No scalpel, no drill: Medical procedure to treat uncontrollable hand tremor a 'game changer'

In a room at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Brian Smith gives one last hug to his wife, Noreen.

"You're doing really well, sweetheart," he says to her.

Doctors have finished prepping the 76-year-old patient. She's clad in a blue hospital gown, her head has been shaved and metallic headgear is attached to her skull.

She's ready to be wheeled into an MRI room, where she'll undergo a procedure that her doctors believe will revolutionize the way brain diseases are treated.

Before that happens, Noreen leans into her husband for a kiss.

"Best buddy," she whispers.

Noreen Smith is among the three per cent of the Canadian population who suffer from a nervous system disorder called essential tremor. It causes uncontrollable shaking, most often in a person's hands.

Smith noticed the first signs when she was 33.

"It started developing in my dominant hand, which is my right hand," she said the day before her medical procedure from her home in Bobcaygeon, Ont.

She went to a specialist who delivered the diagnosis: essential tremor.

Just as shocking was what he said next, alluding to a high-profile actor who had the condition.

"This particular person wasn't terribly helpful because he said: 'Do you happen to know Katharine Hepburn? I'm going to give you some medication, and you can go home and get used to the idea that eventually you're going to end up looking like Katharine Hepburn.' I was devastated," says Smith.

Simple things were tough

Medication helped for the first few years.

But Smith's tremor was still severe and like others who suffer from this disorder, the shaking worsened with simple movements or everyday tasks like applying makeup or pouring a glass of water.

When Smith tried to do that, much of the water spilled into the kitchen sink. And when she attempted to put the glass to her mouth for a sip, it was virtually impossible to accomplish.

For outsiders, it's hard to watch, but her husband came to her aid and held the glass for her.

Essential tremor won't shorten Smith's life, but it was definitely affecting her quality of life.

"We're invited out to dinner and I won't go because I'm embarrassed dropping food. Even at food courts, sometimes we'd have a cup of coffee and Brian would have to hold the cup and feed me. It's so embarrassing."

All the more reason the Smiths were "absolutely elated" when they heard Noreen was considered a solid candidate for a medical procedure called "MRI-guided focussed ultrasound" technology, a treatment approved last month by Health Canada.

No scalpel, no drill

"This is a game changer," says Sunnybrook neurosurgeon Dr. Nir Lipsman. "It really changes the way we think about surgical treatments for tremor. No scalpel needed. No drill needed."

Instead, the treatment uses a more non-invasive approach. The technology allows doctors to focus ultrasound waves guided by an MRI through a patient's skull to reach an area located deep in the brain called the thalamus. The sound waves target and destroy the cells that cause the tremor.

"What we're effectively doing with this procedure, in a non-invasive way, is killing those neurons and destroying those neurons with high frequency focussed ultrasound," says Lipsman.

He is part of an international team that studied 76 patients with essential tremor in a clinical trial in 2013.

After three months of treatment, patients who received focussed ultrasound saw their tremors reduced by 47 per cent. After one year, it was a 40 per cent reduction in tremors.

That's compared to less than one per cent improvement in those who received a so-called "sham procedure" or placebo.

Side-effects included gait disturbance and numbness that decreased over one year.

The results were published today in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The technology "will open up a new era that will revolutionize the way brain diseases will be treated, eventually benefitting millions of patients," says Dr. Kullervo Hynynen, director of physical sciences at Sunnybrook Research Institute. He also helped develop the technology.

Lying inside the MRI machine last week at Sunnybrook, Smith patiently endured the four-hour procedure.

Like all other patients before her — and so far there have been about 40 at Sunnybrook — she remained awake and was closely monitored by a team of neurosurgeons and MRI technicians in a nearby room.

When it was over, when she walked out of the MRI room. Doctors removed the cumbersome helmet, she sat down and performed a few tests for Lipsman.

"Are you able to touch your nose with your index finger?" he asked. She did, guiding a steady hand to the tip of her nose.

"Couldn't do that before," she said.

She was handed a glass of water. She drank it, without a drop falling. She beamed with satisfaction.

"This is amazing."

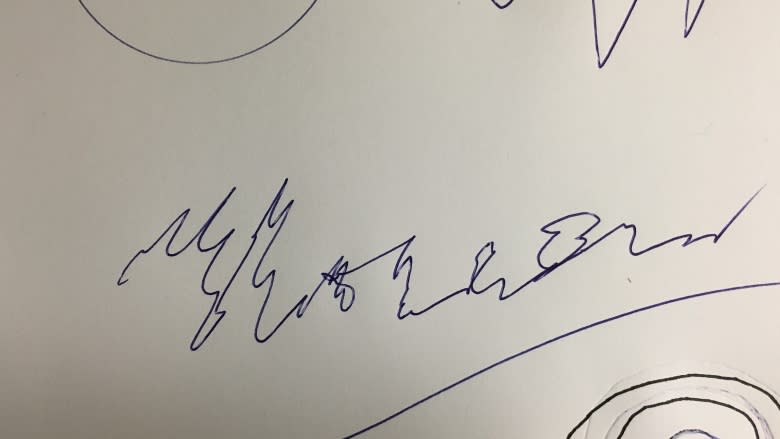

Finally, she was asked to write her name, a task that has been impossible for decades.

Her penmanship was flawless.

"Just being able to to hold my hand like that — it's miraculous."

For good measure, she rose from her wheelchair and performed an Irish jig.

Doctors hope to apply the technology in the treatment of other diseases like Parkinson's and epilepsy.

For Smith, her objectives are less grandiose: a return to her passions of gardening and art. But most of all, she looks forward to the simpler gestures between a married couple.

"I will be able to sign my husband's card for our 50th wedding anniversary," she told reporters, "which is coming up at the end of the year."

Watch CBC's Facebook Live with the team behind the surgery.