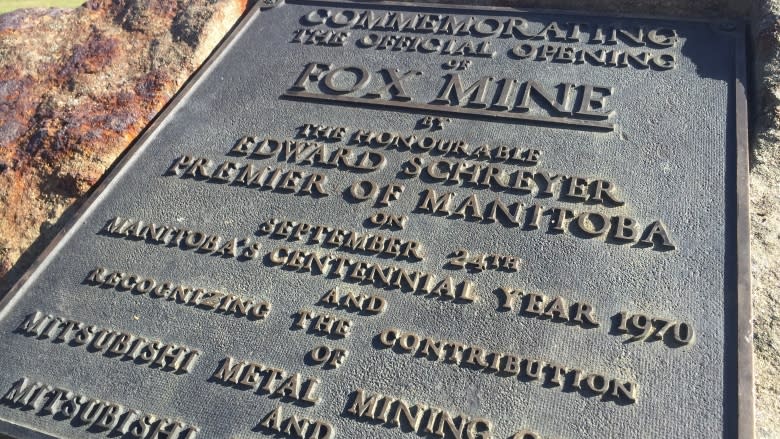

Back in Lynn Lake, there is a plaque outside a small museum dedicated to the area's mining history.

Containing visible streaks of iron pyrite (commonly known as fool's gold), it marks the opening of the Fox gold mine in 1970.

Originally a symbol of hope for the future, today it's more like a memorial to the glory days of the past.

Yet for all the bad news that's hit this region lately, Lynn Lake may have the most promising future.

Alamos Gold has set up an office and is talking about reopening a mining property shut down since the 1990s.

"People are a little more optimistic," says Lindsay.

A mine would certainly bring jobs and opportunity back to the region. People may even move back into those boarded-up houses.

But Lindsay says Lynn Lake can't stake its entire future on one mine. He says revenues from taxes and royalties need to be reinvested in the north, to build infrastructure and capacity, if it's to truly break out of the boom-and-bust cycle of relying on resources.

"It's going to take some creative thinking and awesome leadership," he says.

Two commodities that may be more valuable to northern Manitoba's future than anything else.