What now for the BBC?

So Charles Moore isn’t going to be chairman of the BBC after all. Perhaps he withdrew because he was upset by Julian Knight MP, Conservative chair of the digital, culture, media and sport select committee, saying that appointing him would be like a convicted fraudster running a bank. Perhaps it was the money: one story goes that he had negotiated for nearly three times what the current chairman Sir David Clementi is paid. Will we ever know? That’s not to say there’s no other speculation. Kelvin MacKenzie, former editor of the Sun, is apparently applying and, if appointed, he says the first thing he’d do would be to sack Emily Maitlis.

There was even talk of appointing George Osborne as chairman, the man who has done more harm to the BBC than anyone, before he ruled himself out. And there remains the possibility of Paul Dacre using his forthright turns of phrase at the morning briefings of regulator Ofcom, with its higher ranks of economists and former Whitehall mandarins. I can’t quite see it. Yet even if none of the most notorious BBC-haters ends up in either chair, the act of trailing their names before the start of the appointment process may well have deterred some candidates from applying.

On 27 September an article in the Times quoted an anonymous government source who said an “all out war” is “being waged on the broadcaster by the government … the most concerted attack it has ever faced”. In February Tim Shipman in a Sunday Times piece also quoted an anonymous “government source” saying they would “whack” the BBC licence fee: “We are not bluffing on the licence fee. We are having a consultation and we will whack it.”

When exactly did that language creep into government briefings? What other parts of the constitution need whacking? The judiciary? The civil service? Parliament? The Electoral Commission? Nonetheless, the recent stories centring on Moore and Dacre – widely attributed to Dominic Cummings – did their job. They thoroughly gaslighted the BBC and its many supporters.

The only real qualification either Moore or Dacre had was that they hated the BBC and constantly said so. They weren’t just “critics”, as they were described. Nor was their “Conservatism” important – the BBC has had many Conservative chairmen. These jobs have never been reserved for “liberals”; rather the opposite.

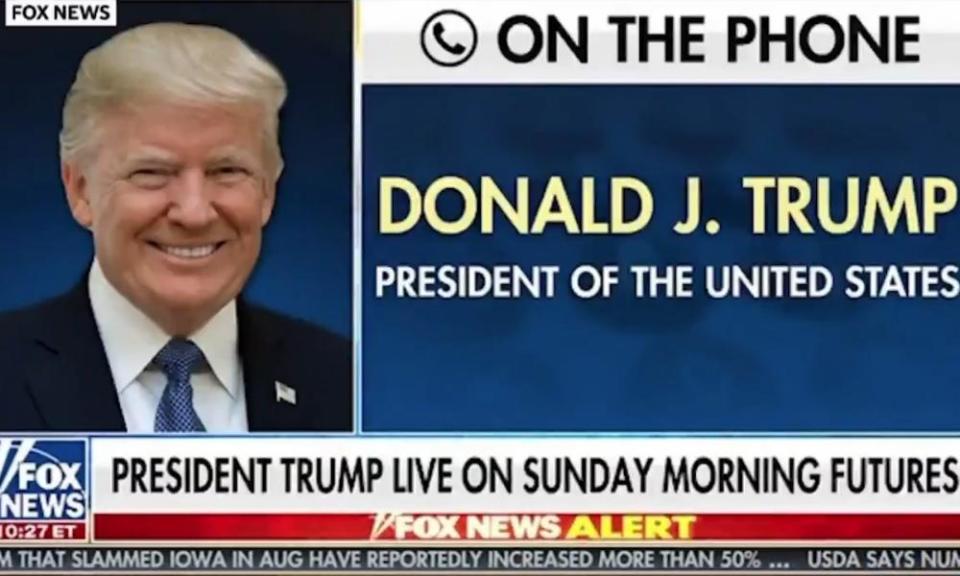

The story was intended to put the wind up some people and enthuse others. It is all part of the new way this government does things – a Trumpish pre-emptive kind of rumour, followed by a vague not-quite-denial from an official source – in this case the culture secretary Oliver Dowden.

But the newly intensified attacks against the BBC are real, and the attacker is the government. This PM seems to be the most hostile towards the BBC of any in living memory – including Margaret Thatcher.

The threats to the corporation are piling up: they include its taking financial responsibility for the (£750m) free TV licence-fee concession for the over 75s. This responsibility was palmed off on the BBC from what was originally a central government welfare payment – like the two billion a year winter fuel allowance – in a secret process by the then chancellor Osborne in 2015 with no public consultation, but six meetings between Osborne’s team and Rupert Murdoch’s. If the BBC is forced to pay the whole sum it will face drastic cuts.

And there’s another “whack” potentially due. The government wants to decriminalise non-payment of the licence fee – which would cost the corporation at the very least £200m. Only five years ago, a Conservative-commissioned independent review rejected the idea, but the government set up a new public consultation. (Though that closed over six months ago, it mysteriously hasn’t reported yet.) And then Ofcom is about to review the BBC Sounds radio streaming initiative for competitive impact, just months after they’d said the BBC should do more to engage younger audiences.

People want to destroy the BBC to create a US-style media ecology in the UK – and they think their time has come

The world’s most admired and successful public service broadcaster now faces hits to its income of anywhere between £500m and £1bn. (A billion would be around a third of its current public funding.) And the recent attacks come on top of far deeper cuts than people have realised. In March 2020, consumer group Voice of the Listener & Viewer (VLV) analysed the BBC’s finances. The results are astonishing: since 2010, Osborne’s funding cuts have reduced the net public funding of the BBC’s UK services by 30% in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. It’s remarkable that the BBC’s services have held up so well in the circumstances.

Using VLV’s figures, the net public funding of the BBC’s UK services in 2019-20 was £3,203m. In 2010-11 it was £4,580m in the same (2019-20) money. If the BBC’s public funding had merely kept pace with inflation, it would be 43% – nearly £1.4bn – higher than it is now.

Against this background of cuts, the cultural skirmishes we’re used to between the BBC and politicians have become all out war. There are people who aren’t ashamed to say that they want to destroy the BBC and create a full-on American-style media ecology in the UK – and who think their time has come. The context is the surge in rightwing populism and its emotive hot-button campaigning, combined with certain toxic effects of the internet, and finally the increasing influence of American political techniques of all kinds. We know now that this particular war has been planned for some time – in fact since 2004.

As the Guardian has revealed, in a 2004 blog from his shortlived thinktank New Frontiers Foundation, Cummings set out his plan to discredit the BBC and create a new US style media landscape in the UK. His objective wasn’t veiled in conventional thinktank talk about free markets or other abstractions. Achieving the goal was essential, he said, if the Conservatives were to gain and hold on to power, because he believed – in paranoid fashion – the BBC was the “mortal enemy” of the party.

The inspiration he cited was work done by the American right – financed by the fossil-fuel billionaire Koch brothers and their billionaire friends – to discredit the US “liberal” mainstream media and shift the US political centre of gravity rightwards – as documented in Jane Mayer’s superb book Dark Money. According to Cummings: “The right should be aiming for the end of the BBC in its current form.”

The BBC, Cummings wrote, had to be discredited by a combination of monitoring and perpetual trolling, including leaks and “stings”. And then a brave new world could be built in the UK. This world would have three key elements. The first was a Fox News type partisan rightwing TV broadcaster. The second was the kind of shock jock phone-in radio station you find all over America – which made stars of Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck. Finally, the UK should remove the barriers to big money political campaigning as they had in America. This would mean that, say, billionaire Conservative supporters such as Lord Ashcroft could buy political advertising in TV ad breaks, and make politics a game for the super-rich.

It was a strikingly modern plan for 2004. And Cummings advised that – because establishing new broadcasters and changing the law would be highly visible, contested and expensive – the right should get on with discrediting the BBC straight away, quietly online. At the time he was an outlying rightwing campaigner; now he is chief strategist, and there’s every sign that the plan is being put into effect.

Research shows people certainly trust the BBC far more that they trust the politicians and rightwing newspapers telling them not to

Researching the war against the BBC, my co-author Patrick Barwise and I were struck by how intensively the corporation appeared to be “trolled” online – both on excitably named websites such as Biased BBC and on YouTube. Apparently far away from the smart Westminster political world of MPs, journalists and SW1 thinktanks, there was a raucous world of people who ranted about the BBC as “commies”, and sometimes “paedos” and “goons”. The point of such “Astroturf” (fake grassroots) campaigns is to convince the world that a minority, partisan and planted view is a widely held natural one – something “real” people are very worried about.

The latest seems to be “Defund the BBC”, a campaign that grew earlier this year, in June, from a Tweet coming from James Yucel “just a student in his room” reacting to the “defund the police” demand from Black Lives Matter. Yucel turned out to be a media-experienced Conservative activist working as an intern for a Tory MP. And an analysis of the online spread of the campaign suggested that its astonishingly rapid growth and generous initial fundraising was anything but random. Now, four months later “Defund the BBC” has employees from Westminster thinktank land, proper funds, and is putting up posters attacking the corporation.

There are at least two Fox News-like plans for rightwing broadcasters under way – one, News GB, to be chaired by Andrew Neil, has already had investment from the American Discovery Channel. Rupert Murdoch, the owner of the Trump-supporting Fox News in the US, is also reported to be planning a UK TV news service.

•••

During our research we kept hearing deep and damaging misunderstandings about the BBC – myths, endlessly repeated by people who either should know better, or really did know better and were deliberately spreading lies. Such people were often connected to opaquely funded Westminster thinktanks, rightwing newspapers and grumpy reactionary politicians. The misconceptions can be divided into two categories: complete myths and widely held but doubtful beliefs.

The complete myths:

1 “Lots of people don’t use the BBC but are still forced to pay the licence fee or go to prison.” In reality, only a tiny (although unknown) number of households pay for the BBC yet use none of its services – unlike with many other public services that cost much more. The £157.50 licence fee (43p per day) gives every household member unlimited access to all the BBC’s services for a whole year. The only time the BBC’s total household reach has been measured, in 2015, 99% of households used it in just a single week. No one is jailed for licence-fee evasion. The Conservative-commissioned 2015 Perry review recommended against decriminalising licence-fee evasion, describing the current system as “broadly fair and proportionate”.

2 “The BBC is bloated, wasteful and inefficient.” Not according to the data. The corporation puts most of its income into content – mainly original UK content (in which it’s by far the biggest investor) and distribution. Its overheads are actually below the average for media and telecommunications companies.

3 “It’s the best-funded public broadcaster in the world.” No, it isn’t: both Japan’s NHK and Germany’s ARD both receive more public funding.

4 “It does things that should be left to the market – crowding out competitors and actually reducing choice.” But studies of the BBC’s market impact have consistently found it to be minimal and nowhere near enough to reduce overall choice.

5 “In 2015, it agreed to fund free TV licences for all over-75s but has now reneged on that agreement.” This is simply untrue.

6 “If it didn’t overpay its senior managers and star presenters, it could pay much or most of the cost of free TV licences for all over-75s.” This, too, is wildly untrue. The BBC generally pays its managers and presenters less than the market rate. If, nevertheless, it cut to £150,000 per annum the pay of everyone currently paid more than that, the annual saving would be only £20m – less than 3% of the £750m annual cost of free TV licences for all over-75s. Which services should it cut to cover the other 97%?

The three widely held beliefs that are mostly untrue:

1 “Its news and current affairs coverage is systematically leftwing.” The evidence from independent academic research is that the BBC constantly strives to be impartial in its political coverage and, when it departs from this, it tends towards over-representing the establishment, right-leaning view – increasingly so over the last 10 years. Its coverage tends to be biased in favour of the government of the day, but more so when the Conservatives are in power.

2 “It’s anti-Brexit.” The only evidence of systematic anti-Brexit BBC bias comes from the opaquely funded monitoring organisation News-watch, which never publishes its methods and results in peer-reviewed journals and never debates them. Independent academic research reaches very different conclusions, suggesting that the BBC’s coverage was largely impartial both before and after the 2016 EU referendum – and when it was not, it marginally favoured Leave rather than Remain.

3 “People no longer trust it.” Despite decades of constant attack from rightwing media, politicians, rightwing Westminster thinktanks and, now, shadowy websites and channels, the BBC remains by far the nation’s most trusted news source. Research shows people certainly trust it far more that they trust the politicians and rightwing newspapers telling them not to.

•••

The positive case for the BBC is familiar: it creates social cohesion within the country – “One Nation” – and develops the UK’s “soft power” externally – “Global Britain”. Both things are, we are told, important to this prime minister. Without the BBC we would be more fragmented, we wouldn’t share the same realities, we would be more vulnerable to disinformation and polarisation.

Recent research from the University of Zurich examined the factors that make nations more or less “resilient” to sweeping disinformation, such as conspiracy theories. One key resilience factor is the existence of an independent public service national broadcaster at scale, such as the BBC. The US – nearly off the researchers’ scale in its vulnerability to such conspiracy theories as QAnon – has never had an equivalent-sized public service broadcaster.

The BBC has had a good lockdown – the nation trusted it to tell the truth about the crisis, and its news programmes’ ratings shot up. And, over the months, attitudes to “public service” changed too. People talked about “our NHS”. Even the influential Institute of Economic Affairs, a constant critic of the NHS’s funding and advocate of increased market involvement (and, no coincidence, a consistent critic of the BBC), toned it down over the period – it just wasn’t a good look.

The BBC is publicly owned (but not state-owned or the “government broadcaster”), not owned by City shareholders, private equity or mysterious interests headquartered in overseas tax havens. It’s fascinating how many of the BBC’s opponents, those who accuse the corporation of being unpatriotic, are themselves based offshore.

The powerful economic case for the BBC is less well known. It simply spends far more on British TV content than anyone else. It has pump-primed the development of the creative industries since the second world war. And its constant inventiveness, from programmes (Killing Eve, I May Destroy You) to technology – such as developing the iPlayer when Netflix was practically a baby Blockbuster – has raised Britain’s game. The BBC ups its competitors’ games too, it obliges them to invest more in local content.

There’s a lot that needs fixing at the BBC. But it’s not what its enemies say (obsessive wokeness, or its alleged metropolitan worldview: half its employees are outside London, and the numbers are rising). It’s the historical timidity and caution at the corporation’s centre – understandable after all the bashings from successive governments. It’s the avoidance of stories that annoy governments, with the “burden of proof” excuse.

There is a case for thinking through the licence fee arrangements as the world changes, but it’s not as urgent as the BBC’s enemies pretend. There needs to be a properly independent review, driven by public interest, not the commercial interests of its global billionaire competitors or the paranoia of its political enemies. Whatever happens, the BBC needs to be made politician-proof. Since its foundation it has suffered from an ambiguous relationship with government, which has made it susceptible to political pressure through its funding. As the current war against the BBC escalates, it needs to get the hands of government from around its neck.

• The War Against the BBC by Patrick Barwise and Peter York is published by Penguin on 26 November.