Microfilm containing historical record of Tsimshian First Nations found at farm in northwest B.C.

The accidental discovery of four reels of microfilm that contain an extensive historical record of the Tsimshian First Nations is creating a buzz in northwestern B.C. Indigenous communities and in the world of academia.

The microfilm turned up last week at Tea Creek Farm in the village of Kitwanga, about 1,230 kilometres northwest of Vancouver. Workers Joel Letendre and Noah Beaton found it in a bin while cleaning out the workshop at the farm owned by Noah's dad, Jacob Beaton.

The information on the reels is a rare collection of the works of Tsimshian hereditary chief and historian William Beynon, who was active from 1912 through the 1950s. In academic circles, Beynon's work in Tsimshian history is considered unparalleled in scope and detail. Much of it is held by the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia and by the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que.

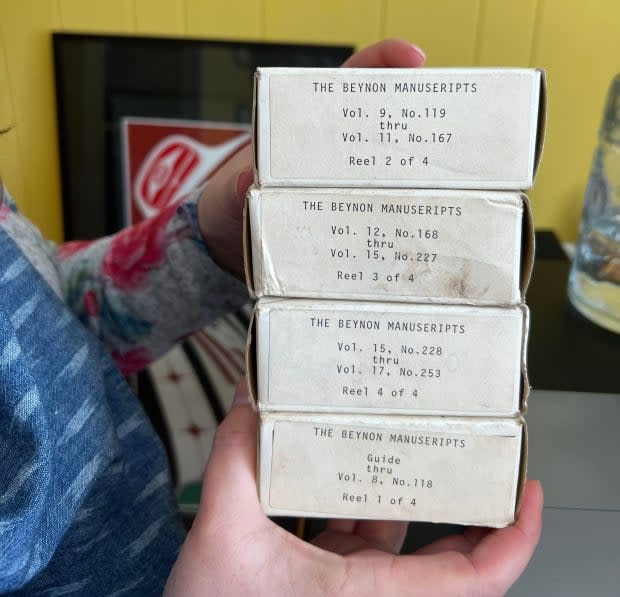

Each of the four boxes found at Tea Creek is labelled with Beynon's name as well as volume numbers.

Jacob Beaton, who is Tsimshian, is still trying to process the significance of the discovery.

"It's phenomenal," he told host Carolina de Ryk on CBC's Daybreak North.

"We've received many, many messages from people, wanting to have a look at them — Indigenous people from here, because he ... documented the Sm'álgyax-speaking cultures, not just Tsimshian but also Nisga'a and Gitxsan."

A 'de facto repatriation'

Chelsey Geralda Armstrong, an assistant professor in Indigenous Studies at Simon Fraser University, says Beynon's field notes and research are some of the most complete accounts of Tsimshian and Gitxsan life in the early 20th century.

Geralda Armstrong was "floored" to find out about the discovery of the Beynon reels at Tea Creek Farm. She says "it could be a really big deal" if some of the information on those reels hasn't previously been published.

From her perspective, even if other copies exist in museums, their value is still immense.

"Jacob finding these, even if they're not all entirely new, it's kind of like this de facto repatriation where now it's in the hands of community members and it's kind of up to them how to store them, how to make them accessible," Geralda Armstrong said. "So there's kind of that sense of it being a gold mine."

Beynon's work gives unfiltered accounts in Sm'álgyax language

According to archived information at the Canadian Museum of History, Beynon was born in Victoria in 1888, the son of a Welsh father and Nisga'a mother. Even though Beynon was educated in Victoria, his mother was insistent that he learn to speak Tsimshian. She also taught him the responsibilities of a hereditary chief, a position he inherited as a young man from his maternal uncle.

In 1915, Beynon was hired as an interpreter by ethnographer Marius Barbeau and worked on and off with Barbeau for more than 40 years, recording and translating myths and songs of the Coast Tsimshian, Southern Tsimshian and Gitxsan peoples.

Geralda Armstrong says one of the qualities that makes Beynon's work so unique, and so valuable as a historical record, is that it hasn't been filtered through a non-Indigenous lens.

"Unlike other anthropologists, when he was interviewing elders and other [Sm'álgyax speakers], he was doing it in Sm'álgyax," she said. "He was talking to them in the language, and then he would even write in his notes — on one side he would have the Sm'álgyax verbatim, and then on the other side he would translate it right away into English, and so it's kind of this unadulterated text."

The Tsimshian First Nations include the Kitselas Band, Kitsumkalum Band, Metlakatla First Nation, Gitga'at First Nation and the Kitasoo Band in the Prince Rupert area of northwest B.C. The Tsimshian estimate their numbers at 45,000 people.

Reels found their way to Tea Creek from the U.S.

The reels discovered in the Tea Creek Farm shop appear to have sat forgotten for the past two years.

They ended up in the Beaton family's possession thanks to Jacob Beaton's mom, Patricia Vickers, who received them as a gift when she was doing research for her doctoral dissertation in interdisciplinary studies in the U.S. in 2006.

Vickers says she was in Oklahoma City when linguistic anthropologist John Dunn gave her the reels. Vickers brought them home and held onto them, she says, in hopes of finding a machine on which she could view them. Ultimately, she sent them to grandsons Noah and Ezra a couple of years ago because of their interest in languages.

Vickers says she didn't realize the value of what was in those four boxes.

Now, she's just glad they've surfaced.

"I'm happy, and what's really important to me is those who are working to keep Tsimshian, Gitxsan and Nisga'a languages alive so that we have access to it," she said.

Goal is to make reels more available to Indigenous people

Jacob Beaton says they've been careful with the reels. He says they opened one box to see what was inside. They pulled a bit of reel out of that box but have left the other three closed to keep the contents protected.

The boxes are currently in a safe, dry place.

Jacob says he has reached out to the Royal B.C. Museum in Victoria to see if he can gather more information about the reels and determine if they've already been digitized.

If there isn't a digital version, he says he'd like to know if it's possible to "somehow participate in seeing them digitized and a little more available, as appropriate."

"I'm really hoping that the microfilms … are able to contribute to the cultural revitalization that's underway here and elsewhere," he said.

"Just that fact that they're so hard to find and that they're so precious — there's so much information that [Beynon] captured. I guess that's the next step for us, is making it more available to Indigenous people here who want to relearn our culture."