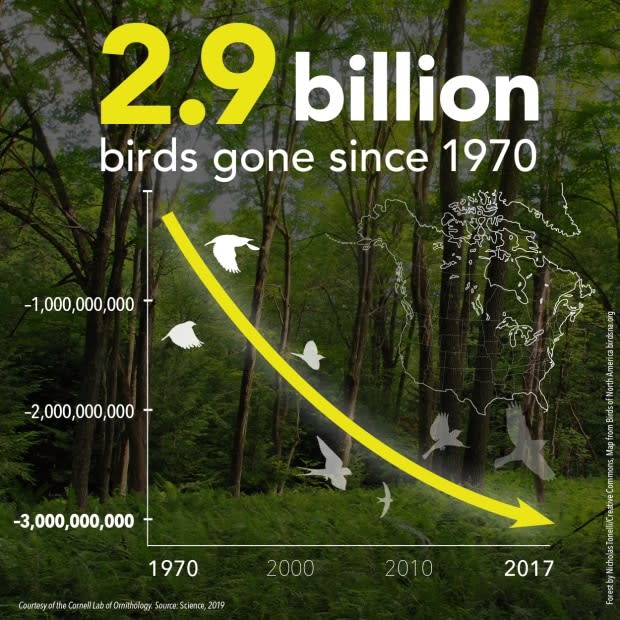

North America has lost 3 billion birds since 1970

There are nearly three billion fewer birds in Canada and the United States than there were half a century ago, a new study estimates.

It counted a loss of 2.9 billion birds compared with 1970, which represents a population decline of 29 per cent and an "overlooked biodiversity crisis," said the report published Thursday in the journal Science.

"I was stunned," said Ken Rosenberg, the lead author. "I couldn't believe that there was that magnitude of a net change."

Rosenberg is a conservation scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the American Bird Conservancy.

His study with Canadian and U.S. collaborators combined population data from more than 500 species going back half a century. It also includes a decade of weather radar data that measures the mass of migrating birds, and found a 14 per cent decline over that time.

The study found that the vast majority of the birds that have disappeared aren't rare or vulnerable endangered species, but include many familiar backyard birds like sparrows, juncos, and starlings considered common and abundant.

"That is what is such a strong indicator that something is wrong in these habitats and environments," Rosenberg said. "This loss of abundance is so pervasive that it's the old canary in a coal mine — it's almost certainly an indicator of a degradation of overall environmental quality that's ultimately going to affect people."

The study noted that birds provide important benefits to ecosystems, such as pest control, pollination and seed dispersal, and warned that common birds may be disproportionately important parts of the food web and local ecosystems.

Previous reports, such as the State of Canada's Birds earlier this year, showed that some groups of birds, including grassland birds and shorebirds such as plovers and sandpipers, have declining populations. A report on the State of North America's birds in 2016 had even estimated that bird populations had declined by a billion since 1970.

Andrew Couturier, a senior director with Bird Studies Canada, one of the groups that produced those reports, said those reports were based on relative population changes rather than actual counts. He's confident in the improved estimate based on improved and refined data and methods, which Bird Studies Canada was not involved in.

Couturier called the new estimate "shocking" but says it matches up with what many people have reported anecdotally: "This is kind of confirming what we've noticed."

Previous studies also showed that some groups of birds, such as waterfowl and birds of prey, were increasing, largely due to conservation measures.

Rosenberg thought an actual count of bird populations in North America over time might show growing populations for some species partly compensating for population losses among declining species, many of which are rare to begin with.

To his surprise, that wasn't the case. The new study showed even birds such as house sparrows and starlings, which were introduced from Europe, do well in cities, and have typically out-competed native birds, are disappearing — their populations are down 331 million and 83 million, respectively, since 1970.

People love birds. There's an army of people out there who love to go out and do these surveys and count birds. - Ken Rosenberg, lead author

Rosenberg said even backyard birds that aren't choosy about their habitats can be affected by degradation such as intensifying agriculture, urban sprawl, and fragmentation of forests. They also face other human-caused threats, such as increased pesticide use, domestic cats, and collisions with windows.

"It's what we call death by a thousand cuts," Rosenberg said.

The report found native sparrows, warblers and blackbirds have seen some of the biggest population declines, in the hundreds of millions of individuals.

Paul Smith, a research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada who co-authored the paper, said those aren't necessarily the most worrying declines: "They're just the largest in magnitude, because those species started with large population sizes."

Birds that migrate long distances, such as those shorebirds that Smith studies and many of those that breed in Canada's Arctic or boreal forest but spend winters in Central and South America, have been particularly hard hit. Migrating species declined by 2.5 billion individuals, faring much worse than those that stay put year round, that increased slightly, by 26 million.

"Canada, and in particular Arctic Canada, is the breeding range for a lot of North America's shorebirds. So really Canada has a huge responsibility for the conservation of these birds."

The study points out that conservation has brought back populations of waterfowl.

"What we've found," said Smith, "is when we've put our mind to it, we've been able to recover species."

That said, Couturier noted that 80 per cent of Canada's birds spend part of the year outside the country, meaning that we need to work with partners in the U.S., Mexico and Central and South America.

Beyond birds

Birds are particularly good indicators of ecosystem health as they are easier to monitor than another other group of animals, the researchers note. They're active during the day, and are conspicuous, making it possible for people to both see and hear them, Rosenberg said, unlike many insects, lizards or mammals.

The population estimates in the study largely made use of data collected by volunteers or "citizen scientists" during standardized annual surveys, especially the Breeding Bird Survey, which has been running since 1966, coordinated by Environment and Climate Change Canada's Canadian Wildlife Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and Mexico's National Commission for Knowledge and the Use of Biodiversity.

"People love birds," Rosenberg said. "There's an army of people out there who love to go out and do these surveys and count birds."

Bridget Stutchbury, a York University professor of conservation biology and ecology who studies migratory songbirds in North America but was not involved in the study, called the results "alarming."

"This is the first ever 'big picture' of overall bird losses, and it uses two independent data sets to make the case that we are still in the midst of a bird decline crisis," she said in an email.

However, she noted the study wasn't designed to address the root causes.

"So while it is a call to arms, it's a bit unclear what new or stronger direction we should take as a society."

The researchers and the bird conservation and research groups they belong to do offer suggestions for individual and policy actions that could help through their website 3billionbirds.org.

A UN report earlier this year found not just birds are in decline: one million species of plants and animals are at risk of extinction, half of them due to "insufficient habitat for long-term survival." Kai Chan, a professor at the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia who co-authored the report, said the new study had more precise population estimates for birds.

And while it doesn't directly say anything about the decline in other species, what is bad for birds is often bad for other animals, and some of the bird declines may be reflecting the decline in prey species such as insects.

"It further confirms what we already know," he said in an email. "The big picture is very concerning."

Other studies have looked at recent declines in groups such as amphibians and insects. One recent report showed that many bumblebee species are declining in Canada.Victoria MacPhail, a bee specialist at York University and lead author of that report, said she was "equal parts shocked and not all that surprised" by the bird population decline.

She said monitoring populations of animals needs to continue, and the public can help by participating in citizen science.

"But we also need to take action on the ground with increased conservation efforts and behaviour changes and in the halls of government, with changes in policy and regulations and even an increase in funding support: simply lamenting the loss of our biodiversity will not cause anything to change."