Nightingale emergency coronavirus hospital may not be needed as urgently as expected

The new 4,000-bed Nightingale emergency hospital in London was opened by Prince Charles via videolink on Friday, but it is hoped it will not be needed as urgently as previously thought because hospitals in the capital are coping better with the coronavirus.

A week ago it had been thought that intensive care units in London would be overflowing by this point, but political sources said they had been told the capital’s hospitals were three-quarters full, which is better than expected.

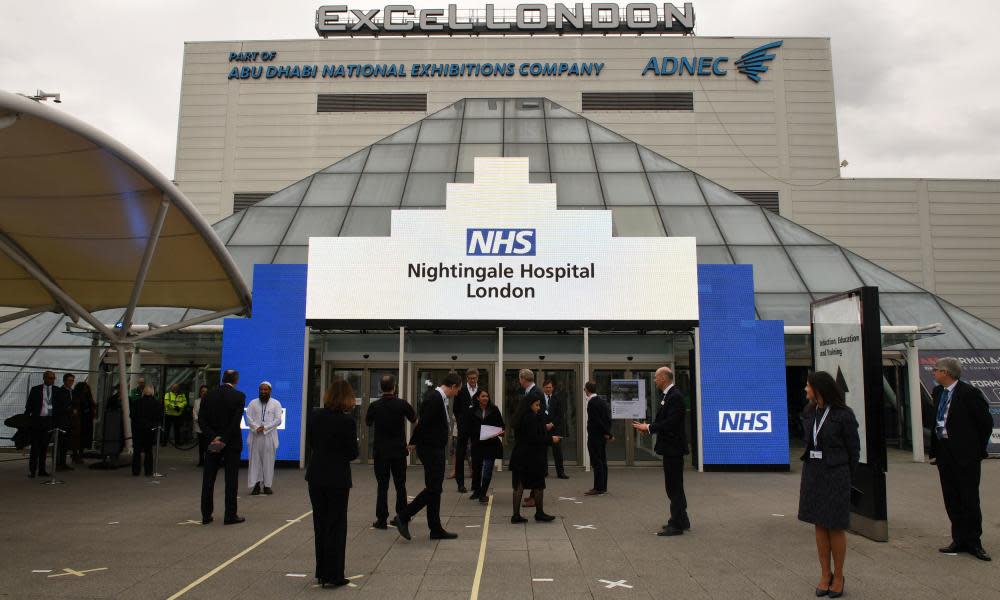

In a highly praised high-speed build involving an unprecedented partnership between the NHS and the Ministry of Defence, the vast ExCeL conference centre in east London has been converted into a hospital, ready to take up to 500 patients in the first wave.

Related: Nightingale hospital in London 'to treat less critical Covid-19 cases'

But while the emergency capacity had been expected to be required as soon as last Wednesday, the first patients are now likely to arrive early next week – a tentative sign that the coronavirus outbreak in the capital may not be as bad as expected.

An NHS spokesperson said: “Nightingale London is ready to accept patients from today, but London is currently coping with demand. We obviously can’t predict when it will be needed but it’s there if and when it is.”

Emboldened by the success of the build, civil and military planners are working on building emergency hospitals around the country, typically at conference centres, but also using universities, stadiums and leisure centres.

Facilities are being built at the NEC in Birmingham and the G-Mex centre in Manchester with an initial capacity of 500 beds each; followed by a 1,000-bed site in Bristol, at the University of the West of England; and 500 beds at the Convention Centre in Harrogate.

The SEC in Glasgow is being converted into the NHS Louisa Jordan hospital, with an initial 300 beds, rising to 1,000 if needed, while in Wales 2,000 beds are being prepared at the Principality stadium. It is not yet clear that there will be a need for emergency hospitals in north-east or south-east England.

The capital remains the centre of the coronavirus crisis in the UK, and is thought by planners to be a couple of weeks ahead of the rest of the country, although there are some signs that infections are accelerating in at least one other area, the West Midlands.

Latest figures show that across the capital, 899 people have died in hospital after testing positive for the disease. However, the Health Service Journal estimates the true figure for deaths to be 1,053, once those who died at home are included.

The new hospital in London will have up to 80 wards of 42 beds each – requiring 200 staff who will be expected to work in two 12-hour shifts to ensure patients receive the round-the-clock care required to keep them alive.

The nearby University of East London is making up to 500 rooms normally used by students available for doctors, medics and other hospital staff working on the site, shortening their commute to the emergency site.

As many as 16,000 staff will be needed, at least 500 of whom are expected to be unpaid volunteers from St John Ambulance, with cabin crew and other airline staff from Virgin Atlantic and easyJet.

One of the biggest challenges, however, will be in ensuring the large number of staff not previously trained in working with patients in a critical condition deliver effective care. Volunteers being trained to work at the site have been told they must be “prepared to see death”.

If London proves to be coping better than expected, the facility could take in patients from other parts of the country, airlifted in from more remote locations. Nearby London City airport, now closed to commercial traffic, said it was ready to be used in a military airlift or for any other emergency purpose.

With no end to the national lockdown in sight, growing concerns about the lack of progress on testing and worries about the supply of protective equipment, the nine-day build has been a bright spot in an otherwise difficult week.

Charles, himself recovering from coronavirus in Scotland, opened the hospital remotely saying it was “without doubt a spectacular and almost unbelievable feat of work” and “an example, if ever one was needed, of how the impossible can be made possible and how we can achieve the unthinkable through human will and ingenuity”.

Politicians have also praised the effort. Boris Johnson thanked everybody involved in the build, which included up to 200 soldiers a day at the height of the work. Earlier this week, Sadiq Khan was given a virtual tour of the site. “History will remember this moment,” the mayor of London said.

Simon Addyman, an associate professor of construction project management at University College London, said building Nightingale in London in less than a fortnight was “an amazing achievement, but I had no doubt we had it in us”.

The academic, who worked in construction alongside Nato in the Balkans in the late 1990s, said: “We see in disaster zones, the military and civilian groups come together in humanitarian relief. You have to ask, why do we find it so difficult to get construction projects completed on time in normal circumstances?”