Not surprising, but 'very important': Liberation therapy creator disproves own research

A controversial treatment for multiple sclerosis that appeared in 2009 has now been established as ineffective by its own inventor.

The so-called "liberation therapy" was created by Italian doctor Paolo Zamboni. His hypothesis was that the veins in the head and neck of those living with MS narrowed and were blocked, causing blood to back up in the brain. His solution was to dilate the veins to help drain the blood.

Media reports followed, and thousands of people in Canada looking for relief signed up for the therapy, which was only offered abroad because it wasn't approved in Canada.

In November, though, Zamboni published a new study in the journal JAMA Neurology, which found no improvement in patients with MS who underwent liberation therapy, calling it "largely ineffective" and not to be recommended.

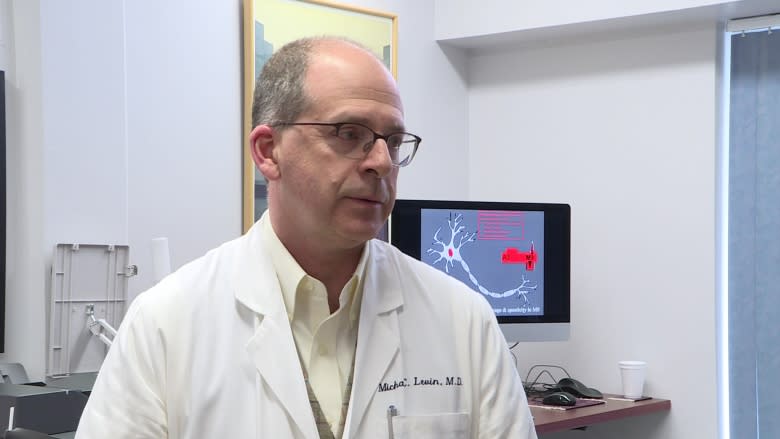

"I don't think it's surprising but I think it's very important," said Dr. Michael Levin, the MS research chair at the University of Saskatchewan.

He says the study found "there was really no difference between people with MS who got the procedure and people with MS who got a sham procedure where they put a catheter in those people but just did not open up their veins."

The incidence of multiple sclerosis is higher in Saskatchewan than any other province in Canada, and Premier Brad Wall and his government even endorsed and funded research into the liberation therapy treatment.

Therapy still gives hope to some patients

Jacquie Sivertson accepts that liberation therapy won't work for every MS patient, but she believes it worked for her.

"Almost immediately, when I got out of the hospital, I could walk further than I had in a long time," she said.

"That last four-and-a-half years, I had way more strength and energy."

Sivertson, who is 65 and was diagnosed with MS in 1988, received the treatment in Bulgaria in 2010 and says she experienced relief from many of her symptoms for years after the treatment.

Then, she was diagnosed with cancer and underwent chemotherapy.

"My symptoms acted up. My MS has taken away the use of my legs, totally."

Where Sivertson used to use a walker, she now uses a wheelchair and feels more fatigued. She believes the chemotherapy set her back.

If she could afford to travel to Bulgaria for the surgery again, she says she would.

"It definitely doesn't work for everybody. I have friends that had it, and it didn't work for, and friends that had it that it does work for. Some saw improvement, but it only lasted weeks for them."

Closer to a cure

Dr. Levin would not recommend that liberation therapy patients undergo the same treatment again, but he does want to hear from them.

"I believe, philosophically, that people with MS will help cure MS. There's going to be something in the environment, or someone will tell me something at the clinic that will give us a clue."

Levin says doctors now have a better understanding of the issues that accompany MS, like difficulty with walking and with urine control.

"The infrastructure is relatively new in the last 25 years, so it's a real hopeful time."

A multiple sclerosis diagnosis means something very different than it did 20 years ago, when there were no medications to treat the autoimmune disease. Now, there are more than 10.

Levin will hold his position at the University of Saskatchewan for at least seven years, and hopes to make progress toward a cure during that time.

He has a message for people in Saskatchewan who have been diagnosed.

"I would say to people with MS, please come [to the clinic] and please come early."