NASA's Voyager 2 Went Interstellar the Same Day a Solar Probe Touched the Sun

WASHINGTON — Call it a cosmic coincidence: Two probes launched four decades apart, traveled in opposite directions — and used similar instruments to gather milestone data within hours of each other.

That scientific poetry took place on Nov. 5. Without orchestrated calculations or trajectory maneuvers, the grizzled Voyager 2 probe crossed into interstellar space the same day that the freshly launched Parker Solar Probe made its first close approach to our sun. Both spacecraft were equipped with unique Faraday cup instruments, which they used to gather milestone data about nearby highly charged plasma particles streaming off the sun.

"To be crossing into new territory on both edges of the heliosphere at the same time to within a day — you couldn't plan that if you wanted to," Justin Kasper, an astrophysicist at the University of Michigan and principal investigator for the Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons, or SWEAP, instrument on the Parker Solar Probe, told Space.com here during the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, where both missions' accomplishments were conversation starters. [NASA's Parker Solar Probe Mission to the Sun in Pictures]

As a human, Kasper loved the coincidence, although as an astrophysicist he does have one small worry. "I am not going to be able to keep up with writing these papers," he said.

The differences between the two missions are staggering. They launched 41 years apart. Where Voyager 2 has enjoyed a leisurely stroll among the outer planets and beyond, the Parker Solar Probe made a mad dash to the center of our solar system in just three months. It would take nearly a quarter-million copies of the Voyager 2 computer to equal the memory of the smartphone in the pocket of a Parker Solar Probe engineer. When the Voyagers launched, bell-bottoms were hip — and they're back on the runways for Parker's first winter in orbit.

Both spacecraft are equipped with similar instruments for measuring plasma particles. That's no coincidence: Kasper was inspired in his SWEAP design by the very instruments that flew on the twin Voyager probes, which were built by his graduate-school mentors. Voyager 2 carries four larger Faraday cups all told, with three pointed at slightly different angles toward the sun; whereas Parker carries just one much smaller cup designed to sip the sun's plasma flood.

Voyager 1's Faraday suite stopped working decades before it entered interstellar space, leaving scientists to wait an extra six years for data of this type. On Nov. 5, it finally came, when Voyager 2's version of the instrument recorded the disappearance of plasma about 120 astronomical units (AU) away from the sun. (Earth is on average one AU away from the sun.)

That plasma disappearance marks the heliopause, where the solar wind — a constant stream of plasma particles flowing off the sun — collides against the superfast particles called cosmic rays that make up the interstellar wind. The resulting heliopause is a bubble that inflates and contracts over the course of the sun's cycle.

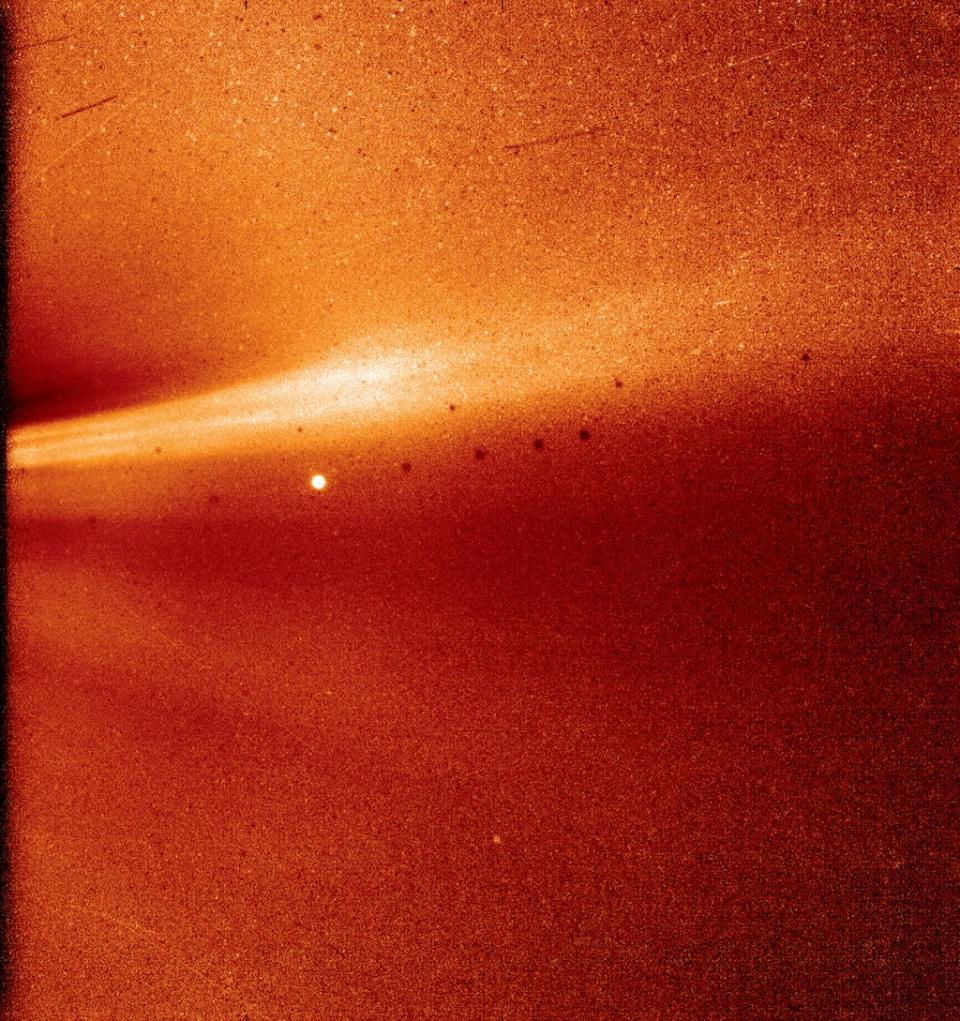

Parker Solar Probe's job is to investigate the source of that solar wind within the sun's ultrahot atmosphere, called the corona. It will do so for seven years in order to capture data at different stages of the solar cycle, making a total of 24 planned solar flybys to inch ever closer to our star. And so, on Nov. 5 at 10:28 p.m. EST (0328 GMT Nov. 6), it and its Faraday cup grazed less than one-fifth of an AU above the sun's visible surface.

And just like that, in less time than it takes humanity's home world to twirl once within the vastness of the cosmos, two of our creations brushed opposite ends of the bubble surrounding our celestial neighborhood and our fingers stretched a tiny bit deeper into the heavens.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.