The modern fairy tale uncovering a true story of brutal Victorian exploitation

The Little Match Girl Strikes Back is a reinterpretation of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale written in 1845 – a highly romanticised depiction of poverty.

In Andersen’s tale, our ‘little match girl’ – a delicate waif with imploring eyes – dies and we all feel sad and perhaps a little cross with all the terrible people who did nothing to help. Our story – or rather Emma Carroll’s story, which I have illustrated – is set about 40 years later in 1888, and based on the real-life strike staged by the girls and women who worked at the Bryant & May factory in east London.

Emma’s match girl, Bridie, needs no narrator to speak for her. She looks us straight in the eye and tells us just what it’s like to walk barefoot through the city streets, selling matches to those who can afford them, in order that her family might eat. She is defiant and courageous – no imploring waif.

It’s a really clever piece of writing on Emma’s part; an engaging way of introducing a child to an incredible moment in history, weaving fairy tale and fact together to create a story that’s pitch perfect for today. I have always enjoyed researching things – particularly a story like this, which was something of a social history lesson for me. I realised I knew almost nothing about the match girls’ strike until I was sent Emma’s story and began reading up on the events surrounding it. The following is a tiny part of what I learned.

The Bryant & May factory employed around 2,000 women at the time of the strike, including children as young as six years old. Payment was poor – close to starvation wages – and the conditions were petty and cruel. The women were allowed only two breaks in their 12- to 14-hour day, and pay would be docked for an unscheduled toilet break, an untidy workstation, dirty feet (though many of the women didn’t own shoes) or cruellest of all, an injury.

The white phosphorus that the matches were dipped into was toxic, and when inhaled it would work its way into the teeth and then the jaw. This affliction, known as ‘phossy jaw’, was excruciatingly painful, disfiguring and potentially fatal. The danger of white phosphorus was widely known at the time, yet factories including Bryant & May chose to continue using it despite there being an alternative: the non-toxic, though more expensive, red phosphorus.

The general working conditions, as well as the appalling wages, for the factory employees were well documented. The catalyst for change, however, only came about when the Fabian Society – a socialist movement founded in 1884 – debated the issue and took a vote to boycott Bryant & May matches.

This led to Fabian Society member Annie Besant publishing a damning article, ‘White Slavery in London’, in The Link magazine in June 1888, which enraged the factory owners, who threatened to sue Besant and sack any employee who refused to sign a paper stating her words were untrue.

One brave worker refused and was sacked, and to Bryant & May’s shock this action galvanised 1,500 of the workers to strike. Despite the risks (and they had everything to lose) they joined together, picketed and negotiated with their employers. They stood by Annie Besant – ‘You had spoken up for us and we weren’t going back on you’ – and she stood by them, along with many others who supported the campaign.

I was commissioned to do nine illustrations – one for each chapter – the challenge being which image best sums up that chapter, engages the reader and propels the story forward. As an illustrator, I focus on what to emphasise, what needs to be explained, how to create emotion and how to draw beyond the words while being faithful to Emma’s vision.

Initially I was asked to do little decorations, but I don’t like doing that, so I chose to work in a few extra drawings – things that I felt were important to highlight. Occasionally, I find something in the text which explains something so perfectly it needs to be illustrated for emphasis. In this case it was a teacup (repeated across the chapters), which was symbolic of Bridie’s dream of a better future.

Her quest to earn enough money to buy a goose for Christmas dinner is also key to the story, since it is Bridie’s resolve to bring a moment of joy to her family. The illustrations are drawn in pencil and then cut up, repositioned and collaged. The patterns and textures in the characters’ clothing come from everyday objects: packaging, dishcloths and the insides of envelopes – it seemed appropriate to use workaday items. The final pieces are black and white with a single colour. We chose red because of the matches, because of the flame, because Bridie’s Irish, and because the factory walls were red.

I worked with book designer David Mackintosh, a longtime friend and colleague, who always brings something special to any project. He’s done some beautiful things with this book – particularly bringing a Victorian sensibility to the type, yet keeping the overall feel contemporary.

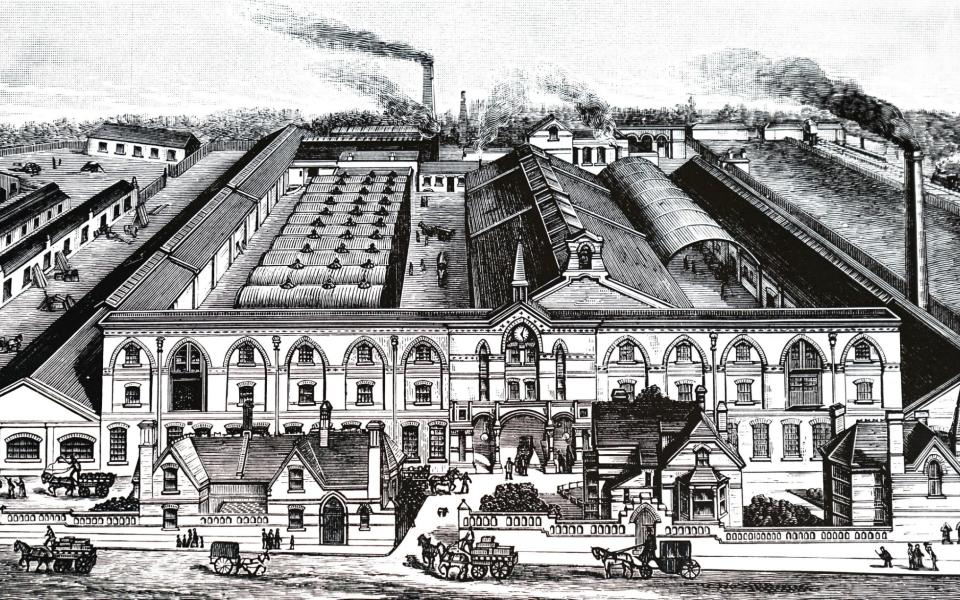

I was incredibly fortunate to have access to so many photographs that accurately depict the conditions these families were enduring in the late 1800s. There are pictures of one-room homes, the streets, the children dressed in ragged clothing, often without footwear. There are pictures of the factory, huge and imposing, of the women at work, neat in their aprons (untidiness could lead to a docking of wages). Most moving are the pictures of the women on strike. They look straight out at the camera. What you cannot miss is how young they are. All these photographs informed my illustrations and I’ve used their faces in my drawings.

It is important to remember these pioneering women of 1888. It is also vital that we understand how relevant this story is to us today, how many families are now living in poverty. But what touched me most, in all my research, are the words from the match girls themselves.

For example, this extract of a letter of support written by them to Annie Besant. ‘We all thank you very much for the kindness you have shown to us. My dear lady, we hope you will not get into any trouble on our behalf, as what you have spoken is quite true… I have no more to say at present, from yours truly, with kind friend’s wishes for you, dear lady, for the kind love you have shown us poor girls.’

It is this standing together that I find so moving, these individuals with very different life experiences, backgrounds, education and means, all working together to bring about change. Their actions still resonate today and I feel immense gratitude for their bravery.

The Little Match Girl Strikes Back is on sale now (£12.99, Simon & Schuster)