Most dikes across southwest B.C. could fail under strain, report warned in 2015

The breach of a dike in Abbotsford, B.C., that contributed to disastrous flooding throughout the Sumas plain was anticipated a 2015 review for the provincial government.

The dike was "too low," "substandard" and "likely needs to be updated" according to a report, written by Northwest Hydraulic Consultants for the Ministry of Forests which looked at 74 dikes across the Lower Mainland.

The report looked at dikes that extend for over 500 kilometres, comprising around half of the total length of those in the province.

The conclusions were grim: 71 per cent of them could be expected to fail during a significant "design event," while none of the dike segments met seismic standards over their entire length.

In addition, half of the province's 178 orphan dikes — that are not under any government's jurisdiction — were in "poor or failing" condition. Upgrading them would cost $865 million, according to a separate 2020 report to the province.

"We've always known the Fraser can generate large floods, but we also need to look ahead, and not increase our exposure and vulnerability over time," said Steve Litke, a senior manager with the Fraser Basin Council, which helps educate organizations and governments about healthy watersheds across southwest B.C.

With multiple atmospheric rivers forecasted for the Lower Mainland this weekend, the stability of those dikes — and why so many are considered in poor condition — is once again under examination.

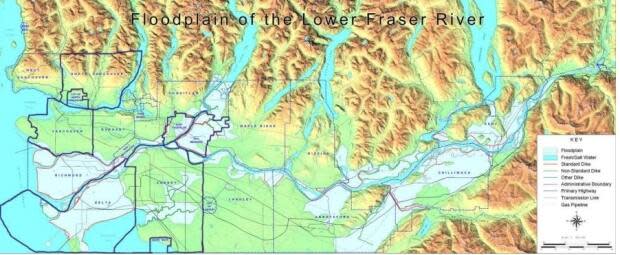

Many municipalities under floodplain

Since the late 19th century, dikes have been installed throughout the Lower Mainland. They are the primary defence from major damage in the region's floodplain, which includes virtually all of Delta, Richmond, Pitt Meadows and Kent, and much of Surrey, Port Coquitlam, Abbotsford and Chilliwack.

Litke says part of the region for the poor ratings is decades of wear and tear, but also to now-higher engineering and environmental standards. He added that plenty of work has been done at the local and regional levels to improve flood mapping and reduce risks.

But that doesn't solve the problem of paying for upgrades — which now falls completely on municipalities, which have limited ways to raise revenue, competing against each other for funding from higher levels of government.

"We could never tax our way out of this. We would bankrupt the city," said Pitt Meadows Mayor Bill Dingwall last year, after a staff report said it could cost approximately $121 million to upgrade the city's dikes.

A city report in 2020 said "nearly all" its dikes will "overtop or fail in the most extreme flood events."

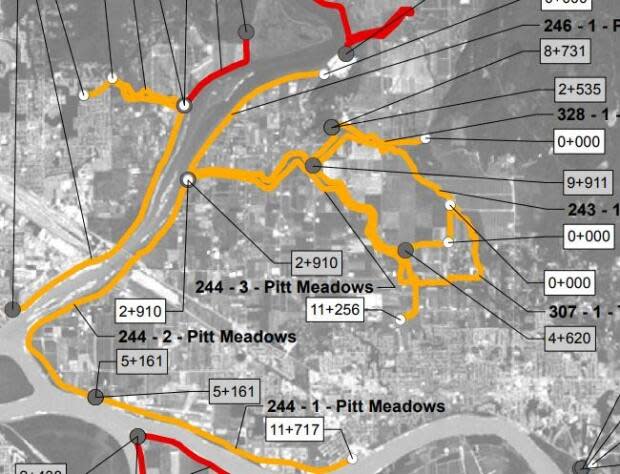

The province's 2015 report surveyed five Pitt Meadows dikes, and found of them in less than fair or poor condition — and all had a worse rating than the Sumas Lake Reclamation dike that breached this month.

While 86 per cent of Pitt Meadows is part of the region's flood plain, the municipality has historically struggled to receive funding for upgrades due to its low population base.

"Our dikes are 1930s, 1940s vintage that are not good enough," said Dingwall. "We really do need federal dollars. That's the bottom line."

What else can be done?

Flood mitigation experts say dikes aren't a silver bullet, and point to other protections municipalities can use.

They include wetland and dune restoration, changing land-use policies to limit the amount of buildings and economic activity in the most vulnerable areas, stricter regulation in hazard zones, and realigning existing dikes to leave more room for rivers to expand.

"There is this perceived safety called the 'levee effect' that makes people think, 'Once the dike goes in, we're safe, and we can overdevelop,'" said Lilia Yumagulova, who studies resilience to natural disasters and who wrote her PhD these on Metro Vancouver's flood management system.

"What are the [other] options? How can we reduce disaster risk and build more flood resilience?"

In response to questions by CBC News, the provincial government said it has spent nearly $103 million to support dike improvement and risk assessment projects since taking office, though, in a recent news conference, Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth admitted "there's more to be done," promising a new flood strategy and legislation in 2022.

In the meantime, municipalities like Pitt Meadows know they have work to do — while admitting they're playing catch up.

"We've done the homework. We know the case," said Dingwall. "Now we just need the dollars."