Now that Quebec's new language law has been adopted, many wonder how it will be enforced

The potential problems with enforcing the Quebec government's new law to protect the French language — commonly known as Bill 96 — become evident when one imagines the simplest of scenarios.

Suppose your recycling bin is cracked, and you want to get a new one.

If you live in Montreal, you'd call the 311 information number.

But if you want to speak English with the operator, things become more complicated.

Under the new law almost all government services (with the exception of health care) must be provided in French.

There are two categories of people who will still be entitled to receive service in English or other languages: so-called "historic" anglophones (people who were educated in English), and immigrants who've been in Quebec for less than six months.

The city of Montreal has been wondering what its 311 operators are supposed to do when they're asked about a new recycling bin — or anything else — in English.

"How is one supposed to know who's entitled to receive services in English when they call 311? How is the person who answers the phone call going to be able to verify how we can implement the law?" Dominique Ollivier, the head of Montreal's executive committee, said in an interview with CBC.

Ollivier said the city fully endorses the spirit of the new law, but it's waiting for answers on its application.

The bill received royal assent at the National Assembly today.

Ollivier said so far, the province hasn't offered any guidance as to how it's to be enforced.

Many organizations have concerns

It's not just the city of Montreal that's wondering.

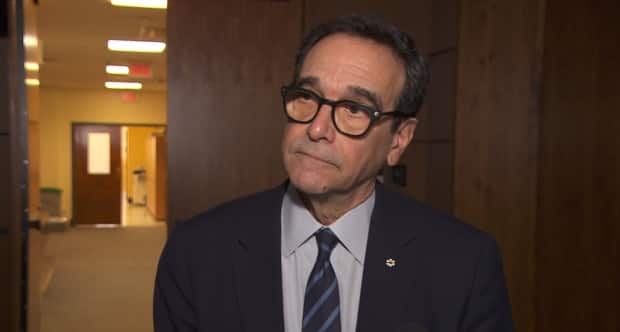

"Are they going to issue government ID to people certifying that you're entitled to service in English? I have no idea how they're going to make that work," Eric Maldoff, chair of the Coalition for Quality Health and Social Services and a longtime advocate for anglophone rights, said in an interview with CBC.

"Maybe they're contemplating that people are going to be cross-examined on arrival, and then the bureaucrat will make a determination as to whether they want to serve in another language," Maldoff said.

Several other organizations raised questions and concerns about how the law would be enforced during committee hearings at the National Assembly in January.

"Everybody's scratching their heads about this. And it poses a serious risk for the people who are running these institutions or working in them," Maldoff said.

In a written submission to the committee, the Quebec Union of Municipalities said enforcing the new law would pose "several issues" for its members, "in particular when the health and safety of the population are at stake."

"Municipalities should therefore have some flexibility to determine the situations in which they can communicate in a language other than French and which take into account the demographic profile of their population," the union said.

The Quebec Human Rights Commission also pointed out in its submission that determining who's a historic anglophone or how long a new immigrant has been in Quebec will pose "obvious practical difficulties" when enforcing the law.

The Round Table of Organizations Serving Refugees and Immigrants, which represents more than 150 groups in Quebec, noted in its written submission that a lack of precision in the legislation could pose particular problems for immigrants.

"Nowhere does the law mention the definition of 'immigrant,'" the group noted.

The round table said it's not clear if the limitation to a period of six months to receive government services in a language other than in French applies just to permanent residents, or also to temporary foreign workers, and people with precarious or no immigration status who may already have very limited access to government services.

Bill 96 is a sweeping piece of legislation that covers almost all government departments, municipalities and Crown corporations.

So this will come up a lot: when people are getting a new driver's license, asking questions about their hydro bill, applying for parental leave benefits, talking with their child's teacher — what are government employees supposed to do in all those situations if they're asked to speak English?

Details still being worked out

The short answer is that the province doesn't know how the law will be enforced yet.

Élisabeth Gosselin-Bienvenue, a spokesperson for the minister responsible for the French language, Simon Jolin-Barrette, told CBC in an email that Bill 96 won't start being applied for another year.

Over the next six months, the province will set up a new French language ministry, and that ministry will come up with a provincial linguistic policy for the entire public service and all municipalities and government organizations.

Those organizations will then have three months to submit their own plans for applying the policy to the ministry.

The ministry will then have three months to review, revise and approve those plans.

Finally, on or around June 1 next year, the law will start being enforced.

Confusion or misinformation?

But the lack of precise information now is already causing problems for the government.

After some high profile national and international news coverage about the new law last week, Jolin-Barrette suggested that "misinformation" about the law was being circulated.

That prompted the government to take out full-page ads in English newspapers yesterday and in French newspapers today in an attempt to clarify misconceptions about the law.

But Eric Maldoff believes the government has been deliberately vague about precisely how the law will work.

"I think the way the government's hoping this law will be enforced is to create enough confusion and enough discretion in the hands of the language police that people are not going to be certain of what they can do," Maldoff said.

"Therefore, they're going to refrain from serving in another language to avoid getting in trouble," he said.

Maldoff noted that under the new law anyone can file a complaint with the Office québécois de la langue française (OQLF) if they believe a service has been improperly provided in a language other than French.

"You're going to have people who work in the system who are of goodwill, and they're going to be looking over their shoulder as to whether somebody overheard them speaking in English or Greek or Italian or whatever it is," Maldoff said.

"All of this is going to lead to a lot of uncertainty in the minds of people who want to provide the services they're supposed to — a lot of nervousness, second guessing, hesitation," Maldoff said.

Jolin-Barrette's spokesperson, Élisabeth Gosselin-Bienvenue, said that's not true.

"Clear guidelines will be established based on the realities and services offered by the various departments," she said.