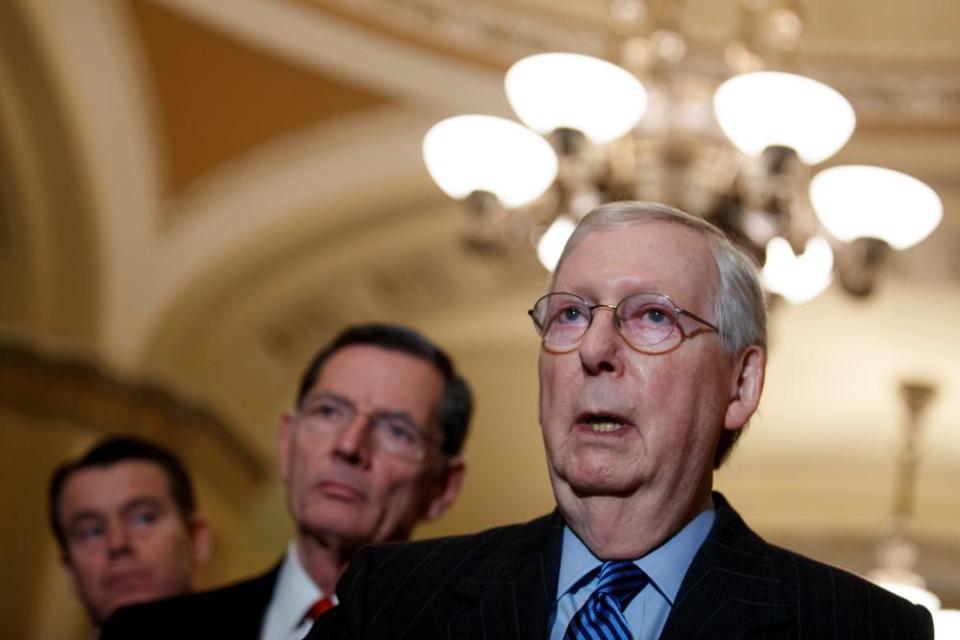

Mitch McConnell: ruthless operator determined to triumph for Trump

For all the hidden pitfalls that a Senate impeachment trial might hold for Donald Trump, he has so far enjoyed the steady support of elected Republicans, and in particular the chamber’s most powerful Republican, Mitch McConnell.

But the majority leader’s backing for Trump represents more than just one more vote in the “acquit” column.

Related: Trump impeachment: Senate prepares to hear opening arguments in trial

As one of the most capable – and ruthless – tacticians in the history of the US Senate, McConnell, the political infighter who became legendary for frustrating the agenda of Barack Obama and monkey-wrenching a supreme court nomination, looks like the ideal figure for Trump to have in charge at this most tenuous moment.

After weeks of vexed attempts by the two parties to settle on ground rules for the Senate impeachment trial, McConnell was expected to muscle through a resolution to open the proceedings early Tuesday afternoon..

It seemed no accident, for those familiar with McConnell’s track record, that the ground rules represented what he has said he wanted all along.

Repeatedly over his 13-year tenure as the Senate Republican leader, McConnell has engaged the opposition in slippery combat – over tax cuts or the debt ceiling or campaign finance reform – and emerged the victor. He blocked dozens of federal judges nominated by Obama and then changed Senate rules to accelerate the confirmation of 185 federal judges nominated by Trump … and counting.

Where no path to outright victory was apparent, McConnell has brandished procedural rules with unprecedented relish, escalating what once were seen as fraternal political arguments into winner-take-all clashes and, critics say, crippling the institution in the process.

Unlike most senators, McConnell has never been known to muse about a future presidential run; instead, his well-known lifelong dream was one day to become Senate majority leader, a dream that came true in early 2015. “He has always been a creature of the Senate,” his wife, Elaine Chao, the labor secretary, has said. “He has incredible respect and understanding of the Senate.”

But the job McConnell faces in Trump’s impeachment trial is unusual. The matter at hand is a trial of sorts, not a piece of legislation. The procedures are different, and sketchier, leaving open the possibility of Republican defections. The national focus is expected to be unusually intense, perhaps increasing the temptation among some Republicans to take a turn in the national spotlight by stepping ever so slightly out of line.

While the US constitution and Senate lay out broad rules for an impeachment trial, rules that govern standards of evidence and the admission of witnesses are left for the Senate to decide, creating a political showdown even before the trial proper gets under way.

The uncertainty also creates room for operators like McConnell to … operate. During the trial, McConnell could have the power to guide the process toward a swift close, or to put an end to Democratic calls for additional witnesses and testimony.

Significantly, Trump and McConnell seem to be closely aligned, with McConnell saying he would coordinate with Trump’s lawyers and Trump praising the legislator’s leadership.

“I’m not an impartial juror,” McConnell said flatly in December. “This is a political process. There is not anything judicial about it. Impeachment is a political decision.”

That kind of pugnacious, sometimes bordering on troll-worthy, speech, is a McConnell trademark. In a widely quoted declaration in 2010, he said: “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

While he shocked Democrats and some Republicans by refusing to take up Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the supreme court in March 2016, months before either party had even nominated a candidate to replace Obama, he made it a point for boasting on the campaign trail.

“One of my proudest moments was when I looked at Barack Obama in the eye and I said, ‘Mr President, you will not fill the supreme court vacancy,’” he told a crowd in Kentucky that year, to enthusiastic cheers. McConnell later casually reversed himself on the underlying debate, saying he would install a Trump-nominated justice in the run-up to 2020, given the opportunity.

Related: Impeachment: Warren accuses Trump of 'wag the dog' strike on Suleimani

For all his political talents, McConnell’s performance as majority leader has been imperfect. He failed to deliver the repeal of Obama’s healthcare law, once the keystone Republican party promise to its base. And he couldn’t prevent Trump from initiating a damaging government shutdown over border wall funding in late 2018. McConnell consistently rates as one of the least popular senators in the country, with a 49% home-state disapproval rating.

But ever since winning his first Senate race in 1984, McConnell has gained more power, and held it more closely. The only child of a chemicals executive and a homemaker growing up in Georgia and Kentucky, McConnell overcame a bout with polio and little natural retail political talent to chart his career.

He began as a moderate, supporting collective bargaining for public employees and even some abortion rights, before hitching his fate to the increasingly conservative right wing of the party. He arrived on Capitol Hill as a Senate aide in 1969 and won his first race, for a county executive seat in Kentucky, in 1976.

In his 2014 book on McConnell, The Cynic, the journalist Alec MacGillis describes how “a guileless young man who was conspicuously uninformed about the mechanics of politics grew into a steely influence broker, proud of his growing sway on Capitol Hill”.

“It is he who symbolizes better than anyone else in politics today,” wrote MacGillis, “the transformation of the Republican party from a broad, nationwide coalition spanning conservatives, moderates, and even some liberals into an ideologically monolithic, demographically constrained unit that political scientists judge without modern historical precedency.”