Nostalgia flows as AFL's State of Origin returns for bushfire relief match

Back when footy was mainly an inner-suburban affair and when crossing state borders was like entering a different hemisphere, there was State of Origin football, and it was very big indeed.

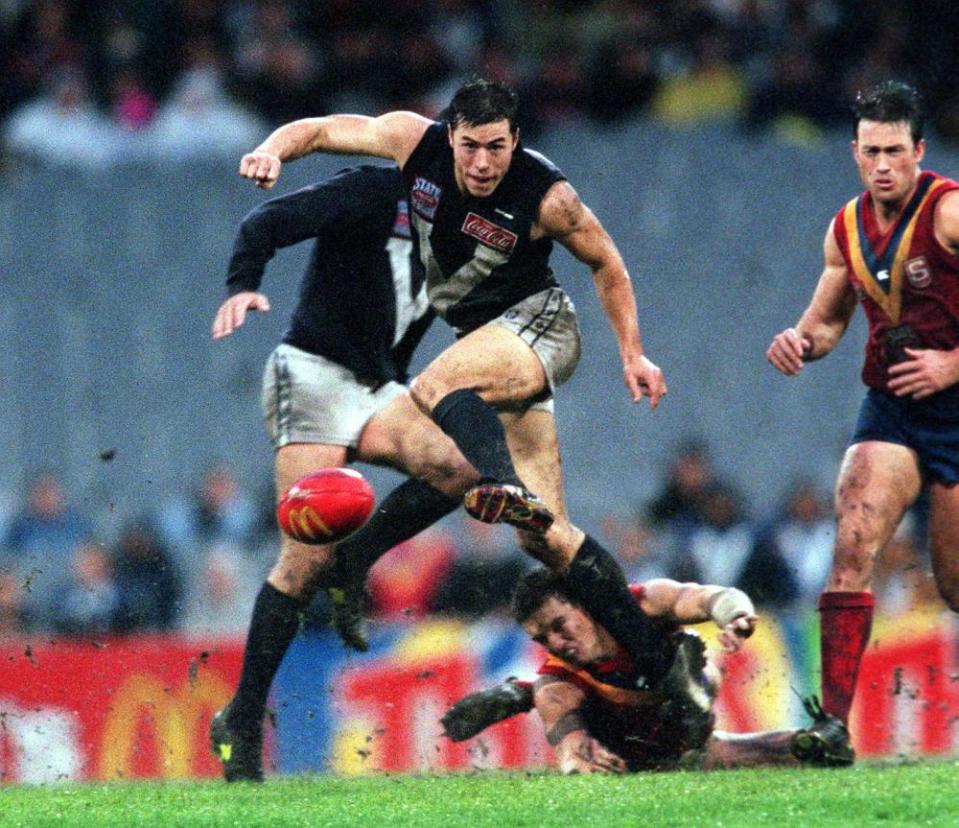

There had always been state football of course. For decades, it was essentially competition versus competition. Interest levels varied from year to year. Some games were buried away in the post-season, attracted meagre crowds and were quickly forgotten. But for a few years, just as football went truly national, just as the various state leagues began to flounder, just as floodlights started being erected around Australia, and just as some of the game’s biggest names embraced the concept, it showcased some of the best football ever played.

Related: The Joy of Six: Great AFL pre-season moments

In light of Friday’s bushfire relief game in Melbourne’s Docklands, this column is mainly concerned with memories pertaining to the Big V. As a result, many of those memories are bittersweet. Too often, the talent-laden Victorian sides came a cropper. In 1990, when they were beaten by New South Wales, it was like losing to Greenland in a Test cricket match. “State of Embarrassment” was the headline in The Age.

But it is the games against South Australia and Western Australia that really stick in the memory. You always got the sense that State of Origin football meant that little bit more to them. The Victorian clubs had been pinching their best players for years. Their local competitions were slowly dying. They had a lot to prove.

“The South Australians distrusted the imperialistic and arrogant way the Victorians conducted their football,” Gary Linnell wrote in Football Ltd. A State of Origin win, he wrote, “was celebrated with the sort of gusto and pride normally reserved for a gold medal performance at the Olympic Games.”

The South Australian crowds were utterly bonkers and preternaturally parochial. They’d shriek whenever a Croweater gathered possession. They all spoke with strange, clipped, borderline Kiwi accents. Even the Football Park siren was ridiculous. It suggested an imminent attack from the Luftwaffe. The South Australians had big bruisers with Bavarian sounding names - John Schneebichler, Grenville Dietrich and Rudi Mandemaker. But they cultivated a ballistic, hard-running game that utilised the space of Football Park.

Similarly, the Western Australians often seemed to be playing a different version of the sport to the Victorians. They were lightly framed and fleet of foot. They played on Tuesday afternoons and a sizeable percentage of the crowd wagged school and chucked sickies to attend.

If you were to take a superficial stab at 10 of the best games ever played, several state games from the 1980s and early 1990s would warrant serious consideration. The 1986 clash between Western Australia and Victoria would be a certainty. So too, would the 1994 game between South Australia and Victoria (in the commentary box, Don Scott verged on being impressed). Indeed, it’s hard to imagine that football has ever been played at a higher standard at it was that night.

State of Origin games were almost always shootouts. They were played at breakneck speed. And they left some enduring memories. There was the sorcery of Darren Jarman in the MCG mist in 1993, a harbinger of things to come. Two years later, there was Ted Whitten – blind, dying and still baying for South Australian blood. There was the Lockett and Dunstall show in 1989. There was Tony Hall buckling his knee in the MCG bog and kicking one of the great goals three years later. There was Dermott Brereton swaggering on after half-time in his fluoro green boots. (He wanted to wear a pink pair – “over my dead body are you going to play for Victoria in them,” Whitten bellowed.)

“I drive a Ferrari about 50km to state training and I suppose I pass about a hundred thousand people at train stations,” Brereton said in 1988. “It really is an honour to be chosen to represent them.” It’s an extraordinary image to ponder – this barrel-chested, sparrow-legged and sharp-elbowed man whizzing by the commuters at Kananook and Caulfield, silently vowing to do them proud. But that was Derm. And that’s how big State of Origin footy was.

It certainly unearthed some stupendous talents. In 1984, Gary Ablett had played just nine games for Geelong. Coach Allan Jeans was reluctant to select him. He barely said boo to his teammates. They called him Muttley. He booted eight goals from the half forward flank and football was never the same again. That same year, Steve Kernahan announced himself to the wider footballing public, kicking 10 goals in a losing side. Several years later, Wayne Carey emerged as a superstar at Football Park.

Mopping up at Carey’s feet that night was a scruffy looking little fellow named Adam Saliba. He played just three games of league football. Legend has it that his career was cut short when he skipped training and crossed the border for the infamous Guns N’ Roses concert at Calder Park. The concert was a fully-fledged fiasco. It was about 42C and there wasn’t a scrap of shade. Local hoods commandeered the water supply and were selling bottled water for $30 a pop. People were drinking toilet water and robbing Mr Whippy vans. It prompted a Victorian Ombudsman investigation. Saliba was never seen again.

Many of the big names of that golden era – Whitten, Frawley and Stynes – are sadly no longer with us. Football Park has been demolished. In the end, State of Origin had run its race. The Eagles and Crows fielded virtual state sides anyway. The stars faked injuries. The crowds lost interest. The concept died away.

Friday night is a fundraiser, an exhibition game, an appetite whetter. But there’s something about that Big V jumper and something about a representative side groaning with talent. It represents the cream of football’s crop, and is sure to get the nostalgic juices flowing.