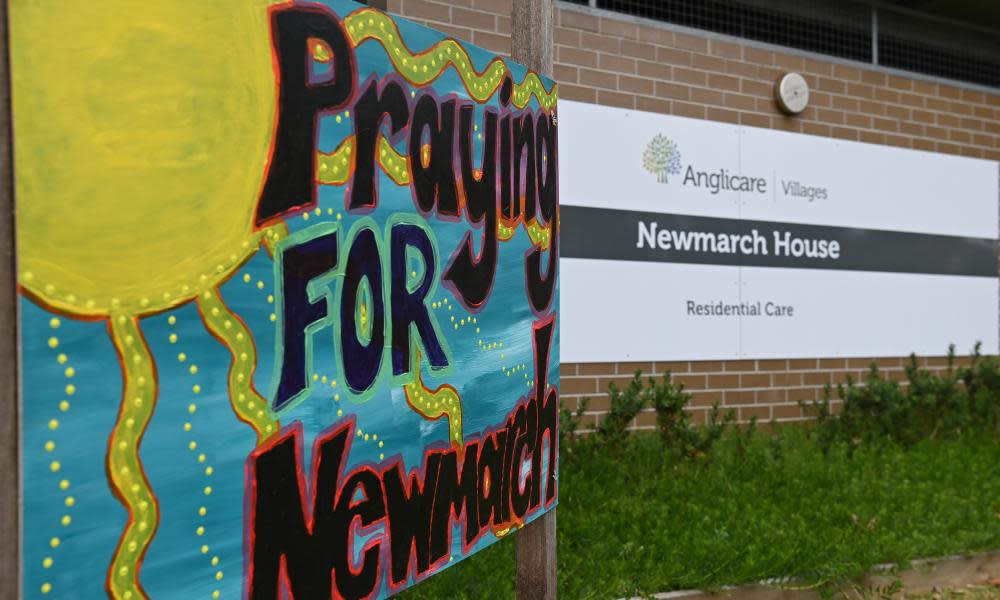

Newmarch House operator tells of Covid-19 'dysfunction' between state and federal officials

The head of Sydney’s Newmarch House aged care home has spoken out about a “frustrating level of dysfunction” between state and federal health authorities who gave conflicting advice about whether to send infected residents to hospital during the early weeks of a deadly Covid-19 outbreak.

The aged care royal commission on Tuesday heard evidence about how Newmarch House responded to the coronavirus outbreak, which resulted in 37 residents testing positive and 17 dying. The inquiry was told about the inherent infection control issues aged care facilities face if they choose to pursue a “hospital in the home” approach to treat residents in-house.

The royal commission heard Newmarch – along with all of operator Anglicare’s 22 facilities in New South Wales – had self-assessed its readiness to respond to a Covid outbreak as “best practice” less than three weeks before the first case in early April.

That assessment, the operator now acknowledges, was not accurate because they had viewed Covid-19 as a flu-like, less virulent threat, and even their conservative predictions underestimated the fact 87% of staff would need to be replaced.

The comments from Grant Millard, the chief executive of Anglicare, came after senior counsel assisting the royal commission, Peter Rozen QC, on Monday admonished the federal health department and aged care regulator for failing to develop a Covid-19 response plan for the sector – a claim the aged care minister, Richard Colbeck, and the acting chief medical officer, Paul Kelly, contested on Tuesday.

Millard also told the aged care royal commission how Anglicare was “struggling to plead” with state and federal health authorities for access to personal protective equipment stockpiles during the early weeks of its outbreak.

The commission saw an email from NSW Health on 21 April that told Newmarch staff to only use full PPE when interacting with positive and suspected cases, which Millard said conflicted with advice from James Branley, the head of infectious diseases at Nepean hospital, who said to use full PPE with every resident.

On Monday, Rozen outlined that the royal commission would hear evidence this week of an email from the aged care quality and safety commissioner Janet Anderson urging authorities to call out an “intolerable” view held by NSW Health that evacuating infected residents to hospital would set a precedent for future outbreaks.

Documents tendered before the commission also reveal Millard told an Anglicare board meeting on 6 May of a “frustrating level of dysfunction” between state and federal health authorities, and on Tuesday he elaborated, stating the conflict was “particularly intense” during the first two weeks of the Newmarch outbreak at the beginning of April.

“Everyone was clearly exercised and passionate about how this could be dealt with quickly and for the expert opinion to be declared. But it just wasn’t clear who was in a position to give that advice.”

At a later board meeting on 27 May, royal commission evidence shows Millard warned that Anglicare would be “far more assertive ... and would strongly push for these (infected) residents to be immediately transferred to hospital” in the event of a future outbreak at an Anglicare facility.

On Tuesday, Millard said the “hospital in the home” approach decided upon by the local health area network “presented a monumental challenge” due to resourcing. He said treating the residents at the facility risked infecting staff, and effectively confined all other residents to their rooms.

“I believe if we would have been able to transfer out Covid-positive residents earlier we might have had an earlier liberalisation, of what was really extremely difficult for our residents to go through, being isolated in their rooms with the doors closed,” he said.

“To run a hospital you need substantially more (staff), a greater number of registered nurses to do that. It’s just not the way a residential aged care home operates … I think if you compare the level of equipment, the resourcing, you know, it’s not reasonable to anticipate any of that level of equipment resourcing would be available in a residential aged care home. That would have to occur in a hospital,” Millard said.

Related: Moving aged care residents to multiple Melbourne hospitals amid Covid-19 'could be catastrophic'

Millard also spoke of how Newmarch was overwhelmed by staff losses during the outbreak. He said “we were all scratching around and people were scared. They were terrified of Covid-19 and it was difficult to get people.” He said that surge staff from Mable, provided by the federal government, were not trained and had little experience in aged care homes or in using PPE, and said “it was dangerous for them” to have been sent to Newmarch.

The royal commission also attempted to compare the Covid-19 responses at Newmarch House and Sydney’s Dorothy Henderson Lodge. At Newmarch, two of the infected 37 residents were transferred to hospital, where one died, while the remaining 16 deaths occurred at the facility.

However, James Branley, the head of infectious diseases at Nepean hospital and a doctor called in to help the responses at both Dorothy Henderson Lodge and Newmarch days after their first cases, defended the “hospital in the home” approach.

Earlier, the royal commission had heard of further infection control issues with “hospital in the home”, including that the litre per second per patient airflow in homes was “nowhere near” the requirement for air decontamination mandated in hospitals.

At the end of his evidence, Millard acknowledged the “incredible sacrifice” families of residents had made and expressed “regret” that Newmarch failed to communicate effectively regarding their loved ones.

“They are stressed and they want to know how their mum is, how their dad is. And it’s a struggle to do that with a completely foreign workforce in a home, wearing a face mask, who just don’t know their mum and dad. It’s very, very difficult,” he said.

Virginia Clarke earlier told the royal commission of her late father Ron Farrell’s experiences after contracting Covid-19 at Newmarch House.

She said she called the home every day for information about her 94-year-old father, and that during one such call, a staff member inadvertently mentioned he had been diagnosed with Covid-19, not realising Clarke had not been informed.

“I was in shock. I didn’t know what to say,” she said. “Nobody actually told me what treatment dad was getting.”

She said she had also been asked to revise her father’s end of life plan, and when she asked why, was told it was not because of his Covid-19 diagnosis, which she had been told was mild.

Farrell, a former air force member and father of seven, died on 19 April.

Clarke said she was forced to guess her father’s time of death because the crematorium picking up her father’s body requested that detail but Newmarch hadn’t told her.

The federal aged care minister, Richard Colbeck, on Tuesday again rejected suggestions the health department and aged care regulator didn’t have a specific plan to deal with coronavirus.

“We have had a plan to deal with Covid-19 in residential aged care going right back to the beginnings of our preparations,” Colbeck told reporters.

Australia’s acting chief medical officer, Prof Paul Kelly, also dismissed the notion there hadn’t been a plan in place, citing various reports and guidelines created since March.