Maritime Iron proposes others claw back emissions to offset its high-pollution plant

The company pitching a high-pollution iron plant in northern New Brunswick says the provincial government should get other industries and emitters to cut their emissions to accommodate the new facility.

Maritime Iron acknowledges in its environmental impact assessment document that "implementing the project will make it difficult for New Brunswick to achieve its current aspirational climate change goal" once the plant begins operating in 2022.

But the company boldly proposes that the province simply encourage other emitters to scale back their emissions enough to stay on target.

"Before 2030, New Brunswick would need to identify opportunities to meet this target through reductions across all sectors, including continued efforts and cooperation by the industrial sector as well as reductions in the transportation and electricity sectors," the document says.

The document says the proposed plant, which would process iron ore into pig iron, would create a net increase of 2.3 million tonnes in greenhouse gas emissions.

How the province would find corresponding reductions elsewhere isn't clear.

"Will it need to reach down into the refinery and reduce greenhouse gases there? Will it have to reach down into the forest sector and reduce emissions there?" asked Lois Corbett of the Conservation Council of New Brunswick.

"Where will those other tonnes, millions of tonnes, come from?"

Emission targets in reach

The province's legislated emissions goal for this year is 14.8 million tonnes, and for 2030 it's 10.7 million tonnes. It also has a second, less stringent 2030 goal, 14.1 million tonnes, tied to Canada's Paris climate plan objectives.

New Brunswick's emissions in 2017 were 14.3 million tonnes, below the legislated 2020 target and close to the 2030 Paris target.

To stay close to those targets would require offsetting Maritime Iron's 2.3 million tonnes of emissions reductions.

To put that in perspective, the required offset represents three-quarters of what the Irving Oil refinery emits in greenhouse gases annually, about three million tonnes.

The offset would be nine times what J.D. Irving's four biggest polluting plants put out. Three JDI mills and its Atlantic Wallboard plant emitted 259,000 tonnes of CO2 in 2017.

Maritime Iron did not respond to a request for comment.

Think-tank says industry did its part

While the company is calling for reductions in industrial, transportation and electricity sectors to make room for its increased emissions, the head of a Saint John energy think-tank says industry has already done its part.

"To date, from 2005 to 2020, most of the heavy lifting, the reductions, have been on the backs of oil refining and electricity generation," said Colleen d'Entremont, president of the Atlantica Energy Centre, which is funded by large energy producers and users.

"Now is the time, from 2020 to 2030, for the rest of the sectors to try and make the same gains," she said.

Most of New Brunswick's emissions reductions since 2005 have been attributed to the closures of large forestry mills and power plants.

D'Entremont said there have been "very, very few gains" reducing emissions from transportation, including cars and buses, during the same period. Those emissions were four million tonnes in 2017.

Last year, Irving Oil's director of growth and strategy Andy Carson told a Senate committee there was "a role for us to play" in reducing emissions and fighting climate change. He called it "a very, very significant and important issue" for the province's only oil refiner.

But in December 2019 Reuters news agency reported that the company had quietly dropped its goal of reducing carbon emissions by 17 per cent from 2005 levels by this year.

The company did not respond to a request for comment on Maritime Iron's suggestion about reduced emissions among industrial plants.

JDI vice-president Mary Keith said in an email the company's mills have already exceeded both 2030 reduction targets and the company's forestry operations are a carbon sink, with trees absorbing more carbon dioxide than mills emit.

She said the company would not comment on Maritime Iron's proposal other than to suggest that a federal plan to plant more than two million trees could help offset the iron plant's emissions.

'A really good test case'

D'Entremont said Maritime Iron represents "a really good test case" of whether the province can increase economic activity and create jobs while also hitting emissions targets.

"How are we as a collective going to address the fact that carbon emissions are going to go up?" she said. "What other activities do we have going on that are going to reduce them in other ways?"

She called for the province to fund more technology that would allow "all of us" to reduce emissions and said small nuclear reactors and NB Power's proposed smart meters could play a role.

This week, MLAs on a legislative committee voted to amend the government's carbon-pricing bill for large industry to tie it to the more stringent legislated targets.

The amended bill now says explicitly the pricing system's goal is to regulate emissions "in order to facilitate the achievement" of the targets.

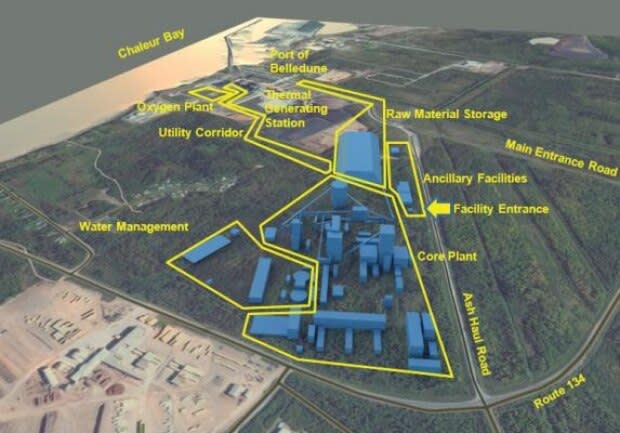

Maritime Iron proposes to link its iron plant to NB Power's generating station so it can sell gas byproduct to the generating station, allowing it to cut its use of coal.

The two facilities combined would emit 4.9 million tonnes of greenhouse gases, or 2.3 million more than what Belledune now emits on its own.

The company argues that Maritime Iron's location will reduce shipping distances for both raw iron ore and finished pig iron, lowering emissions from ocean-going freighters.

That and the company's new processing technology will contribute to global emissions reductions even while increasing emissions in New Brunswick, the company says.

The existing federal climate plan doesn't allow provinces to get credit for emissions created outside their boundaries, and no international credit-trading regime exists.