Noise pollution: What you need to know about the carbon footprint of streaming music

If you love sipping an herbal tea and munching an organic snack while you stream Spotify or Apple Music on a sleek device in your pocket, don't expect a sticker for being virtuous just yet.

It turns out your mother may have been right about your music after all: it's just a bunch of noise pollution.

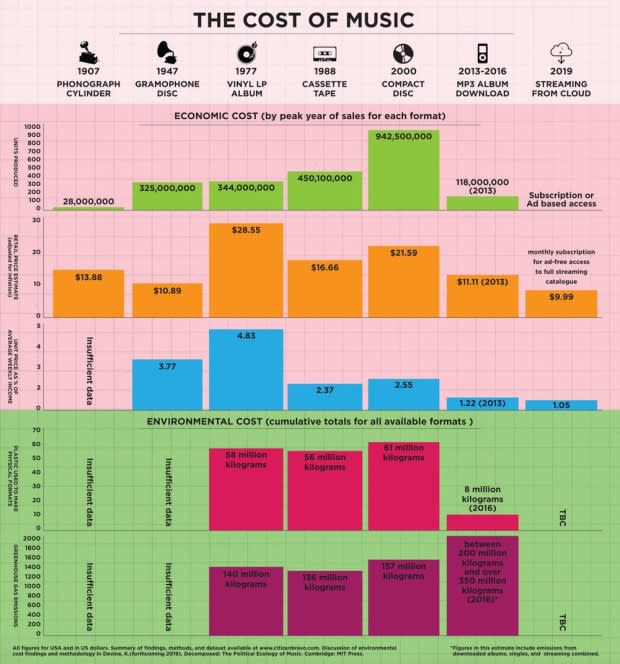

Researchers at the University of Oslo and the University of Glasgow, in a joint study titled The Cost of Music, have determined that streaming music is worse for the environment than vinyl or CDs.

Musicologists Kyle Devine and Matt Brennan studied the consumption of music through the decades, choosing key years based on U.S. record sales.

They chose 1977 as the peak of vinyl sales, 1988 as the peak of cassettes, 2000 as the top-selling year for compact discs, and 2016 to focus on the downloading and streaming of music.

They analyzed the amount of plastics used to make each format, with levels averaging between 56 million kilograms to 61 million kilograms in the earliest years.

The carbon footprint of listening to recorded music might actually be higher today than ever before. - Kyle Devine

As expected, with consumers ditching physical music for streaming music, the level of plastics used has dropped dramatically in recent years — 8 million kilograms in 2016.

But when they measured the greenhouse gases it took to make the music of the each year, the results surprised them.

"The carbon footprint of listening to recorded music might actually be higher today than ever before," says Devine.

Greenhouse gas emissions for streaming and downloading in 2016 were between 200 million and 350 million kilograms — over 50 million kilograms more than the peak year of CDs.

Devine says a significant amount of that comes from the way streaming services power their servers, which often use coal, nuclear energy and gas as their major power sources.

But he also notes the history of music recording has a harsh past.

The shellac era

His research looked into the ecology of music, comparing the materials used to make recording like gramophone discs, vinyl LPs, cassettes and compact discs.

In what was known as the shellac era, from 1900 to 1950, most recordings were made with bug-based resin mostly from India. The material was harvested and processed largely by women and children, according to a 1946 report by the Indian government on the working conditions in the shellac industry.

"The report didn't mince words. It called it sweated labour, and this material is present in every record that was ever released during that period," said Devine.

Then came plastics, with recordings made with oil-based products.

Compact discs are made of a highly processed plastic that takes over a million years to decompose and contains Bisphenol A, or BPA, a chemical found to affect brain and behaviour in children.

CDs can be recycled, but there is currently no consumer recycling program in Newfoundland and Labrador.

CDs are a triple-plastic challenge

Greentec International, an e-waste company based in Cambridge, Ont., recycles electronics and data for large companies, including CDs.

The company's president and CEO, Tony Perrotta, says it can be time-consuming to recycle the materials used to make CDs for reuse.

"You have the jewel case, which is made up of a polystyrene type of material. And then you'd have the actual insert, made of some type of paper stock or fibre. And then you have the actual disc, which is made of polycarbonate."

Perrotta says it's important we all put in an effort for the environment.

"The municipalities and the blue box programs need to evolve to allow consumers to add these product streams to their recycling streams," he said.

Devine says his work isn't to make others feel guilty, but to start a conversation.

"I think for a lot of people (we're thinking about this) for the first time. Certainly, for me it was the first time," he said. "So there's a positive message — by the very fact that we're already discussing it, we've already started to do something about it."

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador